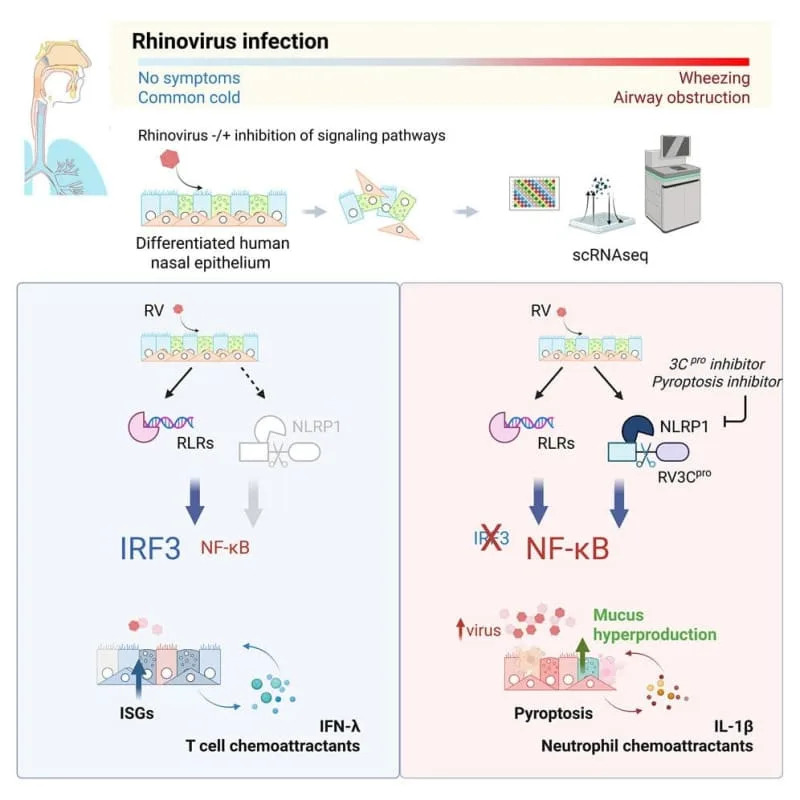

The severity of a cold often depends less on the virus and more on how quickly your nasal lining responds. Yale researchers used lab-grown human nasal tissue to show that a rapid interferon response can contain rhinovirus, while delayed signaling allows viral spread, tissue damage, and increased mucus and inflammation. The work points to therapies that could boost early antiviral alarms or limit later symptom-driving pathways—especially important for people with asthma.

Why Some Colds Knock You Down: Your Nasal Lining's Early Interferon Alarm Matters

A common cold can feel trivial—until it isn't. One morning you feel fine; the next you wake up congested, exhausted and foggy. New research from Yale suggests that how quickly your nasal lining sounds its alarm may determine whether a rhinovirus infection stays mild or becomes a full-blown cold.

Key Findings

Using lab-grown human nasal tissue, researchers found that a rapid interferon response in the nasal epithelium can halt rhinovirus spread. When that early antiviral alarm is delayed or blocked, the virus infects many more cells, damages tissue and can trigger increased mucus production and inflammation—responses that underlie the symptoms you know as a cold and may worsen breathing problems in people with asthma.

