The undigested stomach tissue of a 14,000-year-old wolf pup found in Siberian permafrost allowed scientists to sequence the full genome of a woolly rhinoceros. Comparing this genome with two older permafrost genomes revealed no clear genetic decline before extinction, indicating the species maintained healthy genetic diversity until shortly before its disappearance. Researchers conclude the woolly rhino likely vanished rapidly due to post–ice-age warming rather than prolonged inbreeding or sustained hunting.

Wolf Pup’s Frozen Stomach Yields Full Genome of Ice-Age Woolly Rhinoceros

On the Siberian steppe about 14,000 years ago, a two-month-old wolf pup swallowed flesh from a woolly rhinoceros just before a collapse buried its den and killed the pup and its sister. Preserved in permafrost and discovered near Tumat, the mummified pup’s undigested stomach tissue has now enabled scientists to reconstruct the complete genome of one of the last woolly rhinoceroses.

The results, published in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution, represent the first time researchers have recovered and assembled a full genome from the stomach contents of another animal, says coauthor Camilo Chacón-Duque of the SciLifeLab Ancient DNA Unit at Uppsala University.

A rare window into extinction-era DNA

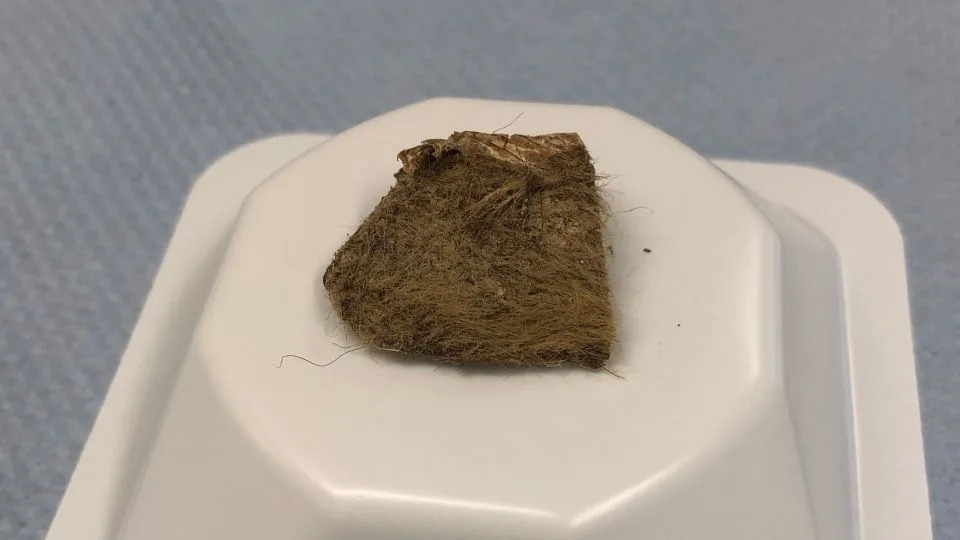

The specimen is unusually valuable because remains from the period when the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) disappeared are scarce. The wolf pup, found in 2011 and still covered in fur, yielded a small patch of remarkably preserved rhino tissue during autopsy. Radiocarbon and stratigraphic evidence date the material to roughly 14,000 years ago.

Hair on the rhino tissue appeared intact, indicating the pup had only just begun digesting its meal when the den collapsed. Earlier research concluded the pups likely died when a landslide buried their underground den; neither animal showed signs of external attack or injury.

How the genome was reconstructed

Sequencing the rhino genome was technically challenging because the stomach sample contained a mixture of ancient wolf and rhino DNA of similar age. That similarity prevented the team from using damage patterns to separate fragments. To assemble the rhino genome, researchers used the Sumatran rhinoceros—the woolly rhino’s closest living relative—as a reference.

Once assembled, the new genome was compared with two previously published woolly rhino genomes from Siberian permafrost, dated to about 18,000 and 49,000 years ago. Permafrost preserves DNA exceptionally well: researchers have recovered ancient molecules from high latitudes stretching back millions of years, making these mummies rich sources for genomic and ecological reconstruction.

Findings on population health and extinction

Contrary to expectations that late-surviving populations would show genetic deterioration, the analysis found no clear signal of rising inbreeding or accumulated harmful mutations as the species approached extinction. The authors conclude that woolly rhinoceroses retained stable genetic diversity and a sizeable, viable population until shortly before they disappeared.

Because the genomes show no long-term genetic decline, the researchers argue the species’ extinction was probably rapid and driven by environmental change—most likely the warming at the end of the last ice age—rather than by chronic inbreeding or sustained human hunting. Coauthor Love Dalén of the Centre for Palaeogenetics notes the species persisted for millennia after humans first reached northeastern Siberia, supporting a climate-driven scenario.

Broader significance

Experts not involved in the genomic work praised the study’s value. Nathan Wales, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of York who previously studied the wolf pups, called the sequencing “extremely valuable” for reconstructing the woolly rhinoceros’s evolutionary history. He also pointed out additional research opportunities: the pups’ stomachs contained plants, insects and a small bird (a wagtail), which could yield further ancient DNA insights into diet, microbiomes and ecosystem context.

Permafrost mummies, unlike isolated bones, preserve soft tissues and direct traces of life—dietary remains, gut microbiomes and the animals’ outer appearance—providing a vivid, multi-dimensional record of past ecosystems and the final chapters of extinct species.

Notes: The genomic analysis was led by teams at the Centre for Palaeogenetics and SciLifeLab. Earlier interpretations that the pups might have been early domesticated dogs were revised after a 2025 study found no evidence the animals had contact with humans.

Help us improve.