Fires aboard spacecraft behave very differently from those on Earth: in microgravity, flames tend to form spherical balls that radiate heat in all directions. After the Apollo 1 cabin fire, oxygen levels in crewed vehicles were set to about 21%; NASA has since proposed raising levels to ~35% to cut vehicle mass, which increases fire risk. A Europe-backed team is studying ignition, spread and suppression using parabolic flights, sensors, acoustic tests, simulations and a planned rocket mission, backed by €14 million in funding.

When Fire Ignites in Space: Why Flames Become Spheres — And How Scientists Plan To Extinguish Them

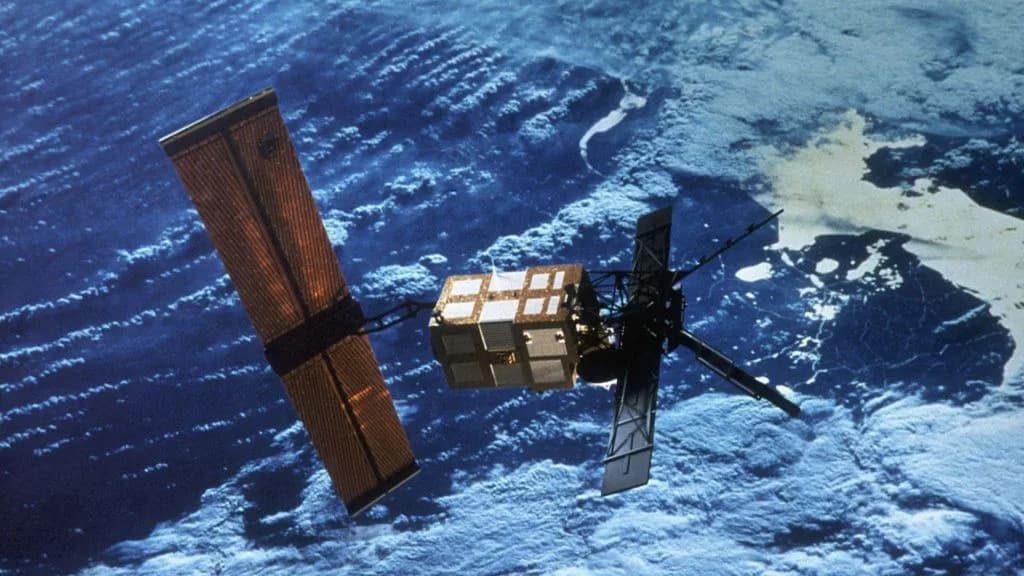

Fires that start inside spacecraft or space stations behave very differently from those on Earth. In the low-gravity, confined environment of a spacecraft, flames can form roughly spherical balls that radiate heat in all directions, complicating detection and suppression — a critical concern as humans plan missions to the Moon and Mars.

Why Fire Is Especially Dangerous in Space

The threat of cabin fire in crewed missions is not theoretical: days before the planned January 1967 launch of Apollo 1, a cabin blaze during a ground test killed the three crew members aboard. At the time, capsules were filled with pure oxygen at reduced pressure so astronauts could breathe more easily. As fire researcher Serge Bourbigot of France's Centrale Lille institute explains, "the more oxygen you have, the more it burns." After the Apollo 1 tragedy, oxygen levels in crewed spacecraft were set to about 21% — similar to Earth's atmosphere.

Recently, NASA recommended raising oxygen concentrations in some new spacecraft and stations to around 35% to allow lower internal pressure and lighter structures, reducing launch mass and cost. Higher oxygen levels, however, increase flammability and elevate the risks associated with any ignition event.

A Spherical Flame

On Earth, hot gases from a candle rise because warm air is less dense than surrounding air, producing a familiar upward plume. In microgravity or weightless conditions, buoyant flow is absent: heated gases do not rise. Instead of a teardrop-shaped flame, a wick produces a roughly spherical flame that radiates heat uniformly in all directions. Bourbigot summarizes the effect: "You get a ball of flame. This ball will create and radiate heat, sending heat into the local environment — the fire will spread that way."

How Researchers Are Tackling the Problem

A team of European researchers has received a grant through the Firespace programme to study ignition, flame spread and suppression in microgravity. Their work combines laboratory tests, parabolic flights, simulations and an upcoming rocket mission to deepen understanding and develop practical countermeasures:

- Acoustic Extinguishing: Guillaume Legros (Sorbonne University) is testing whether focused acoustic waves can suffocate flames in microgravity.

- Flame-Retardant Materials: Serge Bourbigot is evaluating materials and retardants whose performance may change when smoke and hot gases do not rise normally.

- Advanced Sensors: Florian Meyer (University of Bremen) is building sensitive temperature and gas sensors to detect early ignition and map fire propagation.

- Digital Simulations: Bart Merci (Ghent University) is developing computational models to simulate flame behavior in low-gravity environments and test suppression strategies virtually.

Some experiments have already been performed on parabolic flights that recreate roughly 20–25 seconds of weightlessness per parabola. To extend testing, Airbus will build a rocket mission planned within the next four years that aims to deliver about six minutes of microgravity for controlled flame experiments from a launch site in northern Sweden. The four researchers received a combined grant of €14 million (about $16 million) to fund their work over the next six years.

Why This Matters

Understanding and preventing fires in spacecraft is essential for crew safety on long-duration missions and for protecting expensive hardware. Solutions that work on Earth may behave differently in microgravity, so research into detection, material choice, active suppression methods and crew procedures will be central to future mission design — especially if oxygen policies change to reduce launch costs.

Bottom line: Flames in space behave differently, risks rise with higher oxygen, and scientists are combining experiments and simulations to develop new detection and extinguishing techniques before humans travel farther into the solar system.

Help us improve.