Electrides are materials in which electrons occupy pockets between atoms rather than being bound to nuclei. Under extreme inner-core pressures iron may form an electride that sequesters light elements, offering a potential explanation for Earth’s depletion of hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and noble gases. At the same time, ambient-condition electrides such as mayenite are already lowering energy costs for ammonia production, and new room-temperature electrides promise greener routes to pharmaceuticals. Major challenges remain in predicting, stabilizing and scaling useful electrides.

Electrides: Hidden Electrons, Earth’s Missing Light Elements, and Greener Chemistry

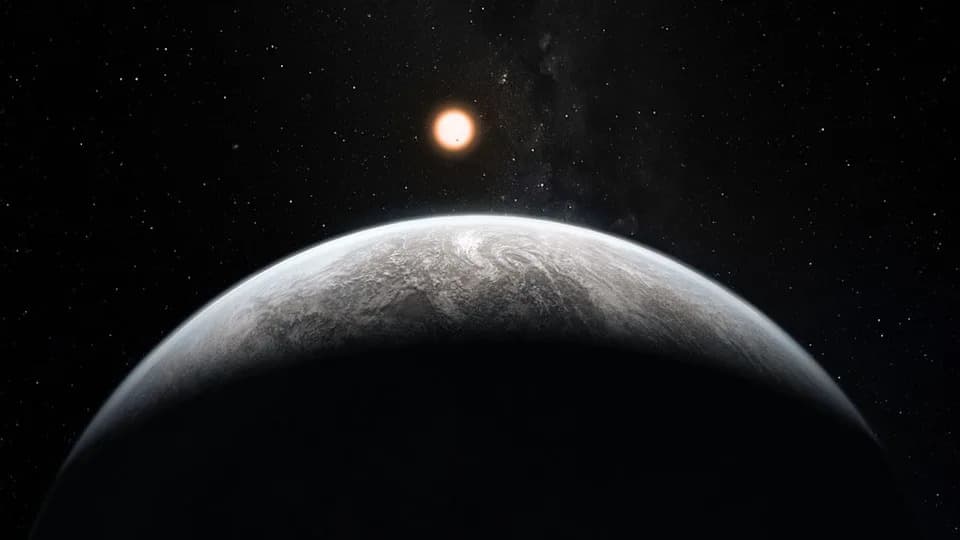

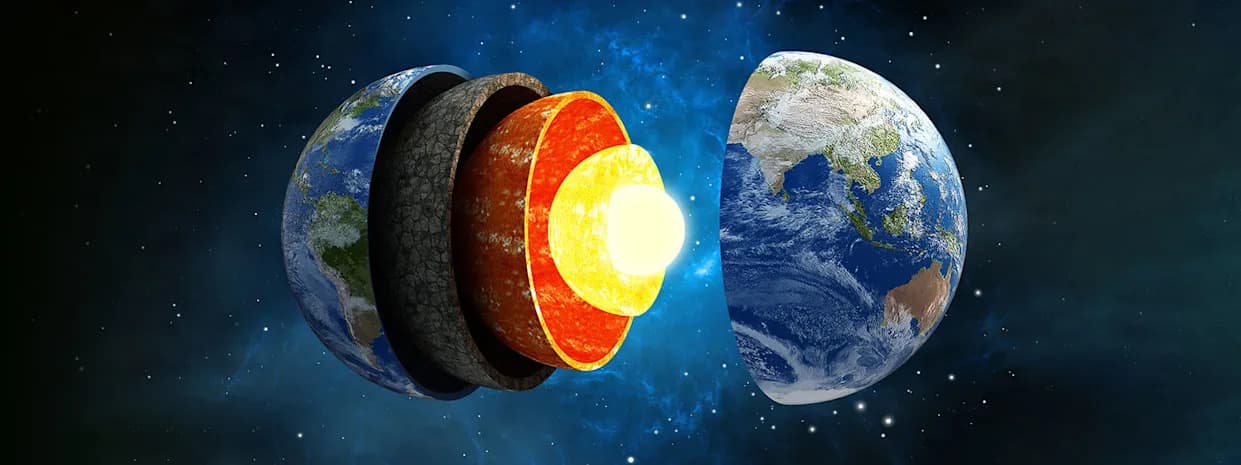

For nearly a century scientists have puzzled over a striking imbalance: compared with the Sun and some meteorites, Earth is dramatically depleted in light elements such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and sulfur, and in noble gases like helium. A recent hypothesis proposes that many of these elements may be trapped deep in Earth’s solid inner core because iron under extreme pressure can form an exotic electronic state called an electride.

