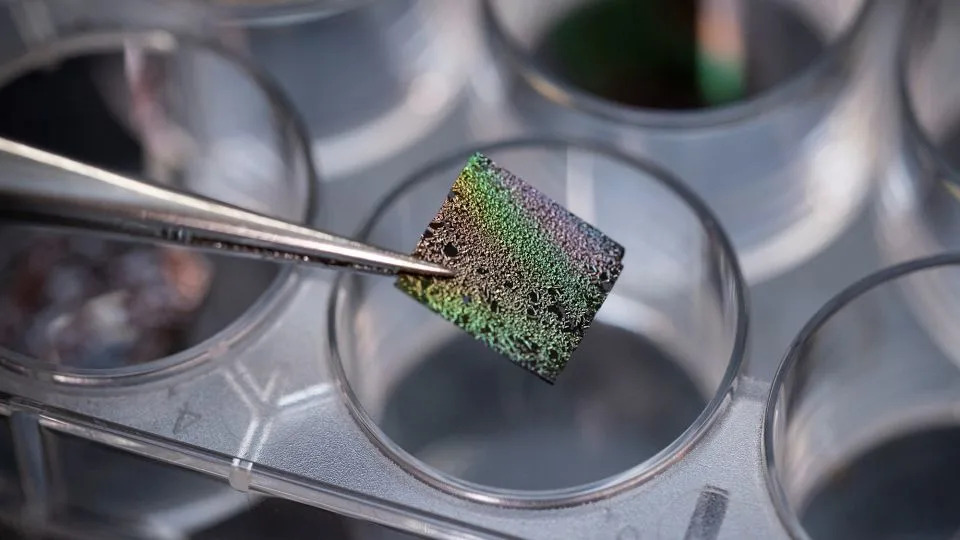

Linda Losurdo, a PhD student at the University of Sydney, produced a few milligrams of dusty nanoparticles by applying 10,000 volts to a mix of nitrogen, carbon dioxide and acetylene, creating a glow-discharge plasma that mimics star‑like environments. The lab-made dust, deposited on silicon wafers, represents a pristine analogue of cosmic dust and can help test whether organic building blocks such as amino acids form in space. External experts praised the method as a useful bridge between telescopic observations and laboratory experiments, and the team plans to vary conditions to build a library of dust types that could be matched to meteorites.

PhD Student Recreates Cosmic Dust in a Lab, Offering New Clues to the Origins of Life

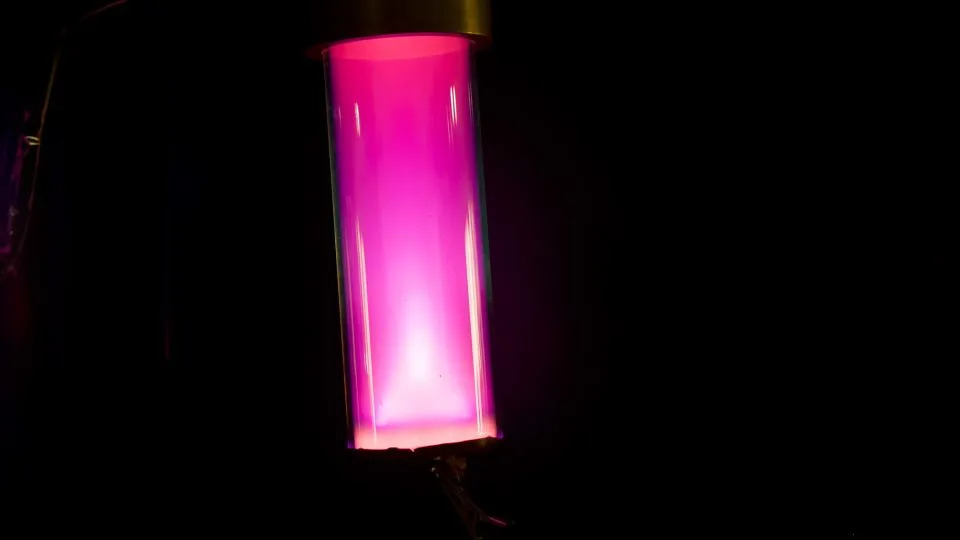

Recreating a small piece of the universe in a glass tube may sound like science fiction, but that is exactly what Linda Losurdo achieved in her laboratory at the University of Sydney. A doctoral student in materials and plasma physics, Losurdo used a simple mixture of gases and a high-voltage discharge to produce a few milligrams of dusty nanoparticles that mimic pristine cosmic dust.

