Planetary defense has matured into a global system of telescopes, automated surveys and rapid analysis designed to find and track near‑Earth asteroids (NEAs). Ground programs like Catalina, Pan‑STARRS and ATLAS are being augmented by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and the planned NEO Surveyor space telescope, increasing discovery rates. Risk assessment uses rapid reporting to the Minor Planet Center, automated tools such as Scout and Sentry, and public metrics like the Torino Scale. Demonstrations such as NASA’s 2022 DART mission show deflection is possible but challenging; the 2029 close pass of 99942 Apophis will be a major scientific opportunity.

How Astronomers Find and Track Near‑Earth Asteroids — Inside Planetary Defense

Early this year a surprise space rock briefly triggered the International Asteroid Warning Network's highest alert since the network was formed in 2013. The object, 2024 YR4, initially showed a rising probability of impact — at one point estimated as 1-in-33 within eight years — and because its four‑year orbit meant it would not be observable again until 2028, the discovery left only a short window for follow-up observations and any potential response.

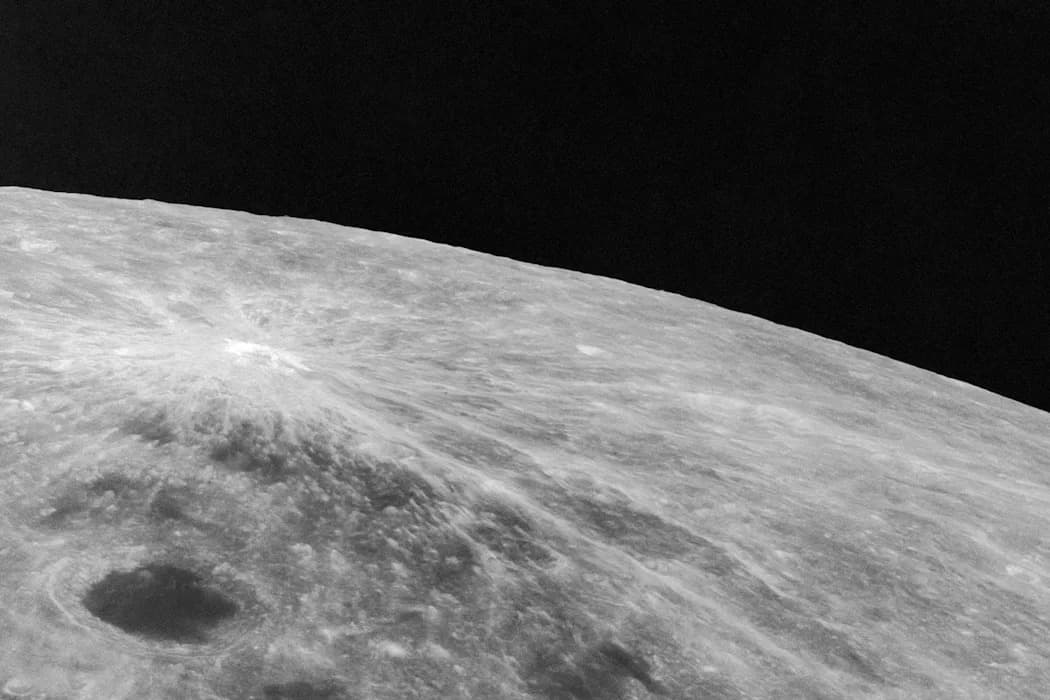

Additional weeks of tracking brought relief: refined measurements showed YR4 will miss Earth, though it still carried a modest chance of striking the Moon in 2032. The episode underscored both the power of modern sky surveys to detect threats and the reality that a truly dangerous near‑Earth asteroid (NEA) remains a matter of when, not if.

From a wake‑up call to an organized system

The modern field of planetary defense took shape after the dramatic 1994 impacts of Comet Shoemaker‑Levy 9 into Jupiter. The event convinced policymakers and space agencies that systematic searches were needed. In 1998, Congress directed NASA to find all asteroids larger than about 0.6 mile (1 km) — a threshold for global catastrophe — and agencies have steadily expanded capabilities ever since.

