New START, the 15‑year bilateral treaty limiting deployed US and Russian strategic nuclear forces, is set to lapse, removing legally binding caps and active verification. With verification suspended and relations strained after the Ukraine war, the treaty’s expiry raises the risk of weapon uploads or a fragile tacit status quo. Rose Gottemoeller — the lead US negotiator for New START — argues nuclear talks can be insulated from wider crises, advises deliberate engagement with China, and warns that new technologies like AI bring both verification benefits and destabilising risks.

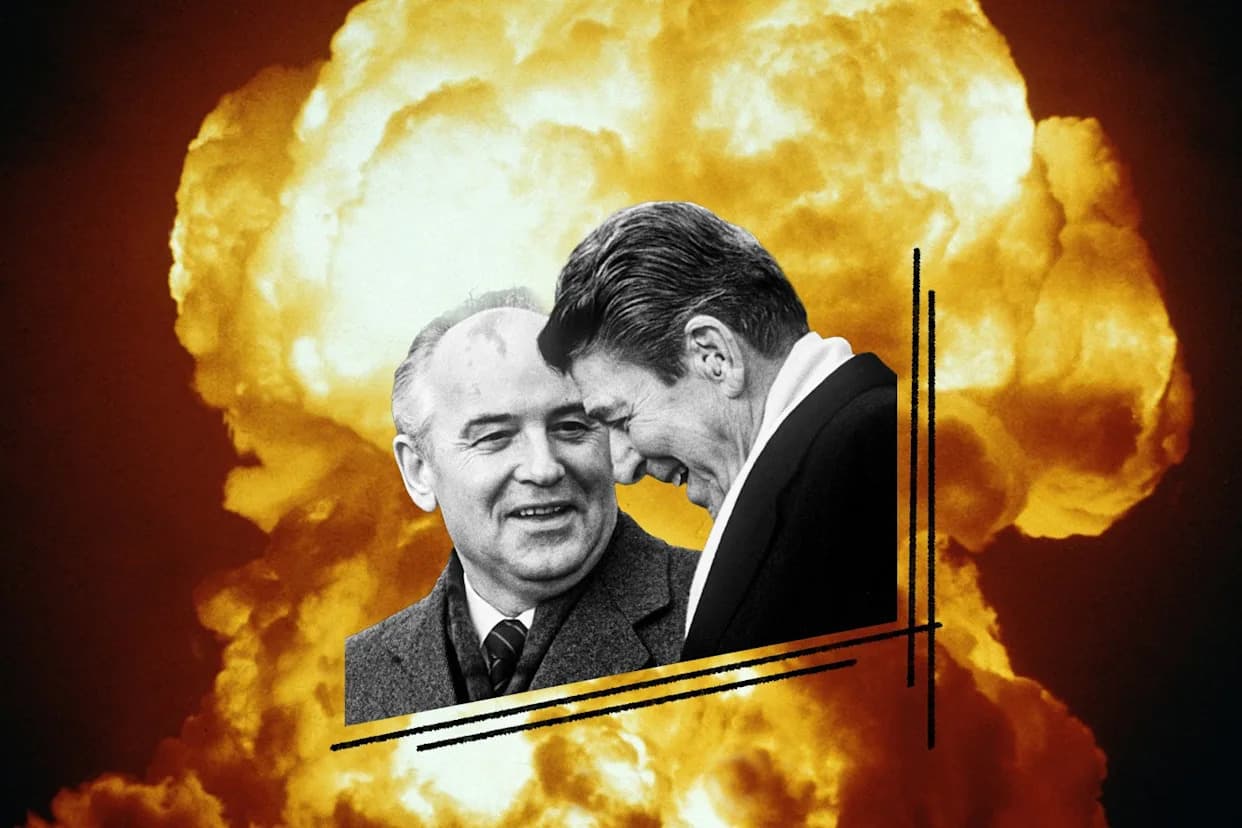

Lapse of New START: Could a New US–Russia Nuclear Arms Race Follow?

