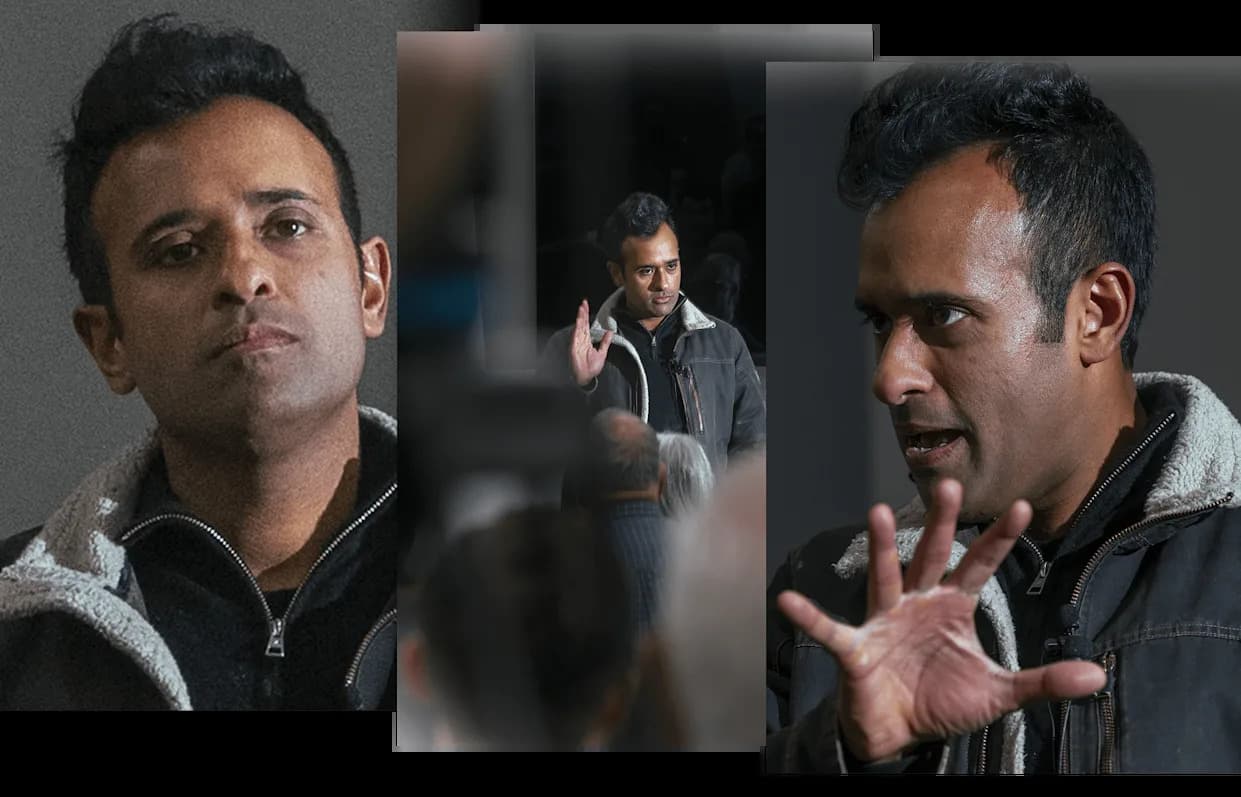

The author, a volunteer legal observer in Minneapolis, describes being detained by officers believed to be ICE for eight hours after legally filming their activity on Jan. 11. Arrested three minutes and thirty seconds after arriving at the scene — four days after neighbor Renee Good’s death — the author reports being held at the Whipple Federal Building, where basic needs were ignored and other detainees appeared distressed. Attorney Emanuel Williams warns that access to counsel has become inconsistent, and volunteers believe detentions are being used to deter documentation. Despite intimidation, the community’s observer network continues to record and adapt.

I Was Detained Eight Hours for Legally Filming ICE — Here's What I Saw

Masked, tactical-clad officers surrounded the car where my friend Patty and I were sitting. I kept thinking about my neighbor Renee Good’s last words — “I’m not mad at you.” The men, who never identified themselves but whom I believed to be Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), banged on our windows and filmed us. They then pepper-sprayed the car’s intake vent; the message was clear — they were hostile.

