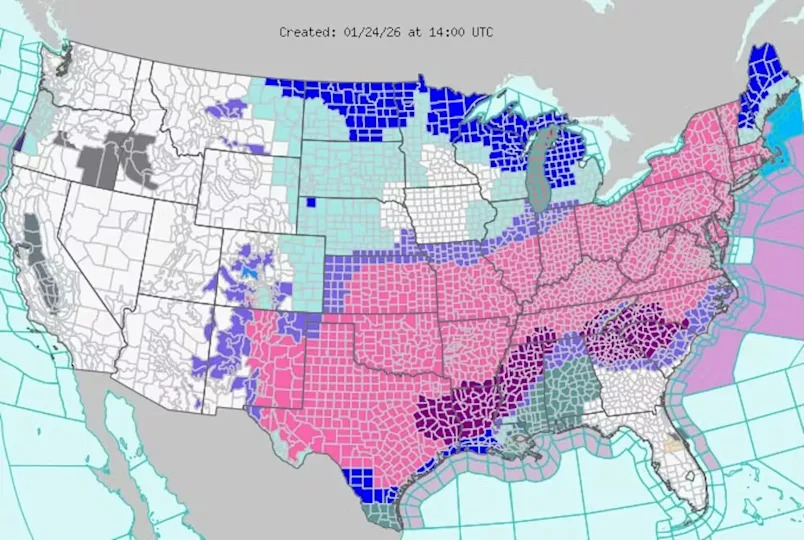

The late‑January 2026 storm — spanning New Mexico to New England — combined Arctic cold, a deep southward jet‑stream dip and abundant Gulf moisture to produce widespread freezing rain, sleet and heavy snow. The event was amplified by interactions with the stratospheric polar vortex (roughly 7–30 miles up), which helped transfer wave energy down to the surface. Climate change complicates the picture: more atmospheric moisture and Arctic warming can increase extreme storm intensity even as average snowfall trends decline. Continued federal support for observational and modeling centers like NCAR is vital to improve forecasts.

How the Stratospheric Polar Vortex Helped Fuel the Late‑January 2026 Storm

In late January 2026 a powerful winter storm swept from New Mexico to New England, bringing crippling freezing rain, sleet and heavy snow. Hundreds of thousands in the South lost power as ice snapped tree limbs and downed lines; parts of the Midwest and Northeast saw more than a foot of snow and prolonged bitter cold.

What Came Together to Produce the Storm

Large winter storms require several ingredients to align: sharp temperature contrasts near the surface, a southward dip in the jet stream that steers and amplifies systems, and an ample moisture source. In this event a strong Arctic air mass collided with unusually warm southern air, while disturbances in the jet stream combined to promote lift and heavy precipitation. The storm also tapped abundant moisture from a very warm Gulf of Mexico, fueling intense freezing rain, sleet and heavy snow.

Why the Stratosphere Matters

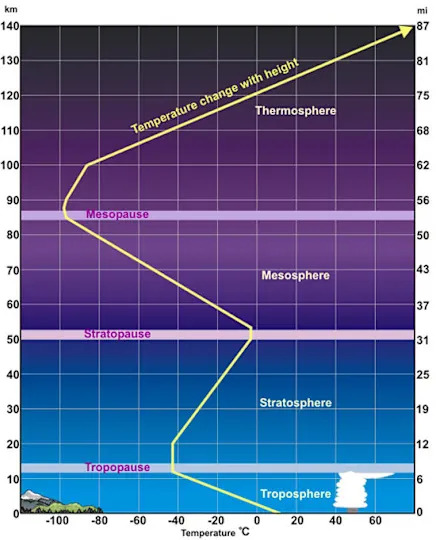

The fastest winds of the jet stream occur near the top of the troposphere — the lowest atmospheric layer where everyday weather occurs — which ends roughly 7 miles above the surface. Above it lies the stratosphere (about 7–30 miles up). Although the stratosphere sits well above surface weather, it interacts with the troposphere through atmospheric waves that propagate vertically. These waves can amplify or redirect jet‑stream patterns and influence surface weather days to weeks later.

