Summary: New theoretical work suggests that Hawking-like evaporation could affect not only black holes but also ultradense, horizonless objects such as white dwarfs and neutron stars. Including these evaporation channels yields an estimated upper bound for cosmic longevity of about 1078 years—far shorter than some previous estimates that neglected horizonless decay. These processes are purely theoretical refinements and pose no practical risk to humanity on any foreseeable timescale.

Scientists Say The Universe May Quietly Fade Away Far Sooner Than Thought

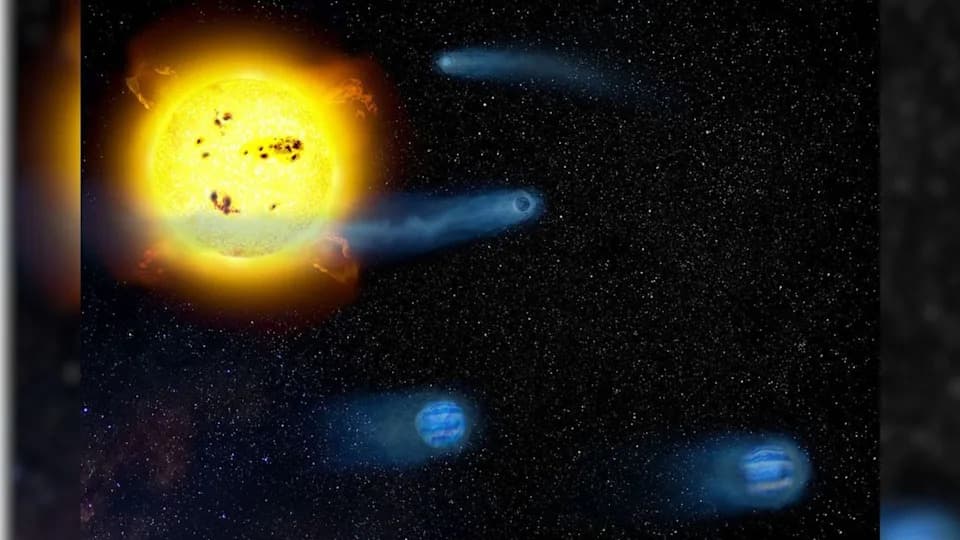

Despite the dramatic birth implied by the Big Bang, new theoretical work suggests the universe’s end may be a long, quiet fade rather than a cinematic explosion.

What the researchers propose: Astrophysicist Heino Falcke, quantum physicist Michael Wondrak, and mathematician Walter van Suijlekom argue that Hawking-like evaporation may not be unique to black holes. In a 2023 paper in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, they suggest that ultradense, horizonless objects such as white dwarfs and neutron stars can slowly lose mass through gravitational pair production and related quantum effects.

How the mechanism works: The familiar picture of Hawking radiation involves particle–antiparticle pairs forming near a black hole’s event horizon; one particle falls in while its partner escapes, producing a faint flux of radiation. For objects without event horizons, the authors propose that pair production occurs both outside and inside the body. Many produced particles strike and are absorbed by the surface, changing internal energy and producing a surface emission that drives gradual mass loss.

Why this changes cosmic timelines: Because all mass curves spacetime, even objects without event horizons can generate gravitational pair production. The stronger the curvature (i.e., the denser the object), the faster the evaporation. Taking these additional channels into account, the team estimates an effective upper bound on cosmic longevity around 1078 years for many of the densest structures—vastly shorter than some earlier estimates that reached ~101100 years by neglecting horizonless evaporation.

Estimated lifetimes (order-of-magnitude): White dwarfs, supermassive black holes, and dark-matter supercluster haloes could persist up to roughly 1078 years; neutron stars and stellar-mass black holes might last nearer 1067 years. Even ordinary matter is not exempt—human-scale objects are estimated to take on the order of 1090 years to vanish through these processes, far beyond any biological or geological timescale but finite in principle.

Black holes vs. Horizonless Objects: Paradoxically, although black holes have extremely strong gravity that accelerates evaporation, their lack of a surface and ability to reabsorb some escaping particles can delay complete evaporation compared with a similarly dense object that has a surface.

“Using gravitational curvature radiation, we find that also neutron stars and white dwarfs decay in a finite time in the presence of gravitational pair production,” the authors write.

What this means for us: This is a theoretical refinement of long-term cosmic forecasts and does not affect human or planetary timescales. Earth faces no risk from these processes for roughly 5 billion years—the timescale on which the Sun will become a red giant. The new work instead sharpens our understanding of the very far future: given enough time (on the order of 1078 years), all structured matter would have faded into particles and radiation.

Context and caveats: These results are theoretical and depend on our current understanding of quantum fields in curved spacetime. The ideas link to long-standing questions like the Hawking information paradox and remain areas of active research and debate. Observational confirmation is effectively impossible on human timescales, but the proposals help refine models of cosmic fate.

Bottom line: The universe’s end may be less explosive and more inevitable: a slow evaporation of all matter driven by quantum effects in gravitational fields—potentially occurring much sooner (in cosmological terms) than some earlier, more optimistic estimates.

Help us improve.