A study in Nature shows many river deltas are disappearing not only because of rising seas but because the land itself is subsiding — in some places as fast or faster than sea level rise. Researchers flag extreme sinking in Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta and identify primary causes including reduced sediment supply and widespread groundwater withdrawal. The findings heighten urgency for targeted restoration, especially after Louisiana canceled two major sediment-diversion projects; some regions may require relocation rather than repair.

River Deltas Are Vanishing — The Land Is Sinking Faster Than Many Realize

Great white egrets wade through wetlands near New Orleans as parts of the Mississippi River Delta continue to sink — a process driven by both natural subsidence and human activity that, in many places, matches or outpaces rising seas.

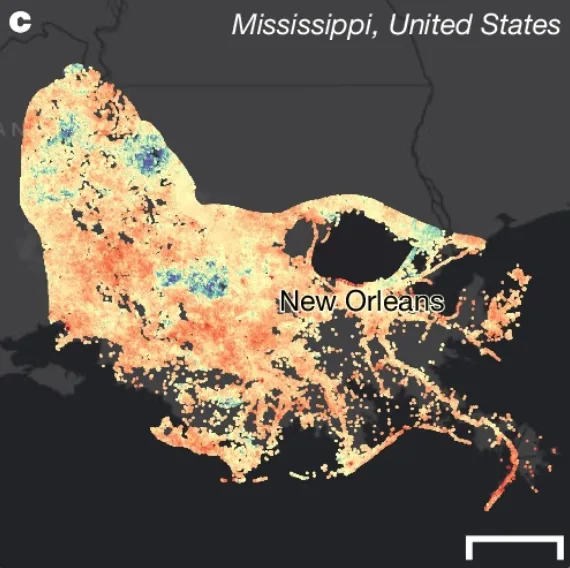

A new study published in Nature finds that many of the world’s river deltas are not only threatened by sea level rise but are also losing elevation as the ground itself subsides. The research identifies extreme rates of sinking in Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta and shows that subsidence is frequently overlooked when assessing coastal risk.

Why Deltas Are Sinking

Some subsidence is natural: river-borne sediment compresses soft, organic soils beneath deltas, causing gradual settling. But human activities can greatly accelerate that process. Engineers who alter river channels, and the extraction of groundwater, oil or gas can all increase the rate of sinking.

Leonard Ohenhen, lead author and professor at the University of California, Irvine, notes the global stakes: coastal zones account for under 1% of Earth’s land area, yet more than 600 million people live in those regions. Understanding whether land is sinking — and why — is critical to making responsible choices about restoration and relocation.

Key Drivers Identified

The study found that roughly 70% of the examined deltas have subsidence largely linked to groundwater withdrawal. In other systems — notably the Amazon and Mississippi deltas — the dominant problem is sediment starvation: rivers no longer deliver enough sediment to rebuild land lost to compaction and erosion.

“Relative sea level rise — the combination of ocean rise plus local land subsidence — is the metric that matters for communities and restoration planning,” said Alisha Renfro of the National Wildlife Federation.

Why Louisiana Is Particularly Vulnerable

In the Mississippi River Delta, average subsidence is about 3.3 millimeters per year, but some locations are sinking at nearly 3 centimeters per year — among the fastest rates recorded in the study. At the same time, sea levels along the U.S. Gulf Coast are rising at about 7 millimeters per year, placing parts of Louisiana at especially high risk. The combination of rapid subsidence and accelerating sea level rise has already prompted relocation of some communities.

Restoration options such as sediment diversions — large engineering projects designed to redirect river water and sediment into adjacent wetlands — were proposed to help rebuild land. Two such projects in Louisiana, Mid-Barataria and Mid-Breton, were canceled amid concerns about potential impacts on fisheries such as oysters and crabs, intensifying debate about trade-offs and urgency.

What This Means For Policy And Communities

By quantifying subsidence and distinguishing human from natural causes, the paper gives policymakers and restoration planners better tools to prioritize investments. Some areas may still be defendable with timely sediment restoration, while others may require managed retreat and community relocation planning.

James Karst of the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana says the research validates long-standing concerns about reduced sediment supply to the delta and underscores the need for immediate, pragmatic action.

With stakes this high — ecological, economic and human — the study urges decision-makers to act now to avoid irreversible land loss.

Help us improve.