LifeTracer is a machine-learning framework that classifies complex organic mixtures as likely abiotic or biotic by analyzing whole-pattern chemical fingerprints rather than searching for single molecules. Using extracts from eight carbon-rich meteorites and 10 terrestrial soil and sediment samples, the model reliably distinguished meteorite-derived chemistry from degraded biological material even with only 18 training examples. The method highlights distributional markers such as volatility patterns and the presence of compounds like 1,2,4-trithiolane, but it is not a universal detector of life. Instead, LifeTracer provides a practical, quantitative foundation for interpreting returned samples from Mars, its moons, Europa, and Enceladus.

Can We Detect Life Without Its Chemistry? A Machine Learning Method Clarifies the Search

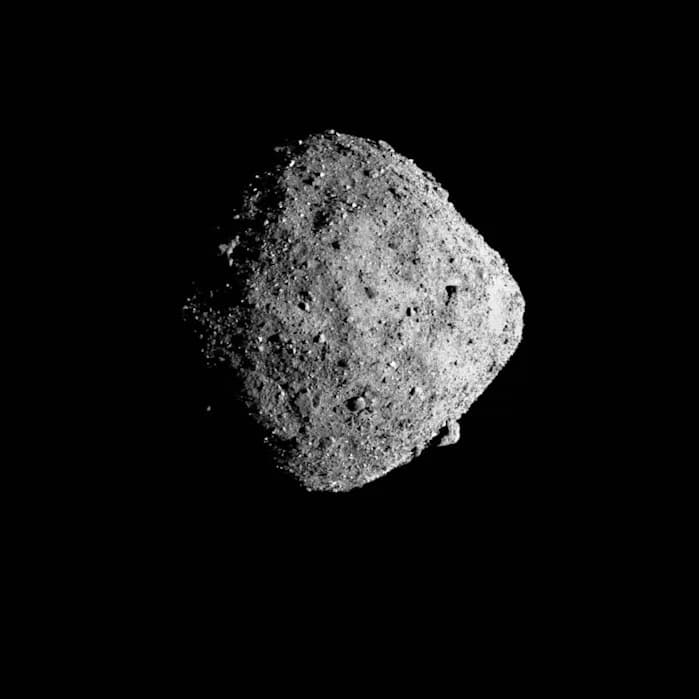

When NASA opened the OSIRIS-REx sample-return capsule in late 2023, scientists discovered an unexpectedly rich mix of organic molecules in material from the asteroid Bennu. The sample contained all five nucleobases used in DNA and RNA, 14 of the 20 amino acids that compose proteins, and a wide array of other carbon- and hydrogen-based organics. Those findings reinforce long-standing ideas that early asteroids could have delivered life’s raw ingredients to Earth — yet they also complicate the question of how to recognize life beyond our planet.

