Researchers from an international team report that leftover "zombie" fragments of SARS‑CoV‑2 can home in on and damage specific immune cells, such as dendritic cells and CD4+/CD8+ T cells, potentially contributing to long COVID symptoms. The fragments preferentially attack cells with spiky membrane curvature, offering a new mechanism for observed immune depletion. Analyses indicate Omicron produces a wider range of fragments but fewer that are cytotoxic to these immune cells. The study appears in PNAS and underscores ongoing risks from COVID‑19.

'Zombie' Coronavirus Fragments May Destroy Immune Cells — A Possible Driver Of Long COVID

Fragments of SARS‑CoV‑2 that remain after the virus is broken down in the body — described by researchers as "zombie" viral remnants — may not only drive inflammation in long COVID but also directly damage and kill key immune cells.

What The Study Found

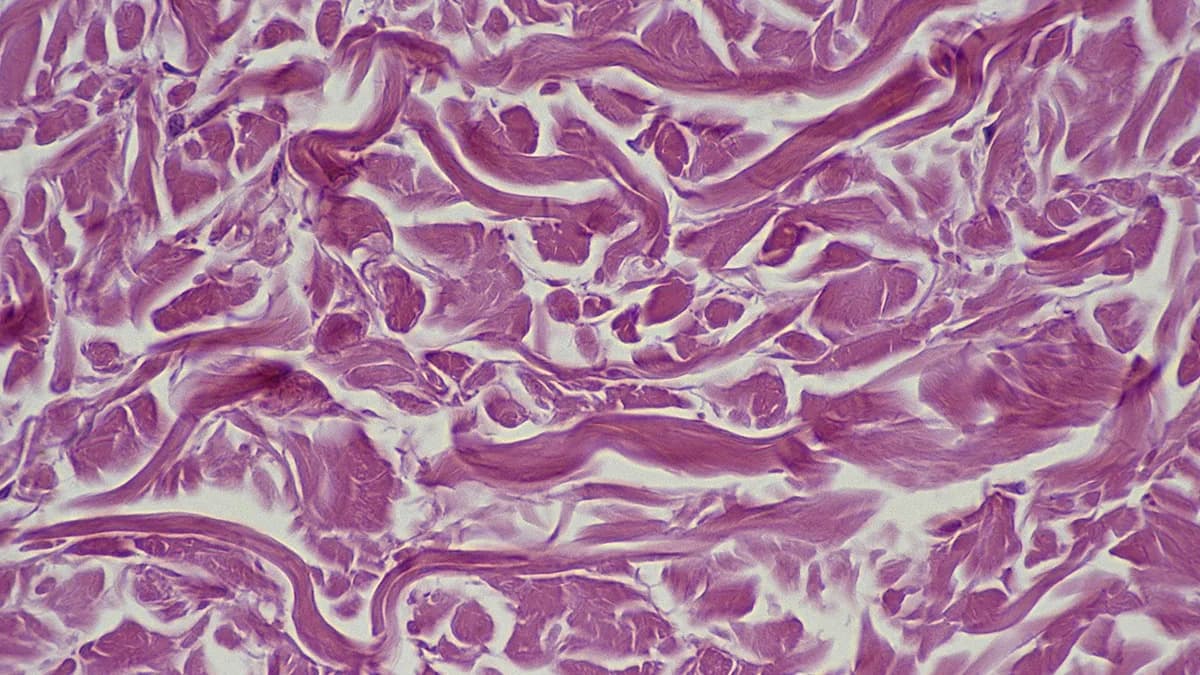

An international team of more than 30 authors reports that when the virus is degraded inside people, leftover protein pieces can home in on and harm specific immune-cell types. The fragments appear to recognize a particular membrane curvature, making cells with spiky or highly projected surfaces especially vulnerable.

Vulnerable Cells: These "spiky" cells include dendritic cells, which act as early-warning sentinels that detect viruses and activate broader immune responses, as well as CD8+ and CD4+ T cells that destroy infected cells. Earlier research had observed depletion of these T cells in some patients, and the new findings provide a plausible mechanism that could help explain persistent immune dysfunction in long COVID.

"These fragments recognize a particular curvature on cell membranes," says bioengineer Gerard Wong of the University of California, Los Angeles. "Cells that are spiky, star-shaped, or have many projections tend to be selectively suppressed."

Variant Differences And Implications

The authors compared fragments produced by different variants and found that the Omicron variant breaks down into a wider variety of protein fragments than earlier strains. Importantly, many of Omicron's spike fragments were less capable of killing these crucial immune cells, which may help explain why Omicron infections tended to deplete immunity less severely despite high transmissibility.

"We need to know what residual viral material does to us both during acute infection and afterward," Wong adds. "These fragments open up a whole new set of mechanisms to investigate."

Public-Health Context

Despite some narratives that the pandemic is over, COVID‑19 continues to cause substantial harm: roughly 100,000 deaths per year in the United States and many more cases of long-term disability. As of 2024, an estimated up to 17 million people in the U.S. were living with long COVID.

Clinicians warn that repeat infections may increase the risk of long COVID in both children and adults. "One of the clearest messages I give patients, families, and physicians about vaccination is this: More vaccines mean fewer infections, and fewer infections should mean less long COVID," said pediatrician Ravi Jhaveri of Lurie Children's Hospital in Chicago.

Study Source: The research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Help us improve.