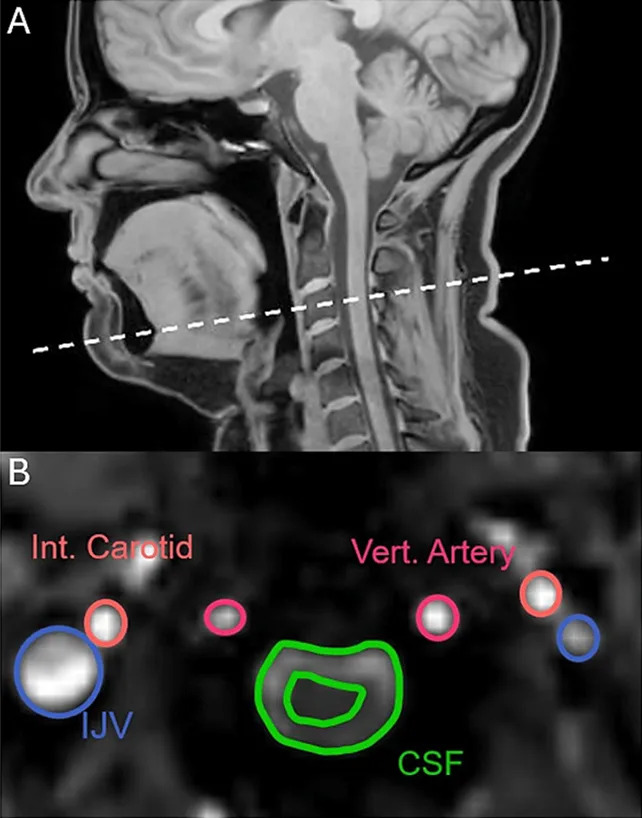

Researchers at the University of New South Wales used MRI to scan 22 volunteers while they yawned, took deep breaths, suppressed yawns and breathed normally. The scans showed yawns displaced cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) away from the brain — a pattern not seen with deep breaths — while both actions increased venous outflow. Carotid arterial inflow rose by roughly one-third during the early stage of yawns, and individuals displayed consistent, innate yawning patterns. The study is a bioRxiv preprint and has not yet been peer-reviewed.

MRI Study Finds Yawns Push Protective Brain Fluid Away — What That Might Mean

New MRI evidence suggests yawning does more than look contagious: it changes how the fluid that cushions the brain moves. A small imaging study from the University of New South Wales found that yawns — unlike deep breaths — appear to displace cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) away from the brain, while both behaviors increase venous outflow.

How the Study Was Done

The research team scanned the heads and necks of 22 healthy volunteers using MRI while participants were instructed to yawn, take deep breaths, suppress yawns and breathe normally. The researchers compared the mechanical and hemodynamic effects of yawning versus deep inhalations.

Key Findings

CSF Movement: Yawns produced a detectable displacement of cerebrospinal fluid away from the brain — a pattern not seen with deep breaths.

Blood Flow: Both yawns and deep breaths increased venous outflow from the brain, which can create space for fresh arterial blood to enter. During the early phase of a yawn, carotid arterial inflow surged by roughly one-third.

Individual Patterns: Each participant displayed consistent, individual-specific yawning patterns across repeated yawns, supporting the idea of a central pattern generator — an innate neural program that shapes yawning behavior.

"The yawn was triggering a movement of the CSF in the opposite direction than during a deep breath," neuroscientist Adam Martinac told New Scientist. "And we're just sitting there like, whoa, we definitely didn't expect that."

Possible Implications

The authors suggest several hypotheses. One possibility is that yawning helps clear metabolic waste or redistribute CSF in a way that supports brain homeostasis. Another is that yawning contributes to brain thermoregulation (cooling). The observed surge in carotid inflow also raises the possibility of multiple, concurrent physiological roles for yawning.

Limitations and Cautions

The effect was not observed in every participant and was detected less frequently in men; the researchers caution this could reflect interference from the MRI scanner rather than a true sex difference. The study involved a modest sample (22 people) and the findings are reported as a bioRxiv preprint, meaning the work has not yet been peer reviewed.

Bottom Line

The study provides intriguing evidence that yawning can alter CSF dynamics and cerebral blood flow in ways that differ from deep breathing. While the results offer clues about why yawning is conserved across many species, further research with larger, peer-reviewed studies is needed to determine whether yawning has a protective or regulatory role for the brain.

Availability: Results are currently available as a preprint on bioRxiv and should be interpreted cautiously until peer review is complete.

Help us improve.