2026 could be a landmark year for space: new wide‑field telescopes (NASA's Roman, ESA's PLATO and China's Xuntian) will begin unprecedented sky surveys to study exoplanets, dark matter and cosmic evolution. Human spaceflight milestones include NASA's Artemis II lunar flyby and India's Gaganyaan test flights, while robotic missions such as Japan's MMX and China's Chang'e 7 will probe planetary origins and lunar resources. International collaboration — exemplified by the SMILE space‑weather mission — remains strong even amid geopolitical competition.

2026: New Flagship Telescopes, Moon Crews and Global Science — Why This Year Will Be Pivotal for Space

In 2026, humanity expects a wave of ambitious missions that will reshape our view of the cosmos and accelerate human and robotic exploration beyond Earth. From galaxy‑surveying flagship telescopes to crewed lunar flybys and coordinated international probes, the year's launches could mark a turning point in how we study the universe and how nations cooperate — and compete — in space.

New Flagship Space Telescopes

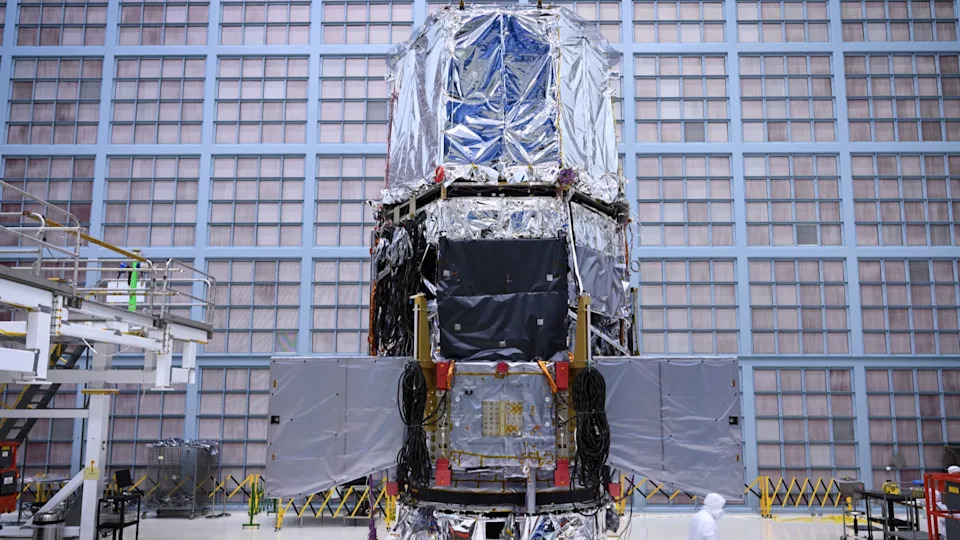

NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is the centerpiece of a new generation of wide‑field observatories. With a 300‑megapixel camera that images patches of sky roughly 100 times larger than Hubble's at comparable sharpness, Roman is optimized to survey vast areas quickly. In a five‑year primary mission it aims to discover hundreds of thousands of distant exoplanets via microlensing, map billions of galaxies across cosmic time, and probe dark matter and dark energy — phenomena that together account for about 95% of the universe's mass–energy budget. Roman also carries a coronagraph demonstrator to directly image exoplanets, a technology pathfinder for future life‑search missions like the proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory.

ESA's PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) is scheduled to launch on Ariane 6 in December 2026. Using an array of 26 cameras to monitor roughly 200,000 stars, PLATO will hunt for small, rocky planets in habitable zones while measuring stellar ages — crucial context for assessing planetary habitability.

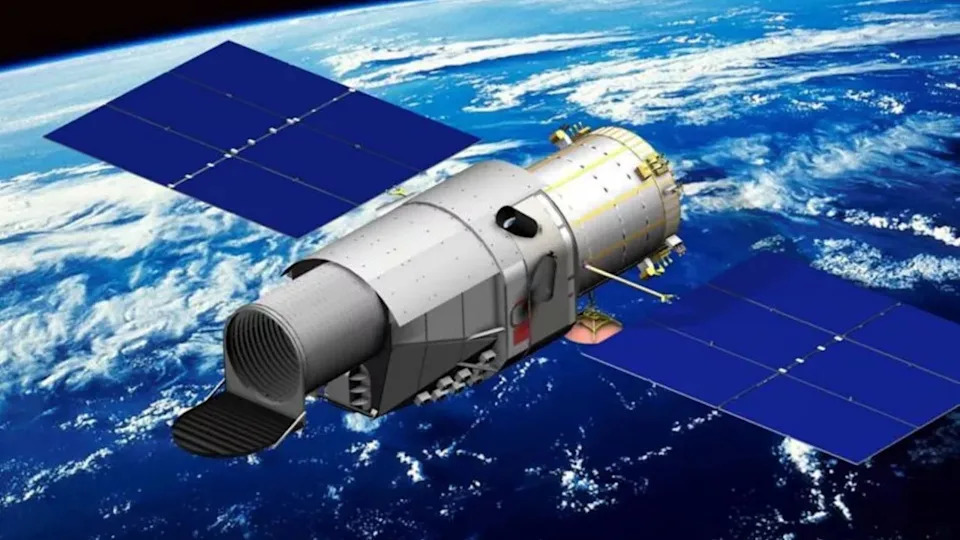

China's Xuntian Space Telescope (the Chinese Space Station Telescope), planned for late 2026, will deliver Hubble‑quality images over a field of view more than 300 times larger than Hubble's. Co‑orbiting with the Tiangong space station, Xuntian can be serviced and upgraded by astronauts, potentially extending its science lifetime by decades. Like Roman and PLATO, it will study dark matter, dark energy and the large‑scale structure of the universe.

