The article describes how samples collected from a Vermont cheese cave revealed rapid evolution in a rind fungus. Researchers found that Penicillium solitum went from greenish-brown to white because a disruption in the alb1 gene halted melanin production. In the cave’s darkness, melanin was no longer beneficial, so the pathway was lost by relaxed selection, allowing the fungus to reallocate energy to growth. The case illustrates evolution in a food-production setting and suggests ways cheesemakers might shape microbial communities.

When Cheese Rinds Evolve: Cave Molds Lose Their Color — and What That Reveals About Evolution

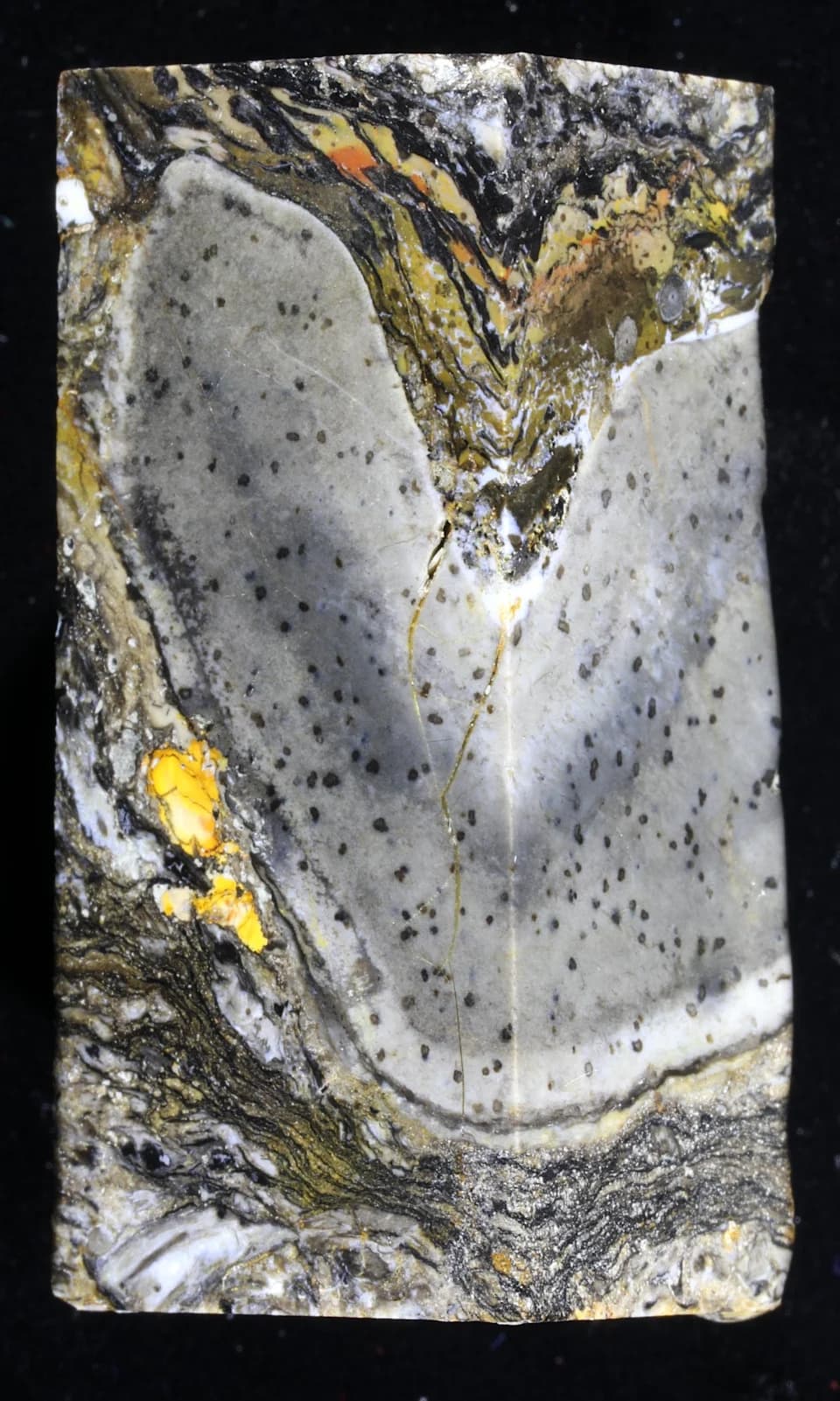

Tufts University microbiologist Benjamin Wolfe once collected rind samples from a Vermont cheese cave during a memorable visit. He froze those samples and years later his graduate student, Nicholas Louw, returned to the same farm and found the cheese rinds had changed dramatically: what had been a mottled greenish-brown surface dominated by a filamentous fungus was now uniformly white.

Genetic analysis by Louw, Wolfe and collaborators traced the shift to a disruption in a gene called alb1, which is involved in melanin production. The fungus, identified as Penicillium solitum, stopped producing the greenish-brown pigment because the melanin pathway had been genetically silenced.

How did that happen? The researchers interpret the change as an example of relaxed selection. In the cave’s dark interior, melanin—useful for shielding fungi from ultraviolet light—is no longer advantageous. Maintaining pigment production costs energy, so losing that pathway can free resources for growth and other survival functions.

"This was really exciting because we thought it could be an example of evolution happening right before our eyes," Wolfe said, noting that neither the cheesemaking routine nor the cave environment had changed.

The case is a clear, small-scale example of evolution in a managed food environment. It underscores how microbial communities on food can adapt rapidly to local conditions. For cheesemakers and food microbiologists, watching rind microorganisms evolve suggests opportunities to intentionally cultivate or select microbial communities to shape texture and flavor.

Implications

Beyond the novelty, this finding has practical value: understanding which genes and pathways change under particular production conditions can help producers manage rind communities more predictably. It also provides a tangible classroom example of evolutionary processes such as mutation and relaxed selection acting on real populations.

Help us improve.