Researchers used a multi-messenger imaging technique at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to capture the clearest observations yet of laser-driven shockwaves relevant to inertial confinement fusion. Firing synchronized lasers at a superthin water jet and combining X-ray with electron-beam imaging, the team produced ultrafast movies that resolved shock behavior on trillionth-of-a-second timescales. They discovered an unexpected thin water-vapor layer that improved compression symmetry—an effect not predicted by existing simulations—highlighting gaps between models and experiment that could inform better fusion target design and diagnostics.

Scientists Capture the Most Detailed Images Yet of Shockwaves That Trigger Nuclear Fusion

Researchers have recorded the clearest, highest-resolution observations to date of laser-driven shockwaves that play a critical role in initiating nuclear fusion—an advance that sharpens diagnostics for next-generation fusion research.

Advanced Imaging Reveals Ultrafast Shock Dynamics

A new study published in Nature Communications reports that a University of Michigan–led team, working through the Department of Energy's LaserNetUS program, used a multi-messenger imaging approach to track how laser-driven shockwaves form and evolve on ultrashort time and length scales. The experiments were carried out at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

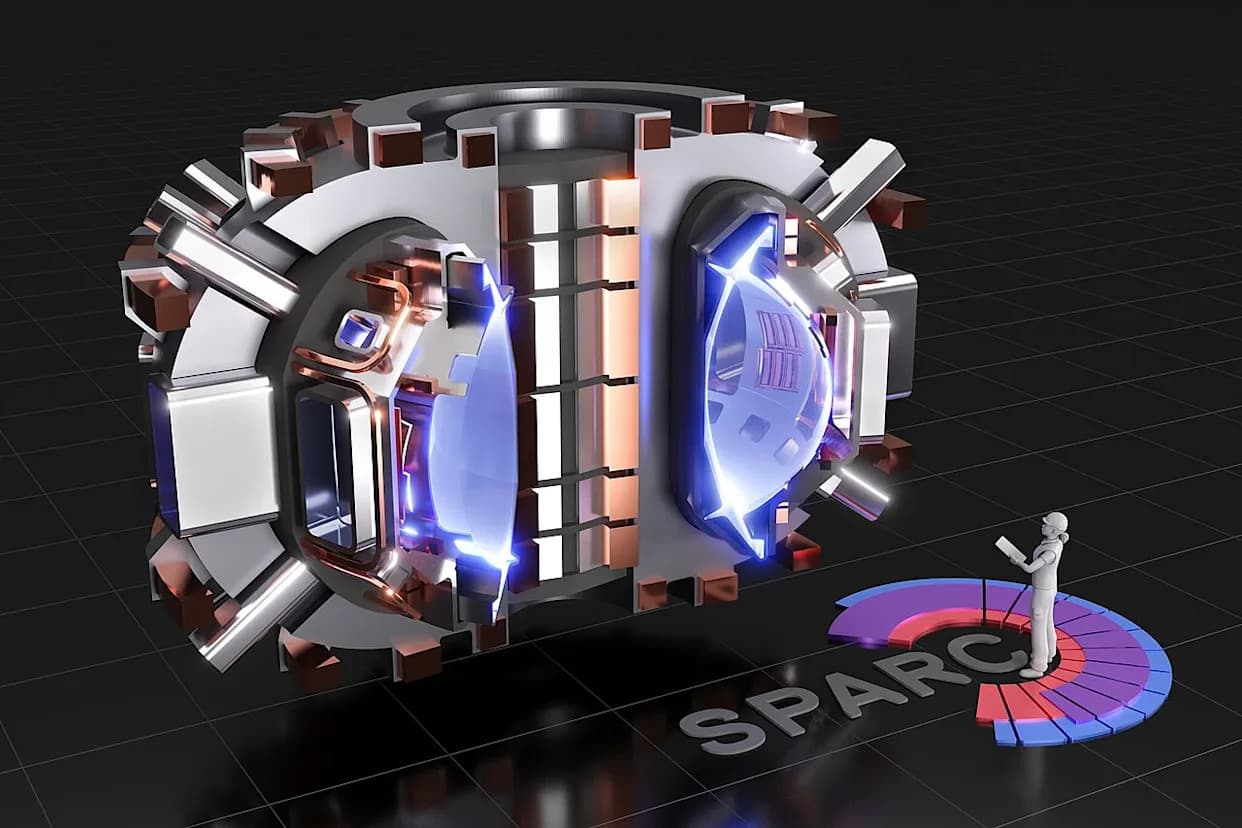

Inertial confinement fusion—one route to practical fusion power—relies on powerful lasers that strike a fuel capsule to create shockwaves that compress the fuel to extreme temperatures and pressures. Because the process is highly sensitive, small instabilities or asymmetries can prevent efficient fusion burn.

How the Experiment Worked

To probe shock behavior safely and precisely, the researchers fired synchronized laser pulses at a superthin, flowing water jet used as a surrogate for fusion fuel. By combining X-ray imaging with high-energy electron-beam probes, the team produced ultrafast movies that resolved shock dynamics on trillionths-of-a-second timescales.

'We wanted to demonstrate that the X-rays produced by extremely intense lasers have unique properties that allow us to capture a movie of the extremely fast motion of plasma,' said Alec Thomas, a plasma physics researcher at the University of Michigan and a co-author of the paper.

Key Discovery: A Hidden Vapor Layer

The measurements revealed an unexpected, thin layer of water vapor enveloping the jet. That vapor layer helped the shock compress the material more evenly—an effect similar to how low-density foam layers are used on inertial confinement targets to improve symmetry. According to the authors, this vapor-driven effect was not predicted by existing computer simulations.

'Every time we looked at the X-ray image, it surprised us,' said Hai-En Tsai of Berkeley Lab. 'The simulations were very different from what we actually saw.'

Why This Matters

Identifying gaps between simulations and experimental behavior is essential for improving target design, diagnostics, and predictive modeling. Better diagnostics and more accurate models can reduce instabilities that limit fusion performance and help guide future experiments that aim to make fusion more efficient and reliable.

While commercial fusion power remains years away, advances in high-resolution diagnostics such as this study are important milestones. They bring researchers closer to harnessing a potentially low-carbon energy source that could complement renewables like wind and solar and help reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Help us improve.