What Are Electrides?

Electrides are solids in which some electrons do not belong to any single atom but occupy discrete pockets in the lattice known as non-nuclear attractors. Unlike the delocalized ‘‘sea of electrons’’ in ordinary metals, these trapped electrons are localized in interstitial sites and can act as highly reactive, easily donated electron sources. That unique arrangement gives electrides unusual electrical, chemical and catalytic properties.

Could Electrides Hide Earth’s Light Elements?

Under the enormous pressures of Earth’s inner core (roughly 360 gigapascals, about 3.6 million times atmospheric pressure), simulations suggest iron’s electron structure could reorganize to create non-nuclear attractor sites that stabilize light elements. If hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and similar atoms are held in these interstitial sites, they could diffuse into the iron and explain why seismic data indicate the inner core is 5–8% less dense than a pure iron core would be. However, that interpretation is still debated: iron’s more tightly bound valence electrons make electride formation less straightforward than in alkali and alkaline-earth metals, and some researchers call the iron-electride idea controversial.

From High Pressure Labs to Room Temperature Materials

The first metal found to transform into an electride under extreme compression was sodium. At roughly 200 gigapascals sodium changes from a shiny, conducting metal into a transparent, glassy insulator — a surprising result confirmed experimentally when researchers used diamond anvil cells and X-ray diffraction to map electron density and observed electrons in interstitial sites.

At ambient conditions, several electrides have since been discovered. A notable example is mayenite, a calcium aluminate oxide whose crystal cages can host trapped electrons. When electrons occupy those cages, mayenite becomes conductive (though far less so than common metals) and an effective electron donor, making it a promising catalyst support for difficult reactions.

Industrial And Scientific Applications

Mayenite-based catalysts have been developed to lower the energy needed to synthesize ammonia, the backbone of modern fertilizers. By supporting ruthenium nanoparticles, mayenite donates electrons that facilitate nitrogen and hydrogen bond breaking, enabling ammonia synthesis at lower temperatures (about 300–400°C) and pressures (50–80 atm) than conventional Haber-Bosch plants. Commercial efforts led by Tsubame BHB grew from a pilot plant in 2019 to larger operations and plans for a 20,000-ton-per-year green ammonia plant in Brazil that could avoid an estimated ~11,000 tons of CO2 annually.

Researchers are also uncovering room-temperature electrides for organic synthesis. In 2024 a calcium coordination complex formed a nonconducting electride that can activate unreactive bonds and perform reactions otherwise dependent on costly catalysts such as palladium. That material is air- and water-sensitive at present, but it demonstrates the potential for electrides in pharmaceutical and fine-chemical manufacture.

Challenges And The Road Ahead

Key hurdles remain. Predicting which materials become electrides is difficult — there is no universal theory yet. Experimental confirmations are still relatively few, and many promising electrides are sensitive to air or moisture, limiting industrial use. To accelerate discovery, researchers are combining high-resolution quantum simulations with machine learning to screen tens of thousands of compounds and prioritize candidates for laboratory validation.

"Electrides occupy an unusual corner of chemistry — they challenge intuition and reward careful computation and experiment," says computational materials scientist Lee Burton. "The potential is enormous if we can find stable, scalable examples."

Why It Matters

Electrides sit at the intersection of fundamental geoscience and practical chemistry: they offer a plausible explanation for a longstanding planetary puzzle while also enabling greener, lower-energy chemical processes. Continued collaboration among theorists, experimentalists and industry will determine which electride concepts remain scientific curiosities and which become transformative technologies.

Help us improve.