Forty years after the Reykjavik summit, the vision of a world without nuclear weapons remains unrealized, but the talks reshaped arms control. Reykjavik’s momentum helped produce the INF and START I treaties and contributed to steep reductions from Cold War highs. Today the arms‑control framework is fraying, New START faces possible expiration in February 2026, and China’s rapid buildup complicates any return to bilateral limits — yet 2026 treaty reviews offer a chance to renew action.

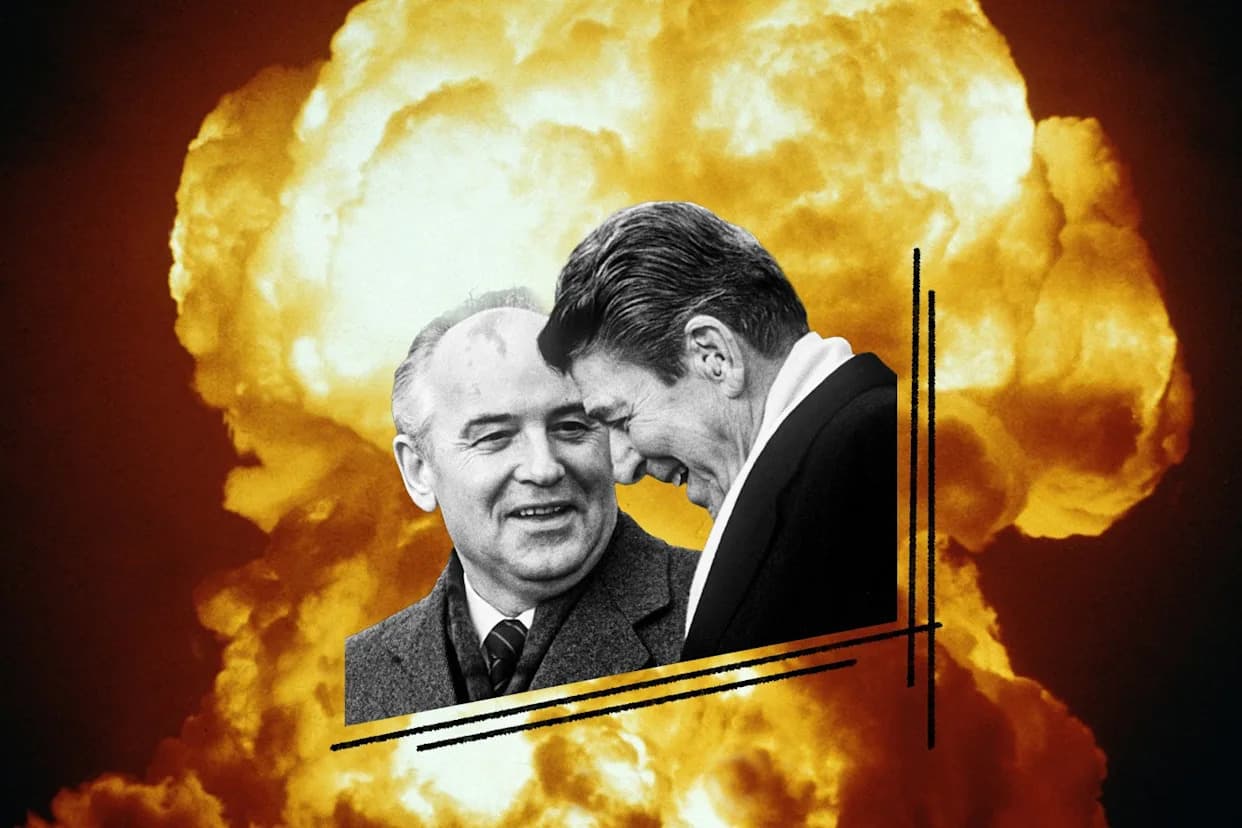

Reykjavik at 40: How a Near‑Miss on Zero Nukes Shaped — and Failed — Arms Control

In October 1986, a remarkable diplomatic moment briefly made the idea of a nuclear‑free world seem possible. At the Reykjavik summit, U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev pressed beyond Cold War convention, exploring dramatic reductions — and even the eventual elimination — of nuclear arsenals. Though the talks collapsed at the last hour, Reykjavik reshaped arms‑control thinking for decades to come.

Reykjavik And Its Unlikely Promise

The Reykjavik meeting began as a routine pre‑summit but turned into an intense 48 hours of negotiation. Delegations worked late into the night — famously using a bathtub with a door as an improvised desk — drafting proposals that included a 50% cut in strategic weapons and an eventual goal of abolishing nuclear arms. The summit’s collapse ultimately hinged on the U.S. Strategic Defense Initiative ("Star Wars") and deep mistrust over missile‑defense technology.

“Reykjavik cemented the idea that nuclear disarmament is something we need to aspire to,” said Nick Ritchie, professor of international security.

What Reykjavik Actually Achieved

Although it did not yield an immediate treaty, Reykjavik set in motion a series of agreements that substantially reduced Cold War arsenals. The Intermediate‑Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty (1987) and START I (1991) grew directly from the summit’s momentum. Over the next decades, additional measures — including work toward a Comprehensive Nuclear‑Test‑Ban — helped cut deployed strategic warheads from Cold War peaks.

To put the scale in context: global nuclear stockpiles once approached roughly 70,000 warheads at the Cold War high, with each superpower fielding thousands. Today, total global inventories are estimated at about 12,400 warheads, and under the New START framework the limit for deployed strategic warheads is 1,550 per side.

Where Momentum Broke Down

Not all promising initiatives survived. START II, designed in the early 1990s to eliminate destabilizing MIRVed (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle) ICBMs, never entered into force — leaving dangerously flexible and destabilizing systems intact. Over time, the arms‑control architecture frayed: the INF Treaty and earlier START agreements have expired or been suspended, and New START faces potential expiration in February 2026 despite a Russian offer of a one‑year extension.

Today’s Multipolar Challenges

Reykjavik was a product of a largely bipolar world. Today's landscape is more complex: China is rapidly expanding its arsenal (estimates suggest it is adding roughly 100 warheads per year), and other nuclear actors complicate any return to strictly bilateral bargaining. At the same time, political polarization, erosion of norms, and technological change (including missile defenses and new delivery modes) make broad disarmament harder to negotiate.

Deterrence, Disarmament, And Practical Steps

Experts caution that deterrence remains central to national security doctrine, but they debate its long‑term wisdom. Some advocates recommend maintaining minimal, secure deterrent forces while investing more in conventional capabilities and confidence‑building measures to reduce incentives for escalation. The Reykjavik story suggests radical reductions are politically imaginable when leaders prioritize crisis avoidance and find trusted negotiating settings.

Why Reykjavik Still Matters

Four decades on, Reykjavik’s lesson is twofold: bold leadership can expand the realm of the possible, but technical and political details can scuttle even the most promising bargains. With major treaty review conferences for the Nuclear Non‑Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) scheduled for 2026, policymakers have concrete opportunities to revive arms‑control momentum — if they learn from Reykjavik’s successes and failures.

“Two presidents recognized that devoting huge resources to weapons capable of ending civilization was unsustainable,” said Florian Eblenkamp of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. “Reykjavik proves that sanity can return.”

Whether today’s leaders will seize analogous moments remains uncertain. But Reykjavik’s mix of aspiration, improvisation, and practical treaty outcomes offers a blueprint for how far diplomacy can go — and how much depends on trust, technical detail, and political will.

Help us improve.