New START, the 15‑year‑old bilateral treaty that capped deployed strategic nuclear forces between the United States and Russia, is set to lapse. As the last remaining major arms‑control pact between the world’s two largest nuclear powers, its expiry removes the principal legal limits on deployed warheads and delivery systems and raises fresh risks for strategic stability.

What New START Did

Signed in 2010 and entered into force in 2011, New START capped each side’s deployed strategic offensive forces at 1,550 warheads and 700 delivery vehicles (intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine‑launched ballistic missiles and strategic bombers). Those numerical ceilings held for about 15 years and were reinforced by verification measures that increased transparency and trust.

Why It’s Lapsing

Renewal or replacement of New START has been complicated by the sharp deterioration in US‑Russia relations following Russia’s full‑scale invasion of Ukraine. In February 2023, the Kremlin announced it would suspend some treaty verification measures while asserting it would continue to respect numerical limits. The five‑year extension agreed by Presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin in 2021 provided temporary breathing room, but with the extension ending and verification dormant, neither side is currently bound by the treaty’s limits unless a new political or legal arrangement is reached.

Short‑Term Options And Risks

With the treaty no longer in force, several outcomes are possible:

- Rapid “Uploading.” One or both sides could increase the number of warheads mounted on deployed delivery systems, reversing the long post‑Cold War trend of limits on deployed forces.

- Tacit Restraint. Each side could opt to keep forces at roughly current levels without a public announcement, effectively maintaining the status quo by mutual restraint.

- Escalating Competition. If mistrust grows, the absence of verification could accelerate qualitative and quantitative arms competition, including new delivery systems or expanded arsenals.

China, New Technologies, And A Changing Landscape

The strategic picture today is more complicated than in 2010. The United States and Russia still account for the majority of global nuclear warheads — each nation possesses roughly several thousand total warheads and deploys about 1,550 strategic warheads — while China’s arsenal is estimated to be growing (commonly cited at roughly 600 warheads, though estimates vary). That rise creates pressure to consider Beijing’s role in future arms‑control conversations, but experts caution against forcing China prematurely into a trilateral deal given the current numerical asymmetry and limited history of nuclear negotiation between Washington and Beijing.

Emerging technologies add both opportunity and risk. Advances in verification tools, remote sensing and data analysis could strengthen monitoring and transparency. At the same time, hypersonic weapons, improved missile mobility, and artificial intelligence applied to command, control, and targeting could erode first‑strike stability and complicate deterrence. Many strategists emphasize preserving human judgment in nuclear decision‑making as a key safeguard.

Is Diplomacy Still Possible?

Rose Gottemoeller, the chief US negotiator for New START, argues that nuclear diplomacy has historically been insulated from other bilateral crises and that the existential character of nuclear weapons makes them worth talking about even when other relations are frozen. She notes precedents from the Cold War when arms talks continued despite severe disagreements on other issues.

At the same time, practical barriers are real: deteriorated political relations, the suspension of verification, and the Ukraine war make immediate progress difficult. Gottemoeller recommends a pragmatic, phased approach: retain or re‑establish transparency where possible, engage China constructively to clarify intentions rather than rushing it into a three‑party ceiling, and use technological advances to improve verification while guarding against destabilising uses of AI and novel delivery systems.

Bottom Line

The lapse of New START raises meaningful short‑term risks of renewed competition, but it does not make an arms race inevitable. History shows that dedicated political will and careful diplomatic design can recreate constraints and verification frameworks even in difficult times. The immediate challenge is whether Washington, Moscow — and increasingly Beijing — can find the political space to recommit to measures that reduce the risk of miscalculation and uncontrolled escalation.

Note: This article synthesises an interview with Rose Gottemoeller and public reporting on New START. Numbers for arsenals are approximate and based on publicly available estimates.

Help us improve.