How surveys detect moving rocks

Searches have evolved from film plates to sensitive digital detectors and now to global networks of automated telescopes. Three full‑time ground surveys — the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) in Arizona, Pan‑STARRS in Hawaii, and the robotic ATLAS network (with sites in Hawaii, Chile and South Africa) — sweep the skies year‑round. Their efforts are being amplified by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which began operations recently, and by the planned space‑based NEO Surveyor mission (mid‑infrared) expected to launch later this decade.

Typical ground‑based operations involve repeated short exposures of the same field. Software processes images in real time to identify moving objects by comparing successive frames; observers then animate or blink these frames to confirm motion against the static starfield. Rapid reporting is essential: an object's visibility depends on the shifting geometry of the asteroid, Earth and Sun, and many discoveries are only observable for a narrow window.

People still matter

"Humans are integral to the Catalina Sky Survey," says CSS director Carson Fuls. "We manually review possible candidates because humans are highly adapted to detect slight motion."

Observers such as Greg Leonard, who operates a 27‑inch Schmidt telescope for CSS, routinely scan images for faint moving dots. CSS and similar programs use multiple telescopes for discovery and for rapid follow‑up, with some instruments optimized for fainter targets down to magnitude 22 (about a million times fainter than human vision).

From candidate to confirmed object

When software and a human reviewer agree on a candidate, detections are sent immediately to the Minor Planet Center (MPC) at the Center for Astrophysics, which posts candidate sightings worldwide so other observatories can perform follow‑up. Confirmed discoveries are processed and usually named within about 24 hours. To expand coverage, projects like The Daily Minor Planet on Zooniverse invite citizen scientists to vet additional candidate images, and thousands of volunteers have contributed discoveries.

Assessing risk: Scout, Sentry and the Torino Scale

The Center for Near‑Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) analyzes reported objects with tools such as Scout, which evaluates preliminary trajectories and short‑term impact probabilities for unconfirmed candidates. The MPC runs Sentry to assess the confirmed catalog for potential impacts up to 100 years ahead. Risk is commonly communicated with the Torino Impact Hazard Scale (0–10), which ranges from negligible (0–1) to certain, catastrophic impacts (8–10).

Although early headlines can be dramatic, most high‑profile candidates quickly fall to low Torino levels as more data arrive. For example, YR4 peaked at Torino level 3 and is now rated 0.

Populations, progress and the size problem

How complete our catalogs are depends strongly on size. Paul Chodas of CNEOS estimates roughly 24,000 NEAs are 140 meters (460 feet) and larger; surveys have found about 9,600 NEAs overall and roughly 900 larger than 1 kilometer (0.6 mile). At the 140‑meter threshold NASA estimates roughly 45% of the population has been discovered. Smaller objects are far more numerous: a 60‑meter rock like YR4 is one of an estimated ~100,000, and meter‑scale objects number in the billions.

Can we deflect a threatening asteroid?

Detection is only half the challenge; deflection methods are the other. NASA’s 2022 Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) demonstrated that a kinetic impactor can change an asteroid’s orbit: DART struck Dimorphos, a 160‑meter moonlet of Didymos, shortening its orbital period by 32 minutes. The change was measurable but small, indicating that larger threats would require much greater force or very early intervention. As David Jewitt and colleagues note, scaling deflection for much larger objects would be technically demanding, and the DART impact also produced a debris cloud — including house‑sized boulders — that investigators will study further with ESA’s Hera mission.

Recent events and notable upcoming encounters

Smaller impacts continue to surprise us; the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteoroid exploded over Russia with energy equivalent to dozens of kilotons of TNT, injuring hundreds. Nevertheless, tracking and predictive systems have matured: several recent entries were forecast to within seconds and a kilometer after only hours of data collection.

One high‑visibility future event is the April 2029 close approach of 99942 Apophis. Discovered in 2004 and roughly the size of an aircraft carrier, Apophis will pass within about 20,000 miles (32,000 km) of Earth — closer than many geosynchronous satellites — but current observations show it will safely fly by and pose no threat for at least a century. NASA and ESA plan science missions around this encounter to study how Earth's tides and other forces affect such bodies.

Conclusion

Planetary defense has grown from ad hoc searches to an integrated, international system combining advanced surveys, rapid data sharing, automated analysis and human review. New observatories and spacecraft will continue improving detection rates and characterization, but success also depends on international coordination, sustained funding and public engagement. While no system guarantees absolute safety, our growing capabilities make it increasingly likely we will spot — and, with enough warning, respond to — the next uninvited cosmic visitor.

Help us improve.