How the Dust Was Made

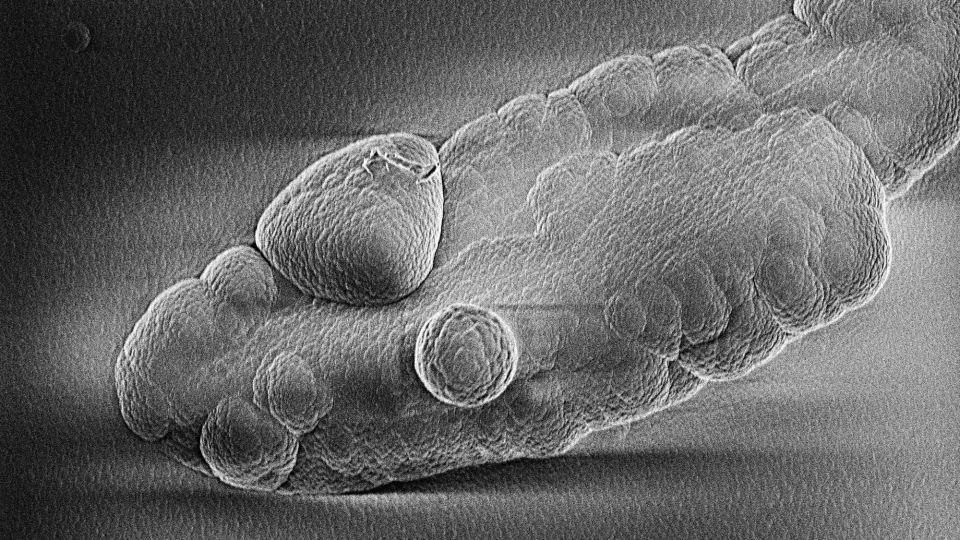

Losurdo and coauthor David McKenzie, a professor of materials physics, began by evacuating a glass tube and filling it with nitrogen, carbon dioxide and acetylene. They then applied 10,000 volts across the tube for about an hour, creating a glow-discharge plasma. The energized gas strips electrons from atoms and drives chemistry that causes atoms and molecules to coalesce into solid particles.

“When we examine big questions such as the origins of life, we must trace where the building blocks began. Where did all the carbon on Earth originate, and what journey did it take before it could assemble into structures such as amino acids?” Losurdo said.

What They Found

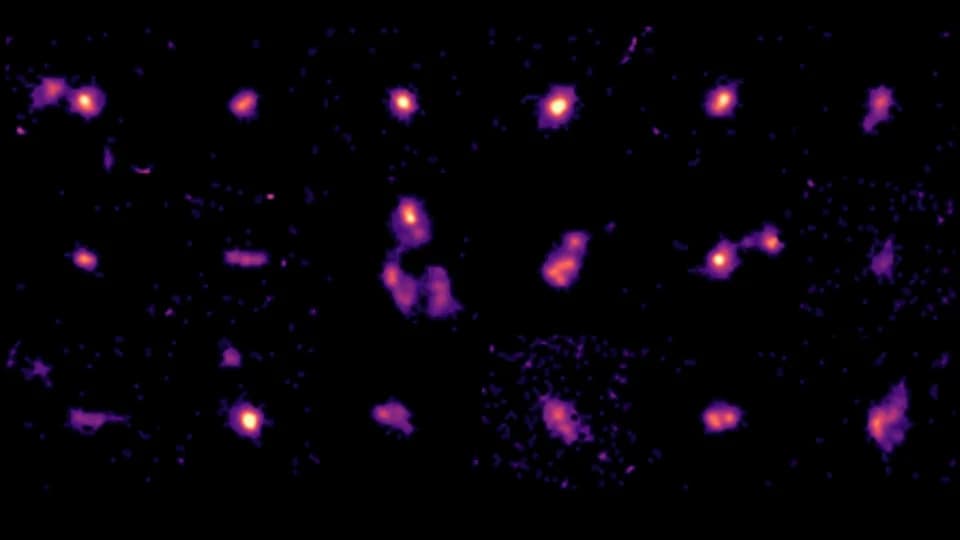

The experiment yielded a few milligrams of so-called dusty nanoparticles. Because the particles are tiny and delicate, the team let them deposit onto silicon wafers, which provide a clean background for imaging and chemical analysis. The lab-made dust resembles the fresh, pristine form of cosmic dust before it undergoes further chemical processing in space or inside comets and meteorites.

Why It Matters

Cosmic dust plays a central role in star formation and serves as a substrate and catalyst for the organic molecules that can be precursors to life. Laboratory analogues let researchers test whether key molecules such as amino acids might form in stellar or interstellar environments, rather than originating solely on early Earth. Producing repeatable, well-characterized samples in the lab fills a gap left by rare and often altered samples returned from space.

Expert Reactions and Next Steps

External scientists praised the approach. Martin McCoustra of Heriot-Watt University called the study convincing, noting that chemical complexity in space can evolve from simple molecules deposited on dust grains. Tobin Munsat (University of Colorado Boulder) emphasized that lab analogues under controlled conditions are essential for interpreting the natural world. Damanveer Grewal (Yale University) said the results provide a promising bridge between telescopic observations and laboratory analysis.

The research team plans to vary gas mixtures, voltages, durations and substrates to build a library of dust types that could be compared with specific meteorites and astronomical sources. Their goal is to better match lab samples with dust seen around giant stars, supernova remnants and nebulae.

Publication

The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal of the American Astronomical Society.

Help us improve.