Why Bennu Raises the Alarm

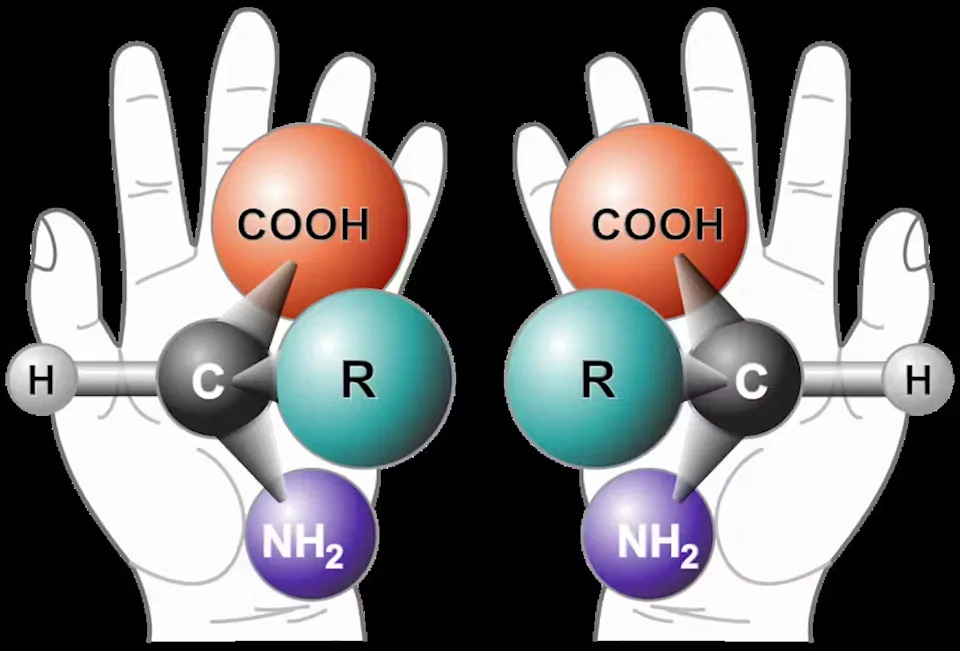

One striking feature of the Bennu amino acids was that they were nearly racemic: an almost equal mix of left- and right-handed (chiral) forms. Terrestrial biology overwhelmingly uses left-handed amino acids, so a strong left-handed excess on Bennu would have suggested that Earth inherited molecular handedness from space. Instead, the balanced mix points to the likelihood that biological chirality emerged on Earth after those ingredients arrived. This example shows how lifelike chemistry can exist without biology, which makes distinguishing biology from complex abiotic chemistry a harder problem.

From Molecules to Patterns: The LifeTracer Idea

My colleagues and I tackled this problem by developing LifeTracer, a framework that uses machine learning to assess whether an entire chemical mixture looks more like the output of living systems or the result of abiotic processes. Rather than searching for a single telltale molecule or familiar biochemical structure, LifeTracer evaluates the full pattern of chemical fingerprints preserved in a sample.

