The universe hosts explosions across vast scales, from solar flares and white-dwarf novae to supernovae, magnetar flares, gamma-ray bursts, and mergers of supermassive black holes. Solar storms can disrupt satellites and power grids, while supernovae and GRBs pose greater hazards if they occur nearby. The most energetic events — black-hole mergers — convert a significant fraction of mass into energy emitted mainly as gravitational waves. Despite their destructiveness, these explosions create heavy elements and trigger new star formation.

The Biggest Bangs in the Cosmos: From Solar Flares to Colliding Supermassive Black Holes

The night sky looks peaceful, but it hides a theater of violent events whose energies can dwarf anything humans can imagine. From local solar storms to titanic black-hole mergers, cosmic explosions span an enormous range of scale, impact, and consequence. This article tours those explosions, explains how dangerous they can be, and why they are also crucial for making planets and life.

“Don’t panic.” — Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Solar Storms: Our Most Familiar Explosions

Closest to home are eruptions from the Sun. Solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) release magnetic energy stored in the Sun’s atmosphere. Both launch high-energy particles and electromagnetic radiation that can disturb Earth’s magnetosphere, damage satellites, and induce power-grid failures — and they produce spectacular auroras.

One example: during a few hours in 2003, the most powerful solar flare directly measured emitted roughly the same energy the Sun produces in about one-fifth of a second. That is equivalent to detonating about 17 billion one-megaton nuclear bombs at once. Such events are rare, and their effects on Earth depend on direction and distance, but they are a real hazard to modern technology.

White Dwarfs and Novae

A white dwarf is the dense remnant of a Sun-like star. In a binary system it can siphon material from a companion until surface layers ignite in runaway fusion, producing a nova. A single nova can emit about as much energy as the Sun does over centuries; some systems produce recurrent novae, erupting repeatedly over long timescales.

Supernovae: Stellar Cataclysms

When massive stars end their lives, their cores collapse and outer layers are explosively expelled in a supernova. In an instant, enormous masses of material are flung outward at a significant fraction of the speed of light. Supernovae release millions of times the energy of a nova and can briefly outshine entire galaxies.

Thermonuclear supernovae can also occur when a white dwarf accumulates enough mass to trigger a destructive explosion. Estimates suggest a supernova within roughly 160 light-years could pose serious risks to Earth’s atmosphere and biosphere. Geological traces of radioisotopes in deep-sea sediments show that Earth has been exposed to material from nearby supernovae millions of years ago — not extinction-level in that instance, but a sobering reminder of cosmic reach.

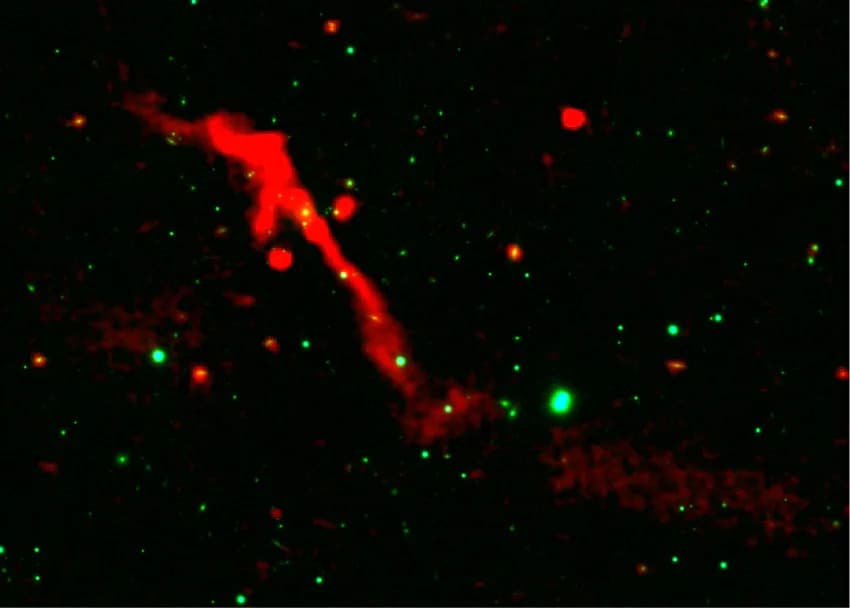

Magnetars: Starquakes and Giant Flares

Magnetars are neutron stars with extraordinarily strong magnetic fields. Their crusts can shift in starquakes that unleash intense bursts of gamma rays and X-rays. In December 2004, a giant flare from the magnetar SGR 1806−20 — about 50,000 light-years away — briefly altered Earth’s ionosphere and perturbed the magnetic field. Thankfully, that event was far enough away to be only a remote disturbance.

Black Holes and Gamma-Ray Bursts

Black holes are associated with some of the universe’s most extreme transients. When some massive stars collapse to form black holes, they can launch tightly collimated jets that produce gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). Because the energy is concentrated into narrow beams, GRBs can be dangerous from much greater distances than isotropic explosions — a burst within ~6,000 light-years could threaten Earth’s atmosphere. GRB 080319B, for example, occurred about 7.5 billion light-years away and was briefly visible to the naked eye.

Stars that wander too close to a supermassive black hole can be tidally shredded in tidal disruption events, releasing energies comparable to supernovae. These flares are commonly observed in distant galaxies.

The Biggest Bangs: Merging Supermassive Black Holes

When galaxies merge, their central supermassive black holes can eventually collide. In such mergers, roughly 10% of the system’s mass can be converted into energy and carried away as gravitational waves — an amount of energy that defies easy intuition. For instance, the coalescence of two billion-solar-mass black holes can release an energy comparable to what the Sun would emit over ~3 × 10^21 years. Most of this energy is emitted as gravitational waves, not light, and these mergers are rare and typically occur billions of light-years away.

Why These Explosions Matter

Despite their destructive power, cosmic explosions are essential to cosmic evolution. Supernovae and related eruptions forge and disperse heavy elements such as iron and calcium, ingredients of planets and life. Shock waves and energetic outflows compress interstellar gas and can trigger new star formation. In that sense, violent endings often seed new beginnings.

Takeaway: Cosmic explosions range from locally disruptive solar storms to cataclysmic black-hole mergers. They can threaten technology and, in rare close cases, life on Earth — yet they are also the engines that build the chemical elements and structures that make planets and life possible.

Help us improve.