Acid mine drainage in Appalachia contaminates an estimated 13,700 miles (22,000 km) of streams and produces treatment sludge that can contain rare earth elements at concentrations comparable to mined ores. Researchers have demonstrated methods to extract these metals and return cleaner water, potentially turning pollution into a domestic source of critical minerals. Legal uncertainty about ownership of recovered minerals — with West Virginia providing clearer rights and Pennsylvania remaining silent — is a major barrier to investment. Clarifying ownership, funding pilots and creating incentives could scale recovery and deliver environmental and economic benefits to local communities.

Turning Orange Streams Into Strategic Supply: Recovering Rare Earths From Appalachian Mine Waste

Across Appalachia, rust-tinted streams trace the legacy of coal mining: abandoned workings release acidic, metal-laden water that stains rocks orange and chokes streambeds. Known as acid mine drainage (AMD), these discharges harm aquatic life, corrode infrastructure and can threaten drinking-water supplies for decades.

Why the Orange Water Matters

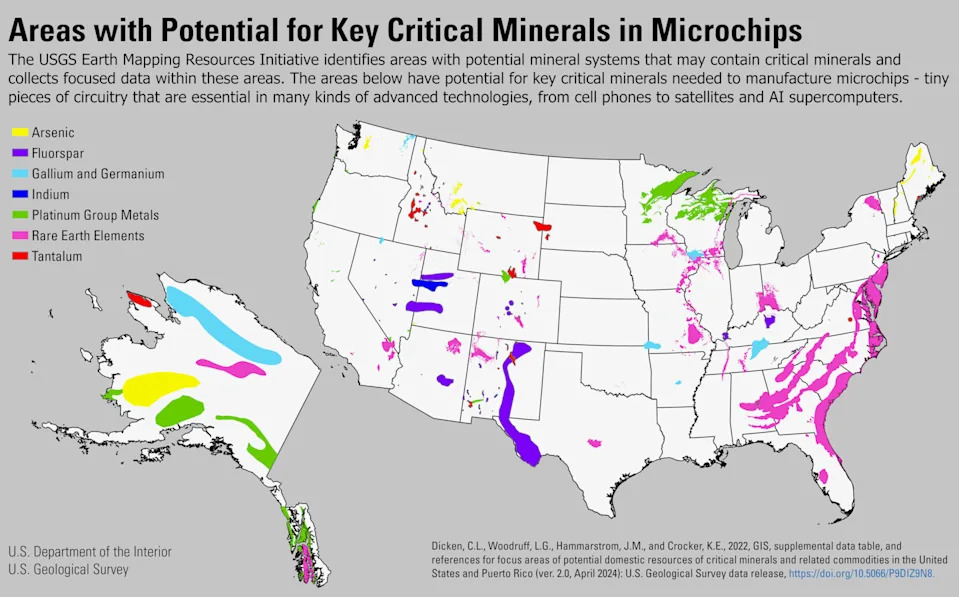

Hidden in that orange runoff are rare earth elements (REEs) — a group of 17 metals classified as critical minerals and essential to technologies from smartphones and wind turbines to military aircraft. Research shows some AMD and the treatment sludge it produces contain REE concentrations comparable to conventional mined ores.

How Acid Mine Drainage Forms And Is Treated

AMD forms when sulfide minerals such as pyrite are exposed to air and water, producing sulfuric acid that leaches metals (for example, iron, copper, lead and mercury) from surrounding rock. Iron precipitates give the water its characteristic orange color. Passive and active treatment systems neutralize acidity and precipitate dissolved metals into an orange sludge collected in treatment ponds.

Recovering Value While Cleaning Water

Scientists and engineers at institutions including West Virginia University and the National Energy Technology Laboratory have demonstrated methods to separate REEs from treatment sludge using water-safe chemistries. In test collections, researchers isolated REEs, returned cleaner water to streams and produced solids suitable for further processing. Because AMD has already mobilized the metals from rock, extraction can be simpler than conventional ore processing.

Scale, Benefits And Limits

Scaling recovery could lower cleanup costs, create local jobs and supplement domestic REE supplies needed for clean-energy and high-tech manufacturing. However, total volumes available in drainage sites are smaller than those produced by large conventional mines, and extraction technology and economics remain under development. Early studies suggest projects may be profitable, especially when multiple critical materials (for example, cobalt and manganese) are recovered alongside REEs.

Policy And Ownership: The Main Barrier

A major obstacle is legal ownership: traditional mining law focuses on subsurface minerals and does not clearly address materials recovered from surface waters or treatment sludges. Many nonprofit watershed groups operate treatment systems with public remediation funding; selling recovered minerals could create revenue for further cleanups but may conflict with grant terms or nonprofit rules.

State Policy Differences

Policy differences matter. In 2022, West Virginia enacted a law that grants ownership of recovered REEs to the extractor, providing clearer legal footing for recovery projects (though large-scale implementations are still pending). Pennsylvania’s Environmental Good Samaritan Act protects volunteers from liability when cleaning mine water but is silent on ownership of recovered materials. In a survey of treatment operators across both states, interest in REE recovery was roughly twice as high in West Virginia as in Pennsylvania — largely because of ownership certainty.

Geopolitical Context And Urgency

China controls roughly 70% of global REE production and nearly all refining capacity, a position it has used to influence prices and export policies in recent trade disputes (as recently as 2025). The United States currently imports about 80% of the REEs it consumes, which has made finding reliable domestic sources a national priority.

What’s Needed Next

To realize the promise of turning pollution into a strategic resource, policymakers, funders and communities should:

Clarify ownership of recovered materials; fund pilot projects and research to scale safe extraction methods; and design incentives and public–private partnerships that ensure local communities share the benefits of cleanup and development.

Recovering rare earths from acid mine drainage offers a twofold opportunity: to transform a long-standing environmental liability into domestic strategic materials, and to reduce the environmental costs of meeting rising demand for clean-energy technologies. With clearer rules, targeted investment and careful stewardship, Appalachian cleanup and clean-energy supply goals can advance together.

By Hélène Nguemgaing, University of Maryland, and Alan Collins, West Virginia University

Help us improve.