New research shows ancient cycads produce cone heat to attract beetle pollinators. Thermal imaging of Zamia furfuracea in Mexico revealed male cones warm in mid-afternoon and female cones about three hours later on a strict 24-hour circadian cycle. The plant gene AOX1 generates the heat while beetles detect it using TRPA1-equipped antennal sensors; disabling TRPA1 stops the beetles' heat response. The findings, published in Science, reveal infrared as a previously underappreciated channel of plant–pollinator communication and carry conservation implications for endangered cycads.

Ancient Heat Signals: How Cycads Use Warmth to Guide Beetle Pollinators

Blazing color and enticing scents are familiar ways plants attract pollinators — but some species use a different channel entirely: heat. New research reveals that cycads, an ancient group of seed plants, generate cone warmth that lures specialized beetles and coordinates pollen transfer.

Cycads have changed little since the Jurassic and bear stout trunks topped with stiff, featherlike leaves. They are dioecious, with separate male and female plants that produce pollen-bearing or ovule-bearing cones. Because thermogenesis is confined to cones, researchers hypothesized that heat might serve a reproductive purpose.

Daily Warmth Driven By A Biological Clock

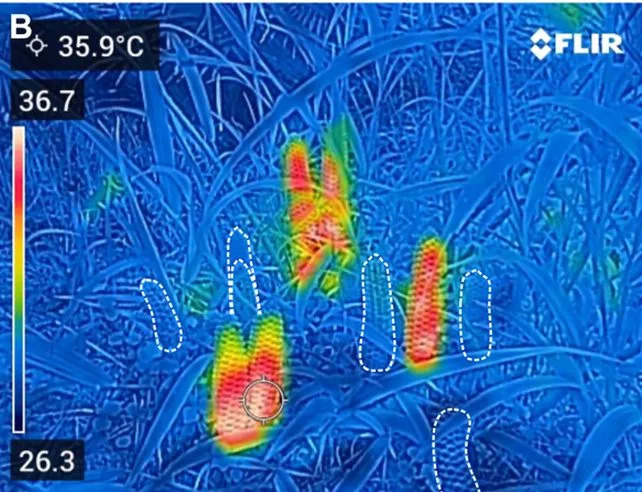

Using thermal imaging of Zamia furfuracea in Mexico, the team found cone temperatures follow a strict 24-hour circadian rhythm. Male cones begin warming in mid-afternoon, peak, and then cool; female cones heat up roughly three hours later. The repeatable daily cycle indicates an internal genetic clock, not immediate environmental triggers, controls cone thermogenesis.

Beetles Track Infrared Heat — And Move Pollen

The cycad depends on a single beetle species, Rhopalotria furfuracea, for pollination. As male cones warm, beetles aggregate there; when female cones warm later, the insects migrate and carry pollen between cones. Behavioral experiments that removed other cues showed the beetles home in specifically on radiant heat.

"Long before petals and perfume," says Harvard evolutionary biologist Wendy Valencia-Montoya, "plants and beetles found each other by feeling the warmth."

Molecular Mechanisms Connect Heat And Sensing

At the molecular level, cycads activate a gene called AOX1, which diverts mitochondrial metabolism away from ATP synthesis and releases chemical energy as heat. This sustained thermogenesis creates the infrared signal the beetles use to locate cones.

The beetles detect that heat with specialized sensilla at the tips of their antennae (coeloconic sensilla) that respond to thermal infrared via the TRPA1 ion channel — the same protein family involved in heat sensing in some vertebrates. When the researchers disabled TRPA1, beetles stopped responding to the thermal cue, providing the first direct link between TRPA1-mediated heat detection and pollination behavior.

Evolutionary And Conservation Implications

Only about 300 cycad species remain, most endangered. The authors suggest cycads’ reliance on a single-channel infrared signal — intensity only — may have become a disadvantage as flowering plants diversified during the Cretaceous (about 112–93 million years ago). Flowers offer complex color patterns and scent combinations that exploit insects' evolving visual and olfactory systems, while cycad-specialist beetles remained tuned to thermal cues, often at night.

This discovery expands our understanding of plant–animal communication by adding infrared heat to the list of signaling modalities alongside color and scent. The research appears in Science.

What This Means

Thermogenic pollination shows how deep and varied co-evolutionary strategies can be. It also highlights fragile, specialized relationships that conservation efforts must consider: protecting cycads means protecting their beetle partners and the environmental contexts that enable thermogenic signaling.

Help us improve.