Richard Feinberg recounts a 1972 voyage from Anuta and uses that experience to explain how Pacific navigators crossed enormous ocean distances without Western instruments. Wayfinding combines celestial navigation, swell interpretation, reflected waves, bird behavior and mental maps of island networks. Historical records, ethnographic studies and experimental voyages such as Hōkūleʻa support the continuity and skill of Polynesian navigation traditions. Some regional phenomena like te lapa remain reported but scientifically unconfirmed.

How Pacific Wayfinders Crossed Thousands Of Miles Without Compasses Or GPS

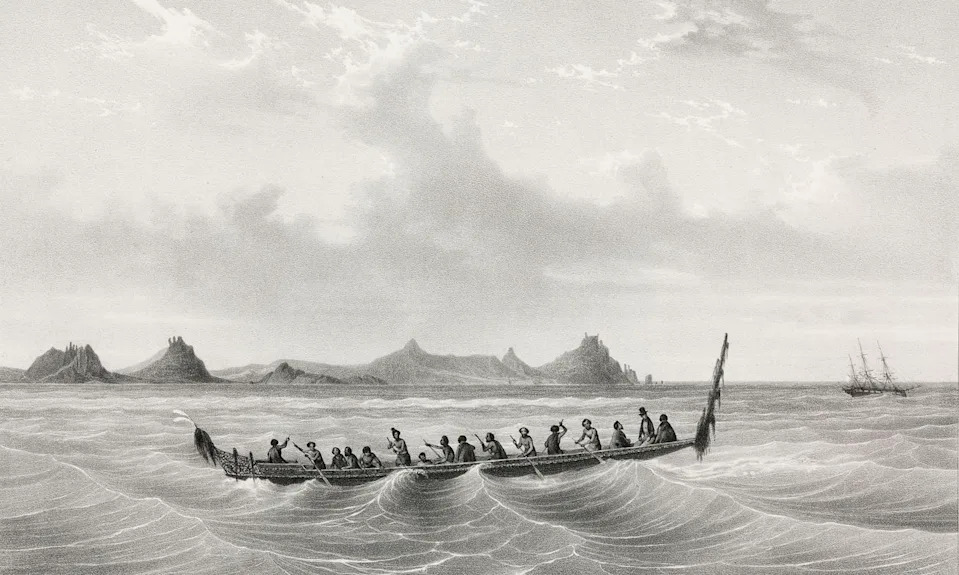

Wet and shivering, I climbed out of the outrigger after an exhausting afternoon and night at sea. Rain, wind and the lack of a flat surface made sleep impossible; my companions did not try. That voyage, in May 1972, was three months into doctoral fieldwork on Anuta, a remote island roughly half a mile across and about 75 miles (120 km) from its nearest inhabited neighbor. Anuta remains one of the few places where inter-island travel in outrigger canoes is still routinely practiced.

A Voyage to Patutaka

My hosts invited me on a bird-hunting trip to Patutaka, an uninhabited rock some 30 miles away. We spent 20 hours reaching the target, stayed two days, and returned under a 20-knot tailwind. That single trip launched decades of anthropological study into how Pacific Islanders cross vast ocean distances in small craft without modern instruments and reliably reach their destinations.

Three Strands of Evidence

Understanding Pacific navigation draws on three complementary lines of evidence: historical accounts, ethnographic documentation, and experimental voyaging. European explorers long admired Pacific seamanship: Louis Antoine de Bougainville called Sāmoa the Navigators' Islands in 1768, and James Cook praised Indigenous canoes and recorded the geographic expertise of the navigator Tupaia. In the 20th century scholars such as Te Rangi Hīroa summarized oral traditions, while ethnographers like Thomas Gladwin and David Lewis documented contemporary wayfinding practices.

