Archaeologists led by Julia King have uncovered thousands of artifacts on a Rappahannock River bluff that corroborate villages described by John Smith more than 400 years ago. Finds—including beads, pottery shards, stone tools and clay tobacco pipes—match both Smith’s records and Rappahannock oral history. The discovery validates tribal memory, strengthens local land-preservation efforts, and highlights the value of combining documentary, oral and archaeological sources as the U.S. nears its 250th anniversary.

Lost Village Found: Archaeologists Unearth Artifacts from Settlement John Smith Described Along the Rappahannock

Archaeologists have uncovered thousands of artifacts on a bluff above the Rappahannock River that confirm the existence of an Indigenous settlement long described in John Smith’s 17th-century accounts and preserved in Rappahannock oral tradition. The discovery—led by anthropologist Julia King—offers material evidence that complements colonial records and tribal memory, and it may help the Rappahannock people protect and reclaim ancestral land.

How the Site Was Found

King’s team conducted targeted surveys along cliffland where earlier settlement models had suggested Native communities tended to favor locations with easier river access. Although areas like Fones Cliffs do not uniformly offer such access, the researchers focused on a bluff with fertile soils and ultimately encountered a broad scatter of artifacts across its plateau.

What Was Discovered

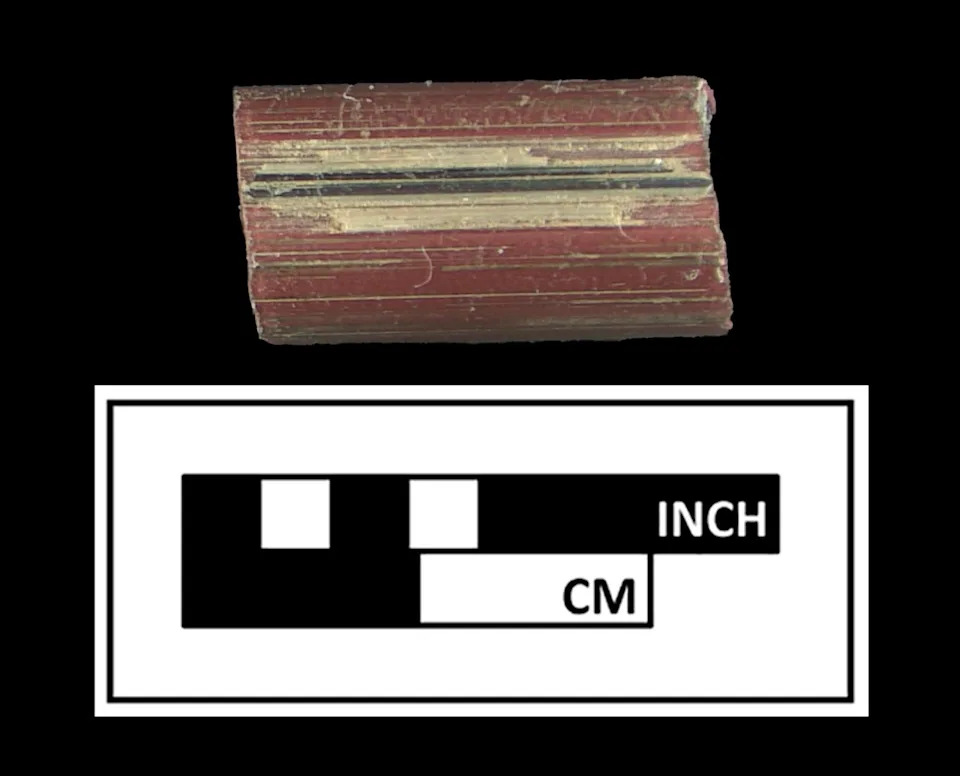

The excavations produced thousands of objects, including glass beads, pottery fragments, stone tools and clay tobacco pipes. These finds were distributed widely over the bluff rather than concentrated in a single small pit—evidence consistent with a substantial and sustained Indigenous occupation rather than random or isolated losses.

Historians often note Smith’s bravado, but he was also a meticulous recorder. As King observed, both written records and oral histories have strengths and limits, and archaeology helps bring them together with physical proof.

Collaboration With the Rappahannock

Out of caution and respect, King and her team withheld immediate public announcements until they had amassed what they called a "critical mass" of artifacts. When they were confident in the pattern of evidence, they informed Rappahannock Chief Anne Richardson. The finds validated long-standing tribal oral tradition and provide new support for the tribe’s efforts to preserve important sites.

Why This Matters

The discovery demonstrates the value of reading multiple sources—colonial maps and narratives, Indigenous oral histories, and archaeological data—'both with and against the grain,' as King puts it. It also reframes how we visualize early colonial landscapes: in 1608, the areas mapped by English explorers like Smith were predominantly Indigenous in population and organization.

Coming as the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, the find is a timely reminder that Native people remained present and active throughout the centuries of colonization, and that material evidence can restore chapters of history that have too often been overlooked.

Note: This story was produced in collaboration with Biography.com.