How the Study Was Done

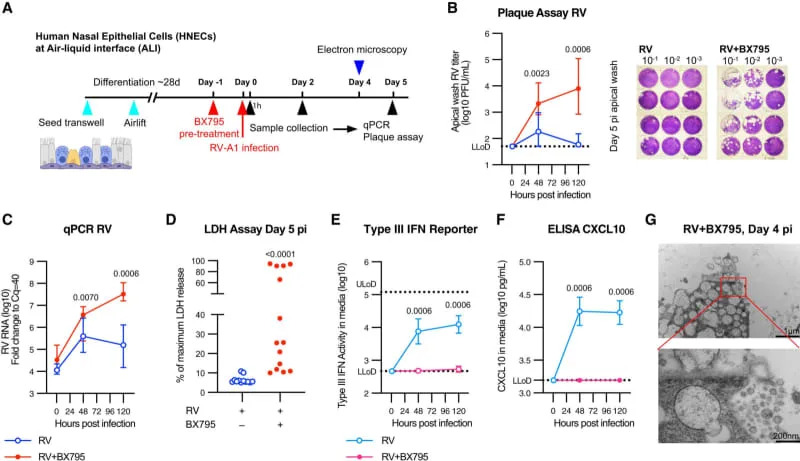

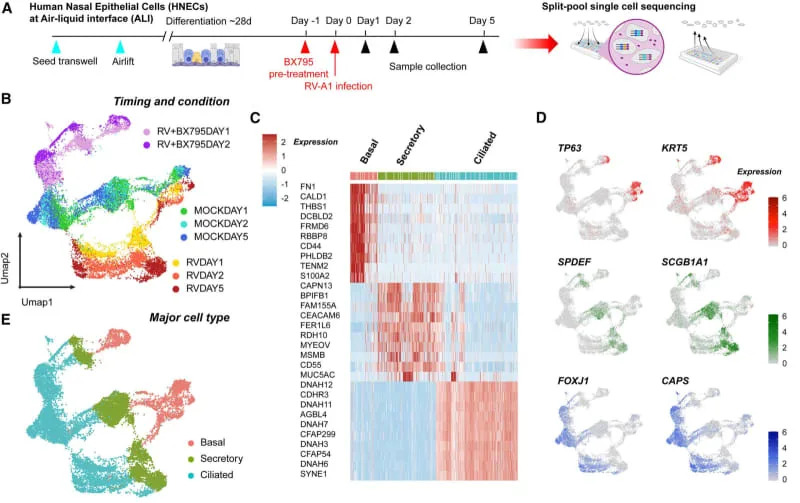

The team began with human nasal stem cells and cultured them at an air–liquid interface for about four weeks so the cells matured into tissue containing the major cell types found in human nasal passages, including mucus-producing cells and ciliated cells that clear mucus. Because rhinoviruses cause disease in humans but not in many animal models, these organotypic human tissues are especially useful for studying infection.

What the Tissue Showed

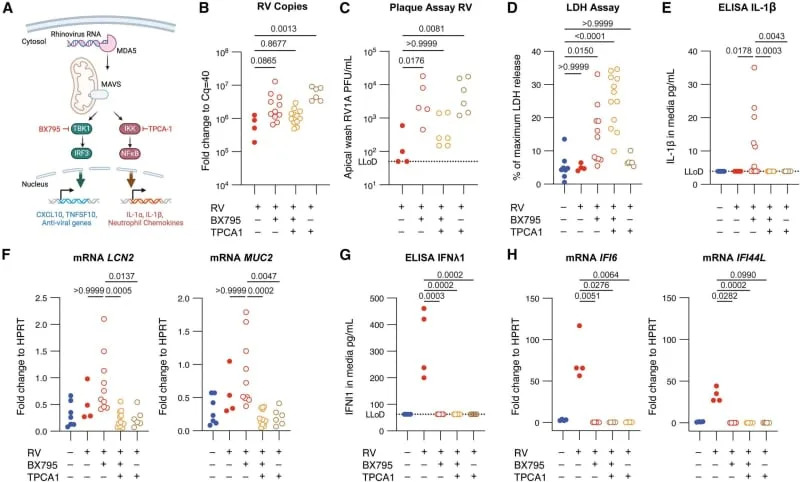

When rhinovirus infects nasal cells, those cells communicate using interferons—proteins that warn nearby cells and induce antiviral defenses. The laboratory tissue mounted a potent defense even without recruited immune cells: a fast interferon wave contained infection across many cells. Experimentally blocking interferon signaling dramatically increased viral replication, caused tissue damage and, in some organoids, cell death.

“Our experiments show how critical and effective a rapid interferon response is in controlling rhinovirus infection, even without any cells of the immune system present,”

— Bao Wang, First Author, Yale School of Medicine

Downstream Responses and Clinical Relevance

If the early interferon response fails, the tissue shifts into other sensing pathways that drive excessive mucus production and inflammation. Those later responses may initially be protective but can cause the congestion, cough and breathing difficulties that make colds miserable and can be especially hazardous for people with asthma and chronic lung disease.

Implications and Limitations

The findings point to two therapeutic strategies: 1) bolster the rapid interferon alarm in the nasal lining to stop infection early; and 2) modulate later symptom-driving pathways (mucus and inflammation) to reduce suffering while preserving antiviral defenses. The authors caution that their organoid model contains fewer cell types than a living nose; in a real infection, many immune cells and environmental factors will also shape outcomes. Future research will need to explain why some people mount a fast interferon response while others do not.

Study source: Findings are available online in Cell Press Blue.

Help us improve.