Popular experimental voyages have also demonstrated the power of traditional techniques. Thor Heyerdahl's 1947 Kon-Tiki crossing stimulated interest, but perhaps the most influential experiment was the Polynesian Voyaging Society's Hōkūleʻa. Navigated by Mau Piailug, Hōkūleʻa sailed from Hawaiʻi to Tahiti in 1976 without instruments and later completed a global circumnavigation, reviving and validating indigenous navigation knowledge.

How Wayfinding Works

Wayfinding is not a single trick but a suite of interlocking knowledge systems. Navigators build mental maps of island networks and use cues from the sky, sea and living creatures to maintain course. The main tools and techniques include celestial navigation, swell interpretation, biological indicators and dead reckoning.

Celestial Navigation and Star Paths

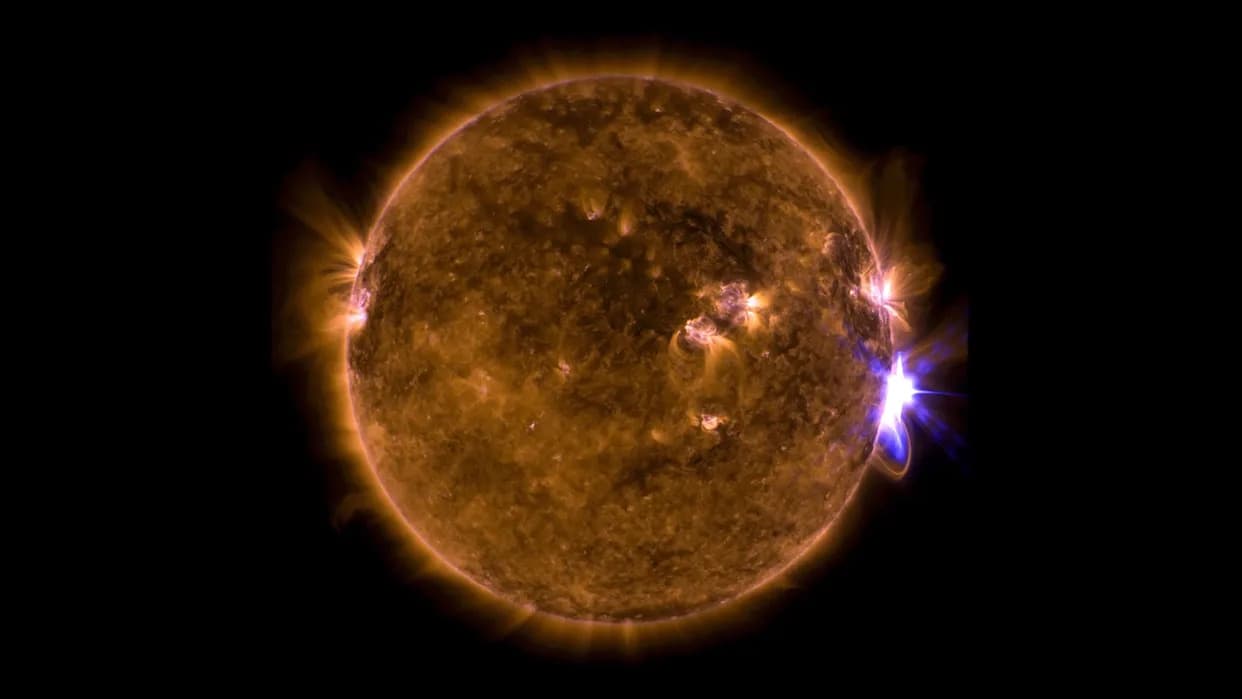

Near the equator many stars rise in predictable places on the horizon and trace similar parallels as they move. Navigators memorize star positions and follow sequences of alternate guide stars, called star paths, to stay on course as individual stars rise too high or set. The Sun plays a similar role when low on the horizon. Because star visibility and rising/setting points change seasonally, navigators maintain a detailed astronomical knowledge keyed to time of year.

