Researchers analyzing TESS data compared main‑sequence and post–main‑sequence stars and found that close‑in planets are much rarer around evolved stars. From a sample of 456,941 evolved stars the team identified 130 close‑in planets or candidates, and models indicate tidal orbital decay and eventual engulfment explain the decline. Improved metallicity measurements and future missions like ESA's PLATO (Dec 2026) will refine the rates and may allow detection of planets spiralling inward.

Planet‑Eating Stars Offer a Preview of Earth's Distant Fate

Our Sun is roughly halfway through its lifetime, and astronomers are now seeing observational evidence that illustrates how planets around Sun‑like stars can disappear as their hosts age. Using data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), researchers have compared younger, main‑sequence stars with older, post–main‑sequence (evolved) stars and found that close‑in planets become significantly rarer around aging stars.

Study and Data

Edward Bryant (University of Warwick) and Vincent Van Eylen (University College London) searched TESS observations for evolved stars and identified a sample of 456,941 post–main‑sequence stars. From that sample they found 130 close‑in planets and planet candidates. By comparing planet occurrence around these evolved stars with that around main‑sequence stars, the team uncovered a clear decline in the frequency of short‑period planets as stars evolve.

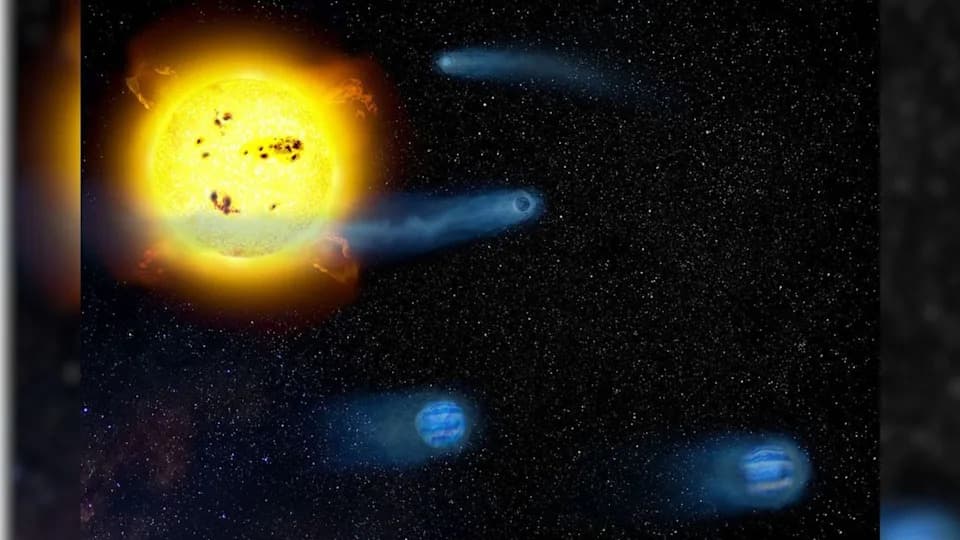

How Planets Disappear

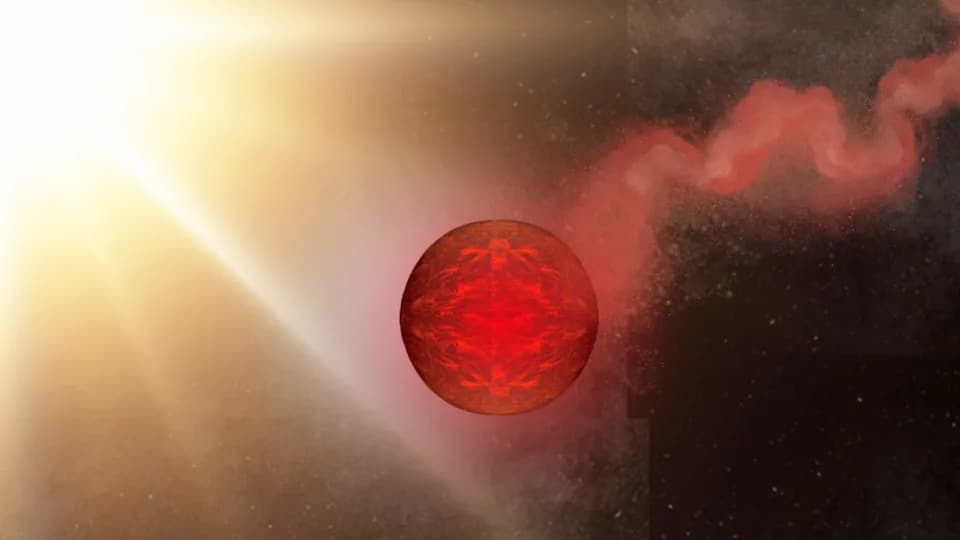

Expanding stars can destroy nearby planets in several ways. As a star leaves the main sequence it swells into a giant, potentially engulfing any planets in close orbits. Even before direct engulfment, stronger tidal forces from an expanded star can drive orbital decay, stripping atmospheres, shrinking orbital radii, and in extreme cases tearing planets apart. Bryant and Van Eylen modelled tidal orbital decay and found the observed drop in close‑in planet occurrence is consistent with these processes.

"We saw that these planets are getting rarer [as stars age]," Bryant said. "We're fairly confident that it's not due to a formation effect, because we don't see large differences in the mass and broad chemical properties of these stars versus the main‑sequence population."

Detection Challenges

TESS detects planets via the transit method, which measures tiny dips in starlight as planets cross their hosts. Transits are easiest to detect for large planets in tight orbits. For evolved stars the challenge is greater: a planet of a given size blocks a smaller fraction of light from an expanded star, so transit signals are shallower and harder to find. That selection bias means the observed planet counts around giants are conservative; nevertheless, the statistical difference versus main‑sequence samples remains strong.

Metallicity, Ages, and Uncertainties

Older stars typically have lower metallicity (fewer elements heavier than helium), and metallicity correlates with planet occurrence. As Sabine Reffert (Universität Heidelberg) — who was not involved in the study — notes, modest metallicity differences could change the inferred occurrence rates. Better spectroscopic metallicity and mass measurements for both stars and planets will refine the conclusions, though the overall trend of fewer close‑in planets around evolved stars is robust.

Future Observations

Upcoming and ongoing missions will improve the picture. ESA's PLATO mission, scheduled for launch in December 2026, will provide more sensitive, longer‑baseline photometry that complements TESS. Combined with targeted spectroscopy to measure stellar metallicities and precise masses, these data could reveal minute orbital decay signatures — direct evidence of planets spiraling toward ingestion by their aging stars.

What This Means for Earth's Long‑Term Future

These findings do not imply any imminent danger for Earth — the Sun's red giant phase is at least ~5 billion years away — but they do offer a valuable observational preview. By studying Sun‑mass stars as they evolve, astronomers can better understand the processes that will eventually shape the final architecture of our own Solar System.

Help us improve.