New genetic and field evidence overturns a simple expectation of pollinator‑driven speciation. DNA shows the short, green flowers of the lipstick vine (Aeschynanthus acuminatus) evolved on the Asian mainland before the plants dispersed to Taiwan. Extensive camera‑trap observations (over 4,000 hours) found shorter‑billed birds visiting the green flowers in Taiwan and mainland sites; researchers also recorded the first rodent visits for this genus. The study challenges the classic Grant–Stebbins model and highlights ecological complexity and the value of fieldwork.

Lipstick Vine Surprise: Genetics Show Floral Shift Happened Before Plants Reached Taiwan

Plant biologist Jing‑Yi Lu and colleagues have uncovered a surprising twist in how a common Asian vine evolved: the short, green tubular flowers of the lipstick vine (Aeschynanthus acuminatus) appear to have evolved on the mainland before the plants colonized Taiwan—contradicting the simple expectation of the classic Grant–Stebbins model of pollinator‑driven speciation.

Background

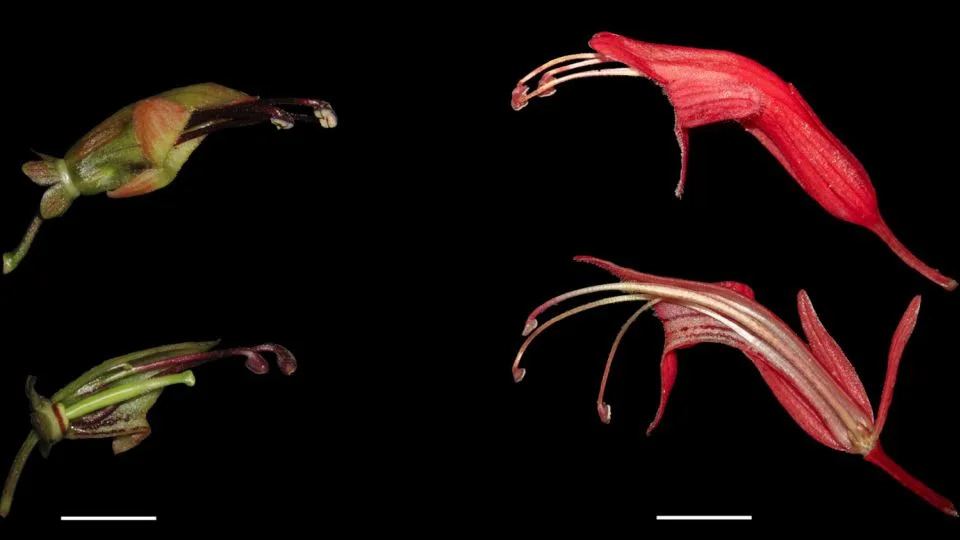

Across much of Asia, some lipstick vines bear long, bright red tubular flowers that are commonly pollinated by sunbirds. In Taiwan, however, Lu first noticed that local lipstick vines instead have short, yellowish‑green tubes. Because sunbirds are absent from Taiwan, the prevailing idea—summarized in the Grant–Stebbins model—would predict that a mainland ancestor arrived on Taiwan and then evolved shorter flowers to match the island’s shorter‑billed pollinators.

What the Researchers Did

Lu (who led the work while a doctoral student at the University of Chicago and is now a research associate at the Field Museum) and three colleagues combined field observation with genetic analysis. They ran more than 4,000 hours of camera‑trap observations at sites across Southeast Asia to document flower visitors and extracted and sequenced DNA from populations across the species’ range to reconstruct its evolutionary history.

Key Findings

The team found that:

- The green‑flowered form, Aeschynanthus acuminatus, is widespread across Southeast Asia, including mainland regions and Taiwan.

- Camera traps in Taiwan recorded a variety of shorter‑billed birds visiting the short, wide tubes—consistent with adaptation to local pollinators. Mainland green‑flowered populations were visited by both shorter‑billed birds and sunbirds capable of exploiting longer tubes.

- Genetic analyses showed that the green‑flowered lineage split from its long‑flowered relatives on the mainland before the green form dispersed to Taiwan—meaning the floral change predated colonization of the island.

“It was really surprising… Because the result did not follow the simple prediction by the classic model, we need to find some alternative explanation for it, and it’s kind of exciting and also kind of puzzling,” said Jing‑Yi Lu.

Interpretations and Open Questions

The authors and outside experts note several plausible explanations but no definitive answer. One hypothesis is that mainland sunbird populations declined at some point in the last few million years, reducing the effectiveness of specialized pollinators and favoring flowers that could attract a broader suite of visitors. However, the study found no direct evidence of a prolonged sunbird absence.

As Richard Ree, the study’s senior author and a curator at the Field Museum, put it: “It required a more complicated explanation. Ultimately, it still remains kind of mysterious how plants switch pollinators and evolve into new species while the ancestral pollinator is still present.”

Independent experts highlighted that the Grant–Stebbins model is a useful starting point but is a simplified verbal model; real‑world speciation often follows more complex paths driven by variable pollinator communities and environmental change.

Additional Notes and Significance

During their fieldwork in Vietnam the researchers also documented rodents visiting the vines—reported as the first record of rodent visitation for this genus—which underscores the diversity of ecological interactions that can influence floral evolution. The study was published in January in New Phytologist, and the team plans follow‑up papers on pollinator behavior and related species.

The findings emphasize the value of combining extensive field observations with genetic data to test evolutionary models, and they suggest that pollinator shifts and speciation can be driven by more complex historical and ecological dynamics than classical models predict. The work also reinforces the conservation importance of preserving both plants and their pollinators to maintain evolutionary and ecological processes.

By: Taylor Nicioli (freelance journalist). Study led by Jing‑Yi Lu and Richard Ree; published in New Phytologist. Institutions include the University of Chicago and the Field Museum of Natural History.

Help us improve.