On the ground, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will repeatedly scan the southern sky, complementing space telescopes by tracking transient events and the evolving universe. Together these facilities will let astronomers study both the present universe and its history on unprecedented scales.

Human Spaceflight: Return Beyond Low Earth Orbit

NASA's Artemis II, being prepared for a possible April 2026 launch, aims to send four astronauts on a roughly 10‑day crewed flight around the Moon and back — the first human trip beyond low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 (1972) if it flies as planned.

India's Gaganyaan program plans uncrewed test flights in 2026 as steps toward independent crewed missions. Success would make India the fourth nation to achieve human spaceflight autonomously — a major technological and symbolic milestone.

China will continue regular crewed missions to its Tiangong space station in 2026, building experience and infrastructure that feed its plans for future crewed lunar missions. Meanwhile, NASA increasingly depends on commercial partners to ferry astronauts to low Earth orbit so the agency can focus on deep‑space exploration.

Planetary Science and Lunar Resource Exploration

Japan's Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission, targeting a late‑2026 launch, will reach Mars and study its moons Phobos and Deimos for about three years. MMX plans to collect and return a Phobos surface sample to Earth by 2031, data that could resolve whether these moons are captured asteroids or debris from a giant impact.

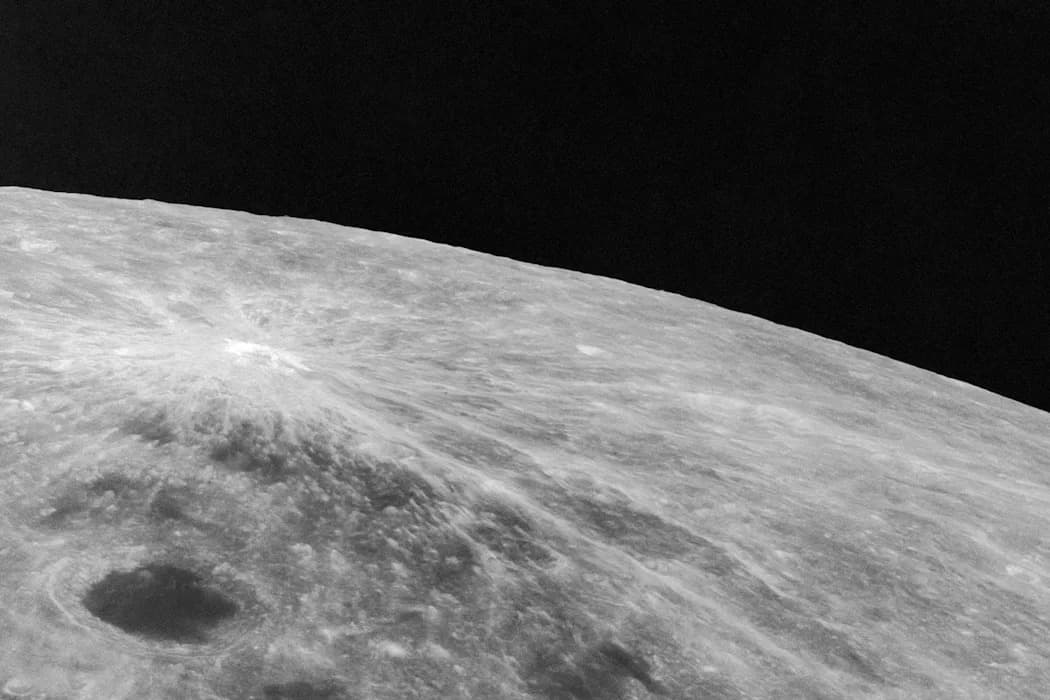

China's Chang'e 7, expected in mid‑2026, will explore the lunar south pole with an orbiter, lander, rover and a small flying hopper designed to access permanently shadowed craters. Those craters are prime targets because they may harbor water ice — a resource with major implications for sustained lunar presence and in‑space fuel production.

These missions show how planetary science, resource prospecting and future human activity are becoming more tightly linked.

Space Weather and International Cooperation

Recent powerful solar storms demonstrated how solar activity can disrupt aviation, communications and power systems on Earth. Understanding the Sun–Earth connection is therefore practical as well as scientific.

SMILE (Solar Wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer), a joint mission of the European Space Agency and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, is scheduled for spring 2026. SMILE will produce the first global images of how Earth's magnetic field responds to the continuous solar wind, improving forecasts of space weather that threaten satellites, navigation and ground infrastructure. Politically, SMILE is also a notable example of sustained Europe–China scientific collaboration amid broader geopolitical tensions.

What 2026 Will Mean

Collectively, the telescopes, crewed flights and robotic probes of 2026 reflect both cooperation and competition in space. Instruments and missions increasingly rely on international partnerships — for instrumentation, data sharing and scientific analysis — even as nations pursue independent capabilities and strategic objectives. For researchers and the public alike, 2026 promises an extraordinary year of discovery: new data on exoplanets and cosmic structure, advances in lunar and planetary science, and renewed human journeys beyond low Earth orbit.

Help us improve.