The Monash University team isolated an enzyme called Huc that strips trace hydrogen from the atmosphere and converts it into an electric current, a discovery reported in Nature. Purified Huc is unusually stable — surviving freezing and brief heating to 80°C — and the producing bacteria can be cultured at scale, suggesting potential for production. The findings are promising but early-stage: researchers must scale production, quantify real-world power output, and integrate Huc into practical devices.

Scientists Harness an Enzyme That Turns Trace Hydrogen in Air Into Electricity

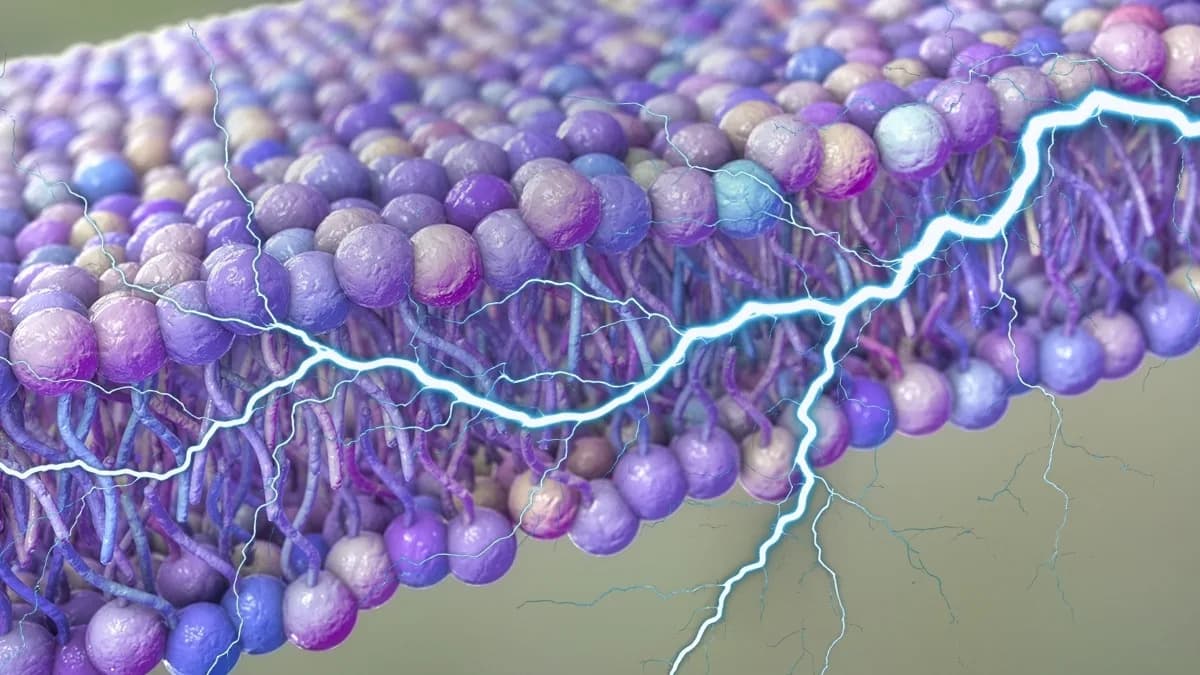

Researchers at Monash University have isolated a bacterial enzyme that extracts tiny amounts of hydrogen from the atmosphere and converts it into an electric current — a surprising discovery that could point to new low-impact ways to generate electricity.

What the Team Discovered

The team led by Dr. Rhys Grinter, Ph.D. student Ashleigh Kropp and Professor Chris Greening at the Monash University Biomedicine Discovery Institute identified and characterized a hydrogen-consuming enzyme called Huc, produced by the soil bacterium Mycobacterium smegmatis. Their results were published in the journal Nature.

Rather than a magic trick, the finding rests on microbial biochemistry: Huc scavenges trace atmospheric hydrogen (H2) and can transfer the resulting electrons to produce an electrical current. Many bacteria are known to exploit atmospheric hydrogen to survive in nutrient-poor or extreme environments, and this work reveals the molecular machinery behind that ability.

"We've known for some time that bacteria can use the trace hydrogen in the air as a source of energy to help them grow and survive, including in Antarctic soils, volcanic craters, and the deep ocean," Professor Greening said. "But we didn't know how they did this until now."

Stability and Scalability

Kropp's experiments show that purified Huc is unusually robust: it remains active after long-term storage, freezing and even brief exposure to high temperatures (reported activity after heating to 80°C / 176°F). The bacteria that produce Huc can be cultured at scale, which raises the possibility of producing the enzyme in useful quantities.

Despite these promising features, the researchers emphasize that the work is early-stage. Key challenges remain, including how efficiently Huc can generate power at practical scales, how to integrate the enzyme into durable devices, and the economics of large-scale production.

Potential And Perspective

If those hurdles can be overcome, Huc-based systems could complement existing clean-energy technologies by providing a low-footprint, continuous source of small-scale power — for sensors, off-grid devices, or as components in hybrid systems. As Dr. Grinter noted, "When we can produce Huc on a large scale, the sky is quite literally the limit for using it to produce clean energy."

Takeaway: This discovery reveals a novel biochemical route for converting atmospheric hydrogen into electricity and opens a path for further research into enzyme-based energy technologies, while underscoring that substantial engineering work is still needed before practical application.

Help us improve.