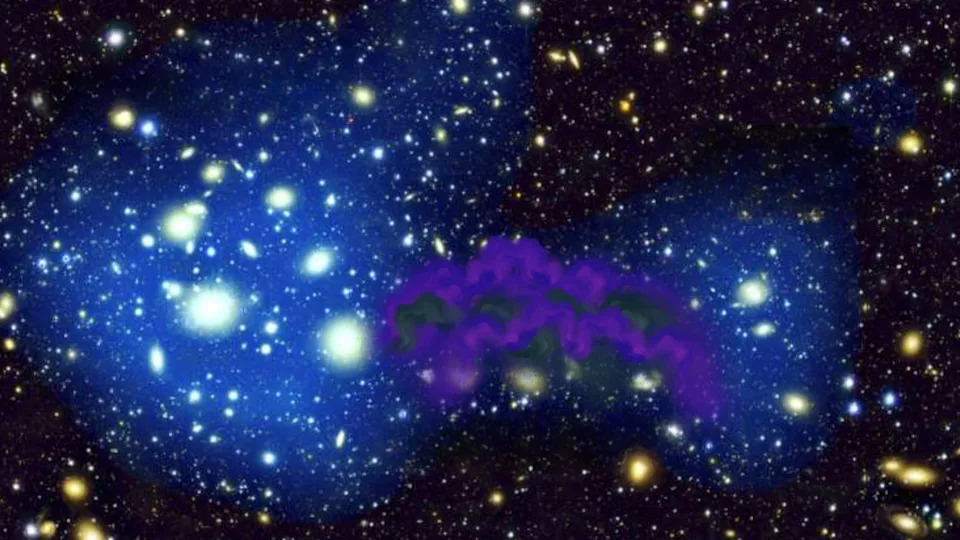

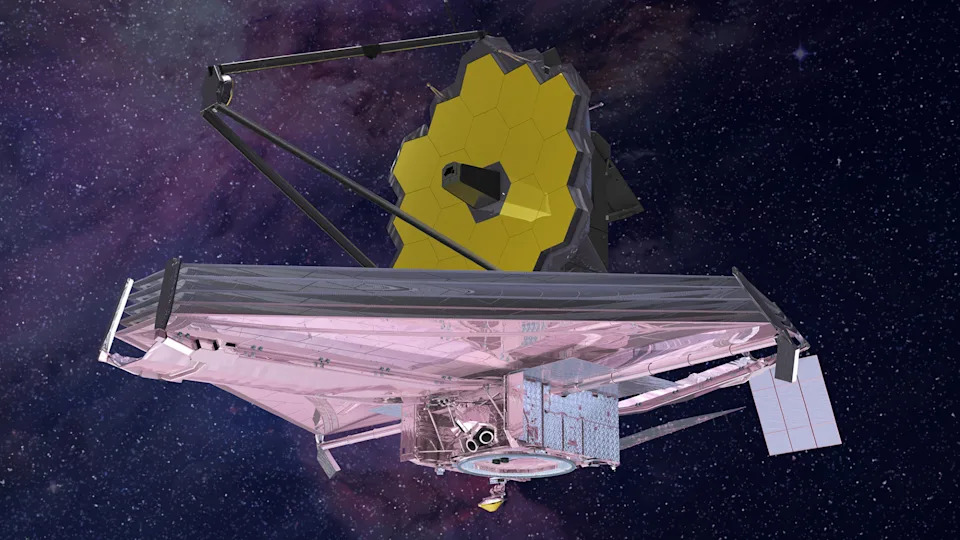

James Webb data from early 2025 revealed three unusually bright, highly redshifted objects that some scientists suggest may be "dark stars" — starlike bodies potentially powered by dark-matter annihilation rather than nuclear fusion. Predicted characteristics include low heavy-element content, cool photospheres, enormous radii (tens of astronomical units), and possible masses from ~10,000 to ~10 million solar masses. Smaller dark stars could later ignite fusion, while supermassive ones might collapse into black holes that seed early supermassive black holes. Further JWST spectroscopy and improved models are needed to distinguish dark stars from massive ordinary stars or galaxies.

When Darkness Shines: JWST's 'Dark Star' Candidates and How They Could Rewrite Early Star Formation

Scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) reported three unusually bright, highly redshifted objects in early 2025 that some researchers suggest may be examples of so-called "dark stars." If confirmed, these objects could change our understanding of how the first luminous structures formed — but the name "dark star" can be misleading.

What Is A Dark Star?

"Dark stars" are not truly dark, nor are they typical fusion-powered stars. The phrase refers to the proposed energy source that powers them: dark matter annihilation. In some theoretical models, dark-matter particles are their own antiparticles; when two meet, they annihilate and release energy. If enough dark matter is concentrated inside a collapsing primordial gas cloud, its annihilation could heat the gas and produce a starlike, luminous object without relying on nuclear fusion.

How They Might Form

In the conventional view, clouds of primordial hydrogen and helium collapse under gravity, heat up, and ignite nuclear fusion to become the first stars. The dark-star hypothesis (first seriously explored around 2008) suggests an alternative path: in regions with very high dark-matter density, annihilation heating could stall collapse and create a stable, extended object powered mainly by dark-matter energy rather than fusion. Such objects could persist as long as they accrete dark matter.

Predicted Characteristics

Models predict several distinctive traits for dark stars:

- They would be extremely ancient and therefore highly redshifted when observed from Earth.

- They should show little or no heavy-element (metal) signatures, since they form from primordial hydrogen and helium.

- They would have cooler photospheres than fusion stars of comparable luminosity but much larger radii, sometimes tens of astronomical units.

- Mass estimates vary widely: some scenarios predict masses of ~10,000 up to ~10 million times the Sun, depending on how much dark matter and gas they gather.

Why Astronomers Are Excited

JWST has found several high-redshift objects that appear brighter or more massive than expected for ordinary early galaxies or first-generation stars. Some researchers propose dark stars as one explanation. If true, dark stars would not only provide a novel astrophysical population but also offer a unique, large-scale probe of dark matter.

Possible End States

The fate of a dark star depends on its mass and dark-matter supply. Smaller dark stars that exhaust their dark matter could collapse further, with gravity igniting fusion and turning them into ordinary stars. In contrast, supermassive dark stars could collapse directly into black holes, potentially seeding the supermassive black holes seen at the centers of galaxies — and possibly explaining very massive early black holes such as the ~10 million–solar-mass object reported in UHZ-1 about 500 million years after the Big Bang.

Alternative Explanations And Needed Tests

The dark-star interpretation is not yet proven. Alternative scenarios — for example, extremely rapid baryonic accretion onto ordinary protostars or unusual compact star clusters and galaxies — could produce similar observational signatures. Distinguishing among them will require more JWST spectroscopy, tighter constraints on metallicity and size, variability studies, and better theoretical modeling of both dark-star atmospheres and massive protostellar accretion.

What Comes Next

Confirming dark stars would be transformative: it would provide the first non-gravitational evidence for dark-matter interactions on astrophysical scales and reshape ideas about the formation and early growth of stars and black holes. Upcoming JWST observations, complementary ground-based spectroscopy, and refined simulations will be essential to test whether any of the newly reported objects are truly powered by dark matter.

Bottom line: JWST's candidates are intriguing, but more data and better models are needed before we can say whether darkness is really shining in the earliest universe.