UCR researchers used single-cell RNA sequencing in mice to show that Toxoplasma gondii cysts contain multiple parasite subtypes rather than a single dormant form. Up to five distinct parasite states were identified; some can approach reactivation stages after just days in culture. Cysts from chronically infected mice (28 days) showed greater subtype diversity than during the acute stage. The work, published in Nature Communications, suggests new, more targeted approaches will be needed to prevent reactivation and treat chronic toxoplasmosis.

Brain Parasite Thought Dormant Shows Multiple Active Forms — New Study Changes How We Fight Toxoplasma

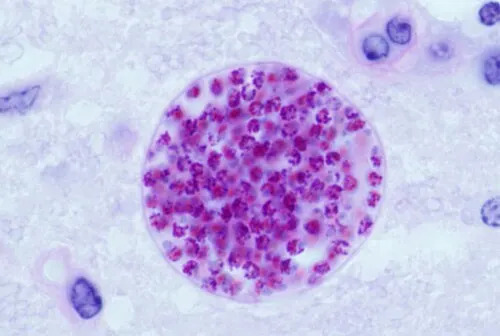

Researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) report that the parasite Toxoplasma gondii — which infects more than a third of people worldwide — may be far less uniformly dormant inside brain cysts than scientists previously believed.

Using single-cell RNA sequencing in mice, the UCR team found several distinct parasite subtypes coexisting within individual cysts. Rather than a single, inactive form, cysts contained up to five different parasite states that grow and develop at different rates. Some subtypes, after only a few days in laboratory culture, approached molecular stages linked to renewed activity.

What the Study Found

In experiments comparing acute infection and chronic infection (mice infected for 28 days), cysts from chronically infected brains showed greater subtype diversity than those from the early stage of infection. During the first week after infection, parasites tended to move toward faster-growing stages; later they shifted into slower-growing forms and variants that appear specialized to maintain the cyst.

"We found the cyst is not just a quiet hiding place — it's an active hub with different parasite types geared toward survival, spread, or reactivation," said biomedical researcher Emma Wilson of UCR.

Why This Matters

Toxoplasmosis — the disease caused by T. gondii — is usually symptomless in healthy people, but it can cause serious complications for people with weakened immune systems, including seizures and vision problems. Current antiparasitic drugs target active, replicating parasites; dormant cyst stages are much harder to clear. Identifying multiple subtypes within cysts helps explain why some drug-development efforts have struggled and points to more precise targets for preventing reactivation.

The authors argue that cyst maturation is not a simple linear process but a dynamic environment with different parasite roles. The study, published in Nature Communications, calls for updated models of the Toxoplasma life cycle and suggests that therapies aimed specifically at cyst-resident subtypes may be necessary to fully control chronic infection.

Limitations and Next Steps

These findings derive from mouse models and laboratory culture experiments; translating them to human infections will require additional research. Future studies should test whether the same subtype diversity exists in human cysts, determine which subtypes are most likely to reactivate, and screen for drugs that target those forms.

Bottom line: Toxoplasma cysts appear to be biologically active and heterogeneous, not uniformly dormant. This new view could reshape strategies to prevent reactivation and eliminate chronic infection.

Help us improve.