Luna 9, the Soviet spacecraft that made the first soft landing on the Moon in 1966, has not been definitively located despite modern orbital mapping. Researchers using triangulation of the probe's 1966 panoramas and machine-learning scans of LRO images have proposed candidate sites, including coordinates about 25 km from the Soviet-reported landing spot. A targeted Chandrayaan-2 imaging pass in March 2026 at ~0.25 m/pixel could confirm whether a pixel-scale anomaly is the surviving 100‑kg spherical capsule. Confirming Luna 9 would offer both historical closure and a chance to study decades-long effects of the lunar environment on materials.

Where Did Luna 9 Land? The 1966 Soviet Lander Still Hides on the Moon — A New Search May Reveal It

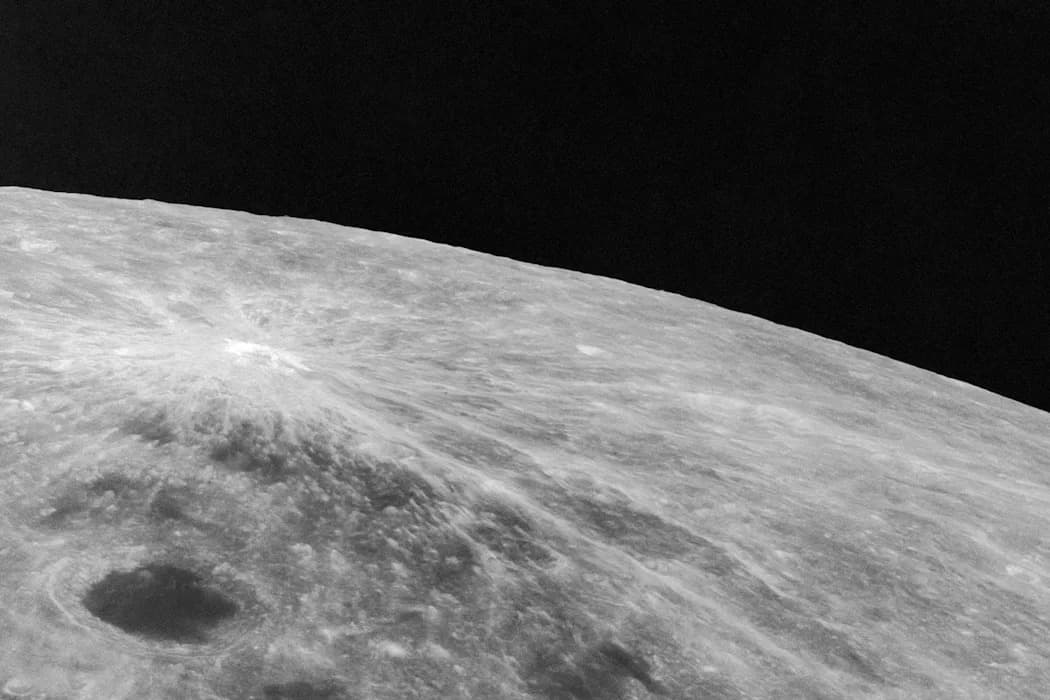

Sixty years after the Soviet probe Luna 9 achieved the first soft landing on another world, its exact resting place on the Moon remains unconfirmed. Despite high-resolution lunar maps from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and India’s Chandrayaan-2, the surviving piece of hardware — a 100‑kg spherical capsule — is so small that it has so far escaped unambiguous detection.

Why Luna 9 Matters

Luna 9 touched down in Oceanus Procellarum on 3 February 1966 and proved a critical technical milestone: it showed the lunar surface could support a lander, dispelling fears of a deep, swallowing dust layer. The mission transmitted three panoramas and a handful of scientific measurements during its roughly three days of battery-powered operation.

The Oddball Design and What Survived

Instead of traditional landing legs, Luna 9 ejected a 100‑kg spherical capsule encased in inflatable shock absorbers from about five meters above the regolith. That sphere bounced, came to rest, and unfolded four petal-like panels to stabilize its instruments. The heavier 430‑kg descent stage crashed nearby. Of roughly 1.5 metric tons launched, only the small sphere remained functional on the surface.

Why Finding It Has Been Hard

The Soviet newspaper Pravda published landing coordinates shortly after the mission — about 7°08' N, 64°22' W (≈7.13°N, 64.37°W) — but 1960s navigation and reporting were relatively imprecise. 'The error could have reached tens of kilometers,' says geochemist Alexander Basilevsky, who later selected Soviet landing sites. Luna 9 was built to work from a wide range of terrains, so its designers did not need pinpoint accuracy.