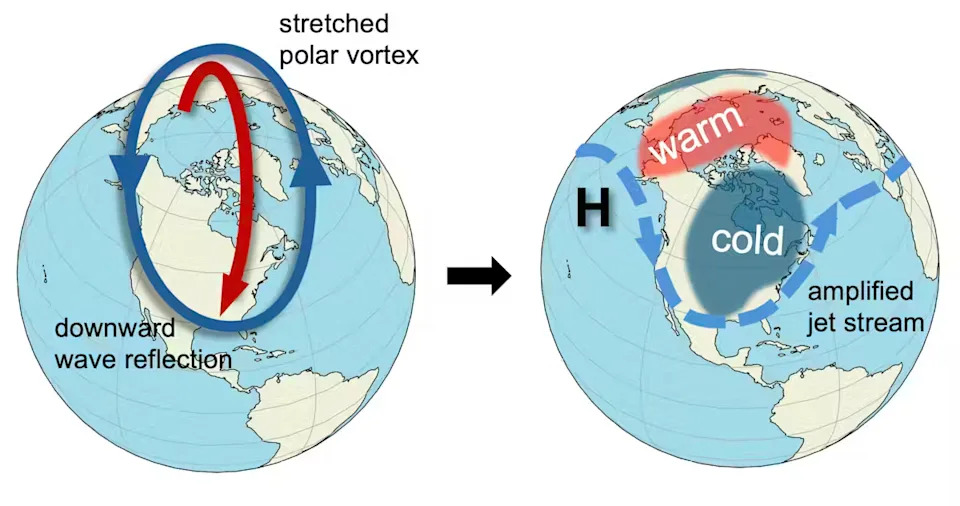

When people say "polar vortex" they may mean two different circulations: a tropospheric vortex closer to the surface, and a stratospheric polar vortex much higher up. The Northern Hemisphere's stratospheric polar vortex is a fast‑moving band of air encircling the pole. If that vortex stretches or shifts southward, it can enhance the vertical coupling between the stratosphere and troposphere, allowing wave energy to propagate downward and intensify surface cold and storminess.

The Late‑January Configuration

Forecasts for the January event showed a southward extension of the stratospheric polar vortex overlapping a strong southerly dip in the jet stream over the United States. Large jet‑stream swings carry the most energy; under the right conditions that energy can reflect off the polar vortex and return to the troposphere. That process amplified north–south oscillations of the jet stream across North America and contributed to the severe winter weather experienced across the central and eastern U.S.

How Climate Change Interacts With These Dynamics

Earth is unequivocally warming as human‑caused greenhouse gas emissions trap more heat. That warming has several, sometimes opposing, effects on winter storms:

- Arctic Amplification: Faster warming in the Arctic appears linked to more frequent disruptions of the stratospheric polar vortex, which can increase the risk of abrupt cold spells at midlatitudes.

- More Moisture: Warmer oceans and atmosphere increase evaporation and moisture content, supplying more water vapor to storms. When this moisture condenses it releases latent heat, adding energy to storms.

- Reduced Temperature Contrast: At the same time, overall warming can reduce the temperature gradients that drive some storms, potentially weakening average storm strength.

Because of these competing influences, changes to average storm behavior are complex. However, evidence suggests that the most intense winter storms may become as intense or more intense even as average snowfall declines in many regions. Warming also increases the likelihood that precipitation that formerly fell as snow will instead become sleet or freezing rain, altering hazards and impacts.

Why Observations and Models Matter

Improving forecasts requires high‑quality observations and models. Much of the foundational data, instruments and modeling tools come from federal research centers and government laboratories, such as the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). Proposed funding cuts or reduced support for such institutions would threaten the data and modeling capacity essential to forecasting and understanding extreme events.

Bottom line: The late‑January 2026 storm was the result of a rare alignment of Arctic cold, a southerly jet‑stream dip, strong vertical coupling with the stratospheric polar vortex, and abundant Gulf moisture. Climate change can both amplify and alter these dynamics — increasing moisture and disrupting high‑altitude circulation — so robust observations and modeling are critical to prepare for future extremes.

Help us improve.