“You’re under arrest!” the agents shouted. I raised my hands and waited for instructions that never came. Instead they shattered our windows, dragged me out, handcuffed me roughly and shoved me into the back of an unmarked Subaru.

I had volunteered with a neighborhood group organized to observe and report ICE activity after Operation Metro Surge began in Minnesota weeks earlier. The effort intensified after Good’s killing. In community Signal chats, suspected ICE sightings are posted, license plates are checked against a public spreadsheet, and confirmed vehicles draw volunteers who film and warn the neighborhood with car horns and whistles. Recording on public streets is a legally protected action.

Most observer shifts are routine. Volunteers circulate familiar streets, watching restaurants, community centers and other public places where Minneapolis residents gather. Dispatchers coordinate where to go; it’s common to hear someone ask listeners to leave the call if you are not actively commuting so space on the Signal channel remains available.

But commuting can be terrifying. A circulated video shows an officer taunting a legal observer two days after Good’s death: “Have y’all not learned?” When the observer replies, “What’s our lesson here?,” the agent lunges for her phone. Officers have also followed commuters to their homes, prompting frequent messages in chats such as, “He’s following me to my house.” Once, I advised a frightened woman to meet me at a gas station because an ICE vehicle was idling outside her home.

My detention began on Jan. 11. Someone in our neighborhood chat reported that ICE vehicles were pepper-spraying an observer; Patty and I, nearby, drove to the scene. This location was six minutes from where Renee Good had been killed four days earlier. Within moments of our arrival the agents pepper-sprayed the interior of our car and pulled us out. By the time they shoved me into the unmarked SUV, three minutes and thirty seconds had passed. We had not blocked their vehicles or done anything beyond routine observing and filming, and we did not know why we were being detained.

Separated from me, Patty endured humiliation in custody: officers insulted her appearance, photographed her, and referred to Renee Good with derogatory language. Both of us were transported to the Whipple Federal Building — the same facility three local lawmakers had been denied access to the day before when they tried to check conditions inside. As I was processed, shackled and led into a holding cell, I wondered whether I would be able to report what I saw there.

My cell was a bare yellow room. I tried to sleep but could hear screaming and crying deeper in the facility whenever I closed my eyes. Requests to use the bathroom or to have water were ignored until I pounded on the one-way glass and shouted at agents. When I was finally permitted to use the restroom, I glimpsed other detainees through observation windows: more than a dozen people packed into a holding cell, listless and withdrawn. One man pressed his face to the one-way glass as if seeking any connection.

Through another observation window I watched a woman use the toilet, draped in a modesty garment — yet three agents stood nearby watching, making small talk and laughing while she cried. The scene was humiliating and dehumanizing.

I was fortunate to be released after eight hours in custody and without charges. My family had contacted a lawyer, Emanuel Williams, whose help mattered. Williams told me procedures at Whipple are changing and becoming more hostile toward people detained — including U.S. citizens — with access to counsel sometimes depending on who is on duty. He described occasions when officers at the guard post said the building was closed and when a staff member approached his vehicle carrying pepper spray.

A video of my cellmate Dennis’s arrest shows two agents forcing his body forward into an unmarked van while a third fumbles for pepper spray on his tactical vest. One agent brings the spray inches from Dennis’s eye and asks, “Do you want me to spray you?” Another agent intervenes and scolds him. Dennis later laughed and told me he had said, “Go ahead.”

Patty and I are not alone. Since that day we have met four other volunteers who say they were detained while trying to alert people to ICE presence and to document officers. I was never charged; I now believe our detention was intended to prevent documentation of ICE activities. My arresting agent took my whistle — after my release I bought a pack of 24 to replace it.

Why This Matters

Minneapolis has built a resilient observer network that documents enforcement activity and alerts communities. In response, ICE appears to be shifting some operations to surrounding areas with fewer organized observers. Officers clearly prefer to work out of sight — which makes public documentation and organized observing more important than ever.

Note: All events described reflect the author’s direct experience and the accounts of volunteers and counsel involved in the case.

Help us improve.