Modern Searches: LRO, Triangulation, and Machine Learning

When LRO arrived in 2009, researchers began hunting for tiny pieces of historic hardware in orbital imagery. LROC’s resolution is excellent (down to roughly 0.25–0.5 m/pixel in targeted images), but much of the candidate zone around Luna 9 is covered by images at about 1 m/pixel — borderline for spotting the small spherical capsule.

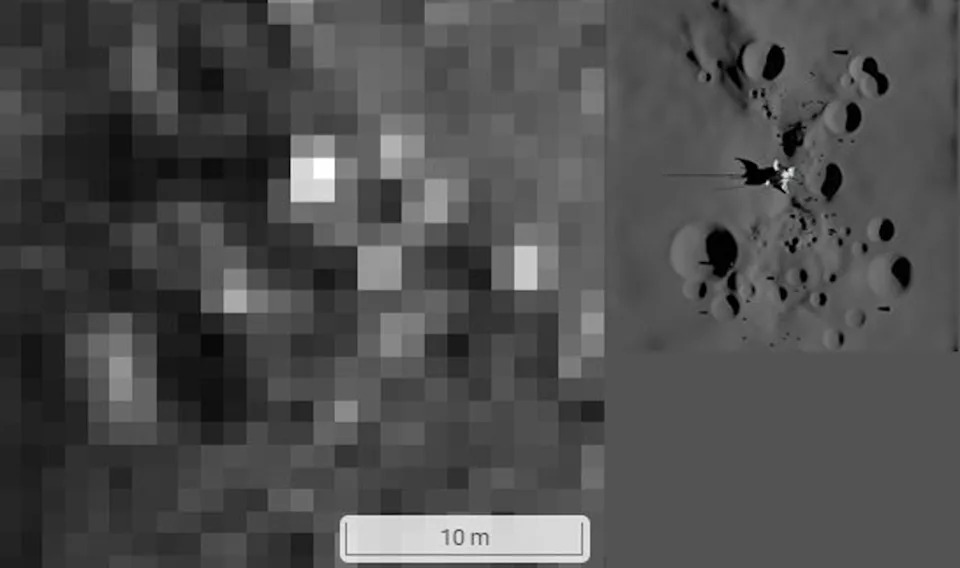

Vitaly Egorov, who previously identified the Soviet Mars 3 lander in Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter images, returned to the Luna 9 problem using crowdsourcing and triangulation of the original 1966 panoramic images. By matching distinctive panorama features (two distant hills, boulders, an ejecta streak) to topographic data from LRO's laser altimeter and drawing azimuth lines, Egorov identified a persuasive candidate at roughly 7.86159°N, 63.85562°W — about 25 km from the Soviet-reported coordinates. He cautions that the apparent object occupies only a few pixels and could be a natural rock.

Separately, a team led by Lewis Pinault at University College London adapted a machine-learning algorithm (originally trained to spot micrometeoroids) to search for human-made artifacts. After training on Apollo landing sites, the system successfully identified Luna 16 in test images and flagged several candidate anomalies within about five kilometers of Luna 9’s official coordinates. These machine-identified candidates do not all match Egorov’s location.

What Could Confirm a Discovery

Egorov shared his coordinates with Indian specialists planning a targeted imaging pass by Chandrayaan-2 in March 2026. Chandrayaan-2’s highest-resolution camera can reach about 0.25 m/pixel, which in principle could show the spherical central body as a distinct pixel and possibly resolve the four petal antennas. Both the machine-learning candidates and Egorov’s triangulated site will require directed high-resolution imaging and expert human analysis to confirm.

'Machine learning efficiently isolates statistically significant anomalies, while domain expertise remains essential for physical interpretation and validation,' Pinault's team notes in npj Space Exploration.

Science and Heritage

Finding Luna 9 is more than solving a historical mystery. Locating and studying surviving hardware offers a rare laboratory for understanding how materials change after decades exposed to the airless, radiation-bathed lunar environment. 'The most important thing is locating these artifacts to understand how materials change after decades of exposure to the lunar environment,' Basilevsky says.

As Chandrayaan-2 prepares for a targeted pass, researchers hope the tiny 'beach ball' that first touched the Moon will finally be found — and maybe one day visited by people retracing humanity’s earliest footprints on another world.

Help us improve.