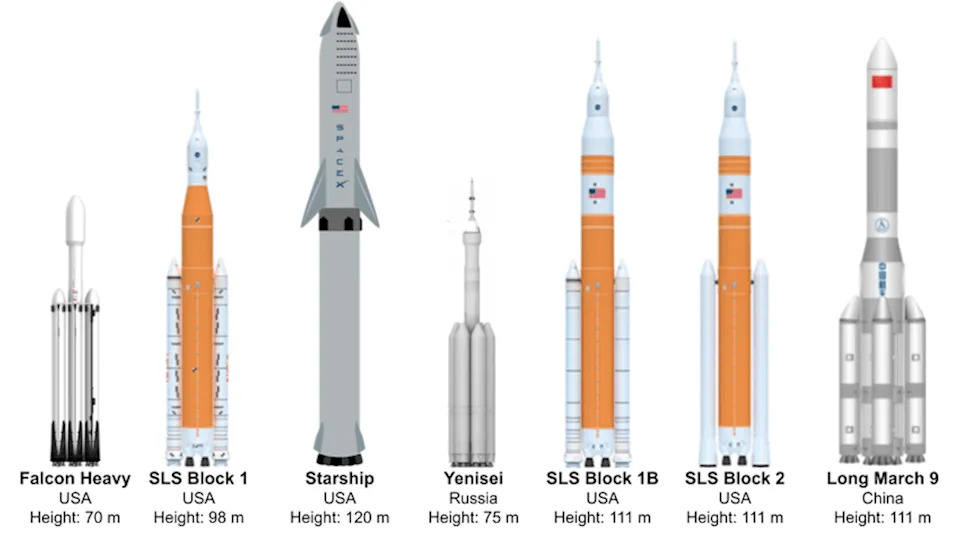

Superheavy-lift rockets such as SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn — both recently tested successfully — can deliver roughly 10× more mass and ~2× more fairing diameter to orbit. That extra capacity could remove the need for Webb-style folding mirrors, reducing complexity, risk and cost. Several concepts (Origins/Prima, a next-gen X-ray telescope, and GO-LoW) would exploit this to achieve ~100× sensitivity gains in their bands; if costs fall to half or a third of Webb’s, agencies might launch multiple Great Observatories within a decade, though disciplined budgeting is essential.

How Superheavy Rockets Could Make Space Telescopes Cheaper — And Transform Astronomy

After several dramatic setbacks, SpaceX’s enormous Starship achieved a fully successful test flight on Oct. 13, 2025, and with a few more checks could soon reach orbit. A month later, Blue Origin’s nearly as large New Glenn reached orbit and dispatched spacecraft toward Mars. These milestones matter not just for planetary exploration but for astronomy — the study of stars, galaxies and the broader cosmos — because superheavy-lift rockets could sharply reduce the cost and risk of space telescopes.

The Opportunity: More Mass, More Volume, Less Complexity

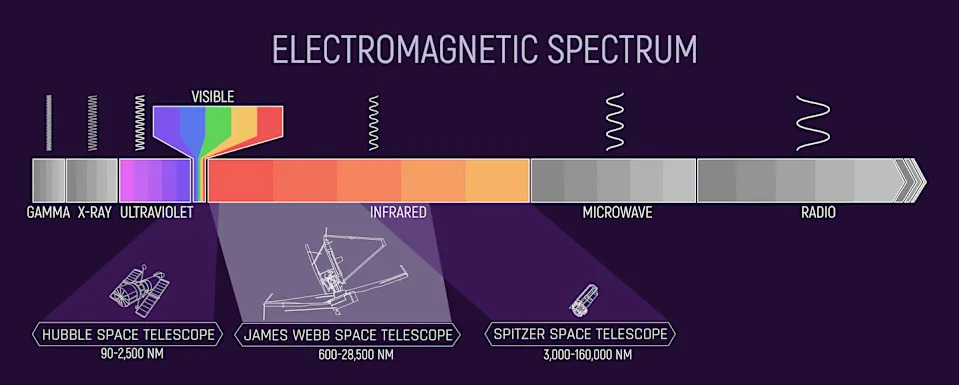

Space telescopes gain enormous scientific power by operating above Earth’s atmosphere, where they can observe across the electromagnetic spectrum — from long-wave radio and infrared to high-energy X-rays — much of which is blocked at the surface. But designing, building and launching flagship observatories has become increasingly expensive: the James Webb Space Telescope cost roughly US$10 billion and covers part of the infrared band.

Superheavy-lift rockets change the engineering trade-offs. For roughly the same launch budget, they can place about 10 times more mass into orbit and offer fairings roughly twice as wide as legacy rockets. That extra mass and volume reduces the need for the complex, high-risk folding mechanisms used to fit large mirrors into narrow launchers — the so-called origami engineering that Webb required — which in turn can lower both technical risk and program cost.

Why Size and Mass Matter

Telescope performance scales strongly with mirror size: larger mirrors collect more light and resolve finer detail. Achieving large apertures previously demanded lightweight, segmented mirrors and intricate deployment systems. Webb’s 6.5-meter mirror, for example, had to be both extremely lightweight and foldable to fit inside a 4‑meter launcher fairing. That choice introduced hundreds of potential failure points and drove up engineering, testing and manufacturing expenses.

By contrast, a wide, high-capacity rocket could launch Webb-scale or larger mirrors without folding, simplifying design and reducing many sources of risk and cost. That opens new design space: heavier, stiffer mirrors; simpler deployment; and more redundancy — all of which can improve performance and lower long-term program risk.

Concrete Concepts Taking Advantage of Superheavy Lift

At least three concept classes are already being pursued to exploit these capabilities:

- Origins / Prima — A deep-infrared observatory (Origins) and a smaller variant (Prima) that leverage larger apertures to study the cold universe: forming stars, planetary systems and the early stages of galaxy evolution.

- Next-Generation X-Ray Telescope — Concepts that use thicker, heavier X-ray mirrors to reach image sharpness and sensitivity comparable to Webb in their band, enabling detailed studies of black holes, hot gas and energetic transients.

- GO-LoW — A proposed very low-frequency radio array composed of roughly 100,000 small elements. Its mass-production design benefits directly from higher launch mass and could probe cosmic dawn and other low-frequency phenomena inaccessible from Earth.

All three concepts claim sensitivity improvements on the order of ~100× compared with predecessor missions in their respective bands, and would be at least comparable to Webb within their spectral ranges.

Cost Scenarios and Risks

If engineering and program management can reduce the cost of such observatories to roughly half of a Webb-class mission, agencies could potentially launch two flagship observatories for the price of one. If costs fall to a third, a complementary, spectrum-spanning set of Great Observatories becomes imaginable within a decade.

However, major caveats remain. The new rockets may not deliver promised cost or performance; initial development can be costly and schedules can slip. Equally important, astronomers’ continual push for “more light” risks resurrecting the very complexity that made Webb expensive. Space agencies will need disciplined budgetary control and clear prioritization: exploit the new payload and volume without letting ambition drive programs back into unaffordable complexity.

“More light” — as Goethe reportedly asked near the end of his life — captures scientists’ perpetual desire for greater capability. The challenge is balancing that desire with realistic budgets and robust engineering.

If agencies and the community can strike that balance, combining disciplined cost control with the broader design space enabled by superheavy-lift rockets, our understanding of the universe could advance dramatically within a decade or so.

Disclosure: This article is based on a piece by Martin Elvis (Smithsonian Institution), republished from The Conversation. The author reports no relevant financial relationships or conflicts influencing the article.

Help us improve.