An international team led by Rice University developed a copper–aluminum layered double hydroxide (LDH) filter that captures PFAS roughly 100 times faster than commercial carbon filters and, the authors say, adsorbs PFAS up to 1,000 times better than other materials. The LDH binds PFAS quickly; heating combined with calcium carbonate regenerates the filter and strips fluorine from PFOA, producing a fluorine–calcium residue the team suggests can be landfilled safely. Lab tests with river, tap and wastewater samples show promise, but larger-scale testing and independent validation are still needed.

Record-Breaking Filter Destroys PFAS 100x Faster Than Carbon, Researchers Say

An international team of scientists has developed a novel filtration material that captures and helps destroy persistent per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) far faster than conventional carbon filters. Led by engineer Youngkun Chung of Rice University, the researchers report a layered double hydroxide (LDH) compound that adsorbs PFAS at rates roughly 100 times quicker than commercial carbon filters and, according to the team, binds PFAS up to 1,000 times more effectively than other tested materials.

Why PFAS Matter

PFAS are synthetic chemicals introduced in the 1940s that resist water, grease and heat. They are used in products such as rainwear, upholstery, non-stick cookware, food packaging and firefighting foams. The carbon–fluorine bonds that characterize many PFAS make them exceptionally persistent in the environment; some variants are expected to take thousands of years to break down. Several widely studied PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, have been linked to cancer, cardiovascular disease, reproductive harm and birth defects, and more than 12,000 PFAS variants remain in use with largely unknown health effects.

How the New LDH Filter Works

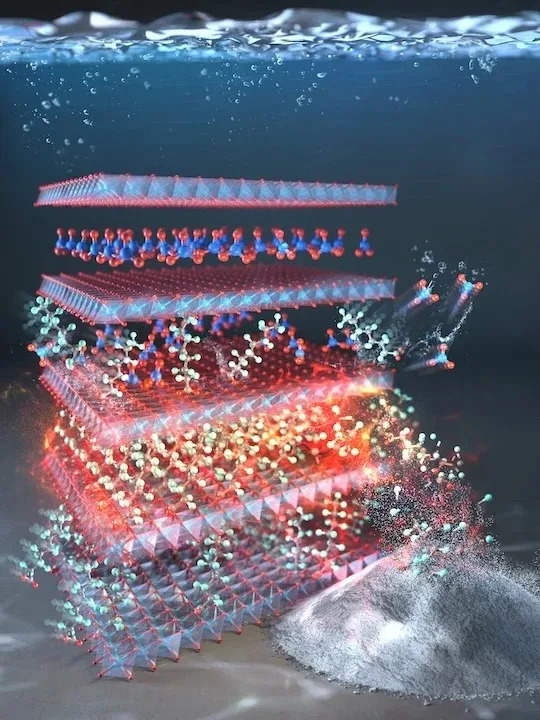

The LDH material is formed from stacked layers of copper and aluminum combined with nitrate. The material's slight charge imbalance attracts and tightly binds PFOA and similar PFAS molecules, delivering rapid adsorption measured in minutes. Chung and colleagues report that this structural and chemical arrangement is the key to both the speed and high capacity observed in laboratory tests.

When the LDH becomes saturated, the researchers regenerate it by applying heat and adding calcium carbonate. This treatment cleans the adsorbent for reuse and chemically strips fluorine from captured PFOA, effectively breaking down the molecule's fluorinated backbone. According to Rice engineer Michael Wong, this process yields a fluorine–calcium residue that the team says can be disposed of in landfill safely.

Tests, Promise and Caveats

The LDH filter performed well in laboratory experiments using PFAS-contaminated water from rivers, household taps and wastewater treatment plants, with particularly strong results against PFOA. The work is published in the journal Advanced Materials.

While the results are promising, the researchers emphasize that the technology is at an early, laboratory stage. Key steps remain before widescale deployment, including testing across the many PFAS variants, pilot-scale demonstrations, long-term durability and independent assessment of the treated waste stream and disposal strategy. If those challenges can be addressed, the LDH approach could offer a faster, potentially reusable option for treating PFAS-contaminated waters.

Note: Claims about adsorption capacity, destruction efficiency and waste disposal are those reported by the research team and will require further peer review and field-scale validation.

Help us improve.