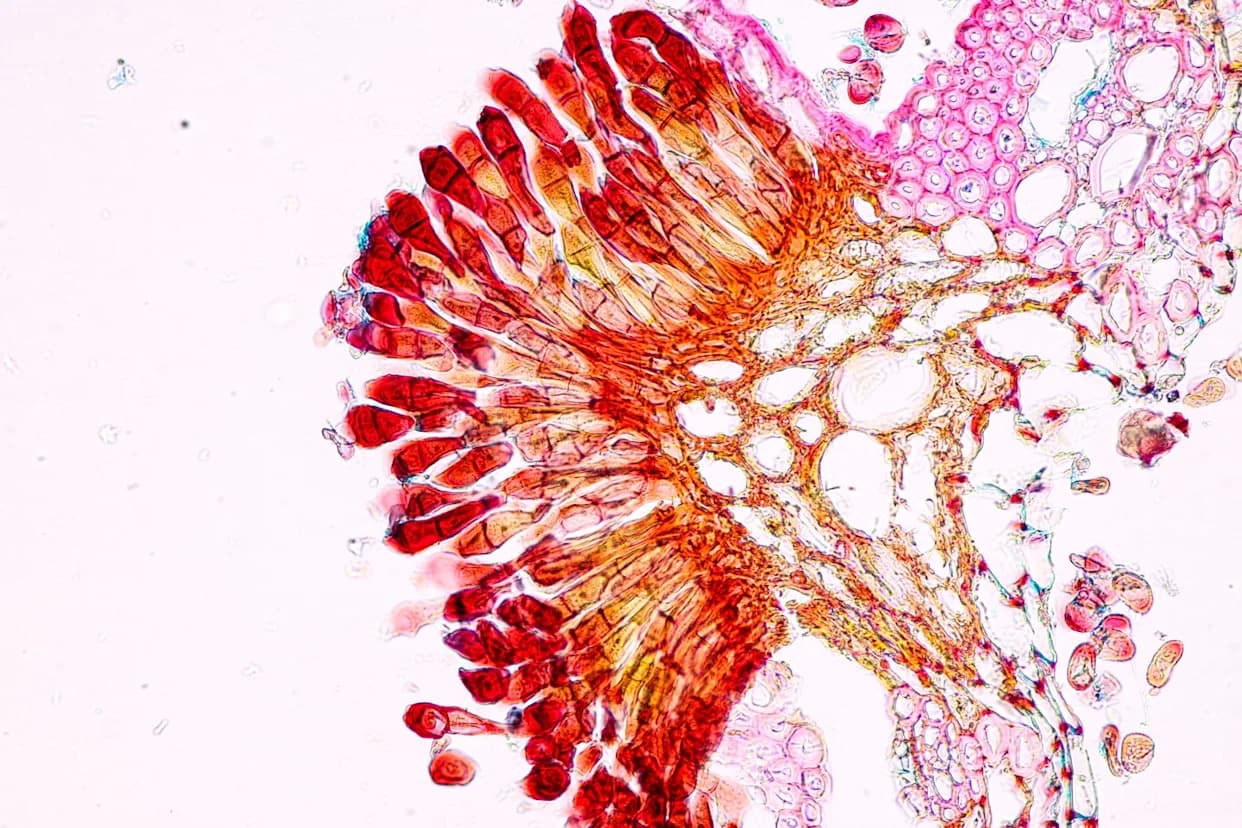

Underlying this approach is a simple premise: life produces molecules with purpose, shaped by metabolism and evolution. Cells must store energy, build membranes, and encode information, producing molecular distributions that reflect those functions. Abiotic chemistry, even when abundant and organized, follows different generative rules because it is not driven by selection or metabolism.

How the Study Worked

We assembled a dataset deliberately placed at the interface between life and nonlife. The collection included organics extracted from eight carbon-rich meteorites that preserve early Solar System abiotic chemistry, and organics from 10 terrestrial soils and sediments that contain degraded products of biological activity. Each sample yielded tens of thousands of organic compounds, many at low abundance and many without fully resolved structures.

At NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, samples were ground, solvent-extracted, and separated by two chromatography columns. The resulting extracts were analyzed with electron impact fragmentation, producing mass fragments traditionally used by chemists to reconstruct molecular structures. Because fully reconstructing tens of thousands of compounds per sample was impractical, LifeTracer works directly with the fragment data.

The fragments were characterized by mass and two additional chemical descriptors, then organized into a large matrix representing each sample's molecular fingerprint. We trained a supervised machine-learning classifier on these matrices to distinguish meteorite-derived (abiotic) samples from terrestrial (biotic) materials. Even with only 18 total examples, the classifier performed consistently well at separating abiotic and biotic origins.

Key insight: The classifier learned patterns in the distribution and types of fragments rather than relying on any single molecule. Meteorite samples tended to be richer in volatile compounds consistent with cold-space chemistry, while terrestrial samples contained molecular products indicative of biological processing.

What Markers Emerged

Rather than single universal biomarkers, LifeTracer identified contrasts across suites of molecules. For example, certain structural variants of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons appeared in both groups but differed in ways the model could detect. A sulfur-bearing compound, 1,2,4-trithiolane, stood out as a strong marker for abiotic meteorite samples in our dataset. More broadly, the model emphasized distributional features — abundance patterns, volatility, and structural fingerprints — that together discriminate abiotic from biotic origins.

Implications and Limits

LifeTracer is not a universal life detector. It offers a quantitative tool for interpreting complex organic mixtures and reducing false positives and negatives when familiar biomolecules appear in nonbiological contexts. The Bennu example underscores the main lesson: life-friendly chemistry can be widespread in the Solar System, but chemistry alone does not prove biology.

Future returned samples from Mars, the Martian moons, Europa, Enceladus, and other worlds will likely be mixtures of organics from multiple sources. By focusing on whole-pattern recognition rather than single-molecule assumptions, LifeTracer and related approaches can help scientists weigh whether a chemical landscape looks more like evolved biology or the product of geochemical processes.

To confidently distinguish life from lifelike chemistry, we will need better instruments and missions, and smarter computational methods to read the stories embedded in molecular collections. LifeTracer is a step toward those smarter reads.

Help us improve.