Artemis II, scheduled for early 2026, will send four astronauts on a lunar flyby to validate life-support and navigation systems and to signal a U.S. shift from symbolic firsts toward sustained, partnership-driven lunar presence. China’s state-led program emphasizes incremental capability and aims for a crewed landing by about 2030. As more actors converge near resource-rich regions like the south pole, interpreting the Outer Space Treaty’s "due regard" obligation becomes an immediate operational challenge. U.S. policy now emphasizes continuity, commercial participation, and shared norms to reduce uncertainty and enable cooperation.

Artemis II Signals A New U.S. Moon Strategy — Open Coalitions vs. China’s State-Led Program

When Apollo 13 swung around the moon in April 1970, more than 40 million people worldwide watched as the United States turned a potential disaster into a dramatic rescue. An oxygen-tank explosion transformed an intended landing into a fight for survival, and the three astronauts used lunar gravity to sling themselves back to Earth — a moment of technical drama and geopolitical signaling.

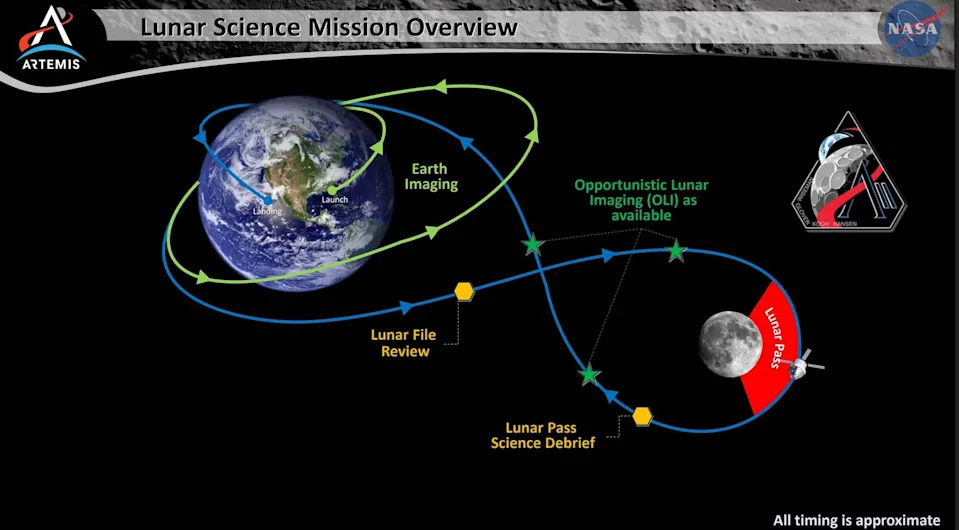

More than half a century later, NASA's Artemis II will again send humans around the moon, currently scheduled for February 2026. The mission — a four-person crewed flyby that will validate life-support and navigation systems — is modest in technical terms but significant strategically. It signals a shift from symbolic firsts toward building a sustained presence, shaped by international partnerships and commercial participation.

From Two-Player Race To Multipolar Activity

The Cold War space race was primarily a bilateral contest between the United States and the Soviet Union. Today, many more nations and private companies are active around the moon. This changes the nature of competition: success increasingly depends on repeated presence, interoperable systems, and shared norms rather than one-off headlines.

Two Different Approaches

China has developed a centrally directed, well-resourced lunar program focused on stepwise capability and long-term presence. Its robotic achievements include far-side landings and sample returns, and Beijing has stated ambitions for a crewed lunar landing by around 2030. China’s model is characterized by tight state control and selective international partnership.

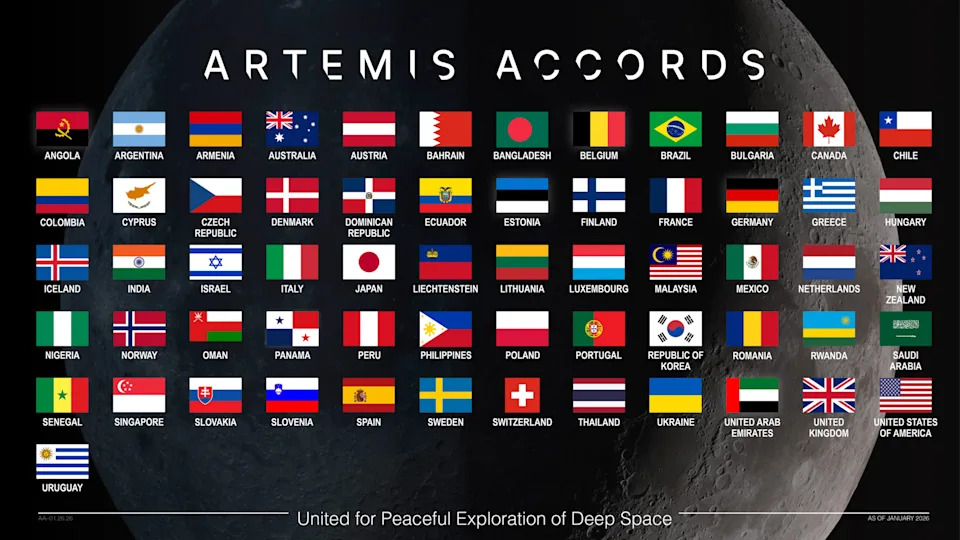

By contrast, the U.S. Artemis program is intentionally open to international and commercial partners. The goal is to create a predictable framework for exploration, surface operations, and responsible resource use so that allies and private firms can plan, invest, and operate within shared expectations.

Why Crew Matters

Human missions beyond low Earth orbit carry different political and technical implications than robotic probes. Crewed lunar flights require sustained political commitment, multi-year funding stability, and reliable systems that partners can depend on. Artemis II is a bridge to Artemis III, currently targeted for a crewed landing near the lunar south pole around 2028. A credible sequence of human missions signals a shift from experimentation toward sustained operations.

Law, Norms, And Operations

International law already matters. Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty obliges states to act with "due regard" for the interests of others and to avoid harmful interference. As activity intensifies — particularly near resource-rich regions such as the lunar south pole — interpreting "due regard" becomes an immediate operational question: does it mean merely not colliding, or does it require active coordination?

Historical parallels on Earth, especially in maritime disputes, show how vague legal standards can produce conflict when traffic, resource extraction, and military activity increase. The same risk applies to lunar operations unless states and commercial actors develop common practices and transparent coordination mechanisms.

Policy Momentum

U.S. policy has begun to reflect this long-term view. Recent government reports and a new executive order emphasize federal support for continued lunar activity, commercial involvement, and interagency coordination. Likewise, assessments such as the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission's 2025 report frame human spaceflight and deep-space infrastructure as elements of sustained strategic competition rather than one-off achievements.

What Leadership Looks Like

Competition will shape the pace and character of lunar activity, but leadership will depend on reducing uncertainty, enabling cooperation, and converting ambition into stable operating practices. Artemis II will not settle the future of the moon, but it is a clear demonstration of the American model: coalition-building, transparency, and efforts to establish shared expectations for how activities on and around the moon will be conducted.

Looking Ahead: If the U.S. approach remains consistent and partners continue to rally around interoperable rules and commercial opportunities, that model could help determine how the next era of lunar — and eventually Martian — exploration unfolds.

Help us improve.