Swell Patterns, Reflected Waves, And Birds

Ocean swells are perhaps the most distinctive non-instrument cue. Swells are long-period waves generated by distant, persistent winds and tend to hold a steady direction across thousands of miles. Skilled helmsmen feel these swells through the hull and use their direction to maintain heading, even at night. Reflected waves — swells that strike an island and bounce back — can signal approaching land before it becomes visible, and experienced mariners report detecting them by feel.

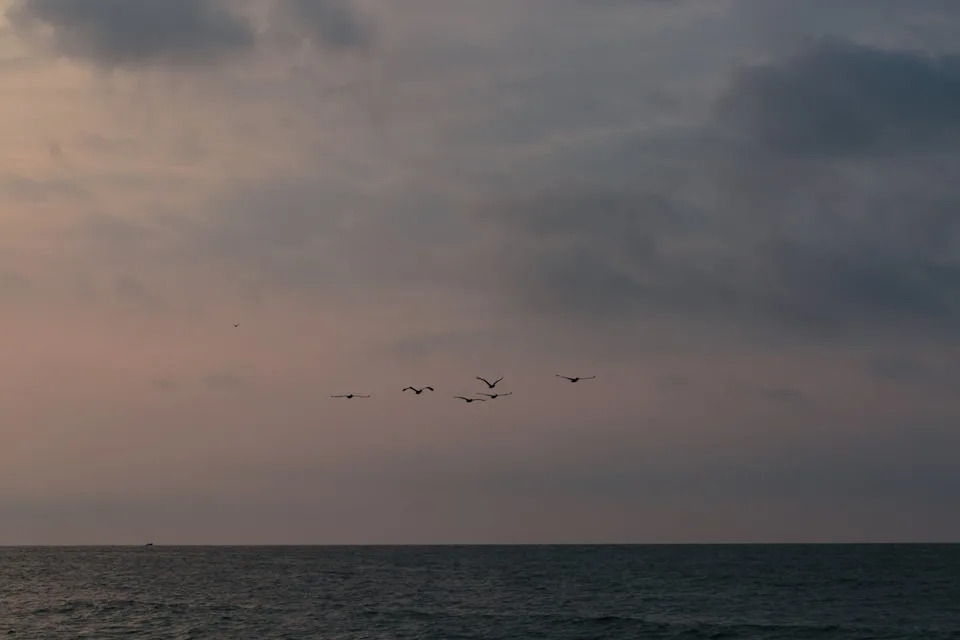

Biological cues are also important. Many seabirds nest on land and feed at sea; their morning and evening flight patterns can point toward islands. Sailors also look for changes in sky color, cloud formations over peaks, and other visual signs.

Estimating Position: Dead Reckoning And Etak

Longitude cannot be read directly from stars like latitude can, so navigators use dead reckoning: tracking time underway, speed and direction from a known starting point. Some Micronesian systems conceptualize position differently. Etak, for example, treats the canoe as stationary while a reference island is visualized as moving; mariners use angular relations between the canoe and that moving reference to mark progress. Scholars have proposed mechanisms for etak, but no single, universally accepted explanation exists.

Reported Phenomena And Scientific Caution

In some regions sailors describe phenomena such as te lapa, an underwater streak of light claimed to point toward islands. While some researchers report confidence in te lapa and speculate about bioluminescent or electromagnetic origins, other investigators — including the author after a year of searching — were unable to confirm it. Such reports remain contested and a reminder that oral knowledge and scientific verification can proceed on different timelines.

Knowledge Transmission And Cultural Legacy

For millennia, Pacific voyagers reached thousands of islands using this interwoven body of astronomical, oceanographic, meteorological and ecological knowledge. These skills were taught orally and through practice, passed across generations and reinforced by ritual, storytelling and apprenticeships. Modern ethnography and experimental voyaging have both preserved and energized these living traditions.

Conclusion: Pacific wayfinding is a sophisticated, resilient system built from detailed observation of the natural world and refined through generations of practice. It allowed mariners to traverse the planet's largest ocean long before compasses or GPS.

Help us improve.