New research shows lung tumors can innervate the vagus nerve and send signals to the brainstem (the nucleus tractus solitarius). The brain responds by activating the sympathetic nervous system, releasing noradrenaline that binds β2‑adrenergic receptors on macrophages and reprograms them into an immunosuppressive state. This suppresses T cell activity and protects the tumor. Interrupting the brain–tumor circuit restored antitumor immunity in mice, but translating the findings to human therapies will take more work.

Lung Tumors Hijack Vagal Nerves and Turn the Brain Into an Immunity Brake

For decades cancer has been framed as a local problem of runaway cell growth. New research, however, reveals that lung tumors can reach beyond their local environment: they grow into vagal nerves and co‑opt a brain circuit that actively suppresses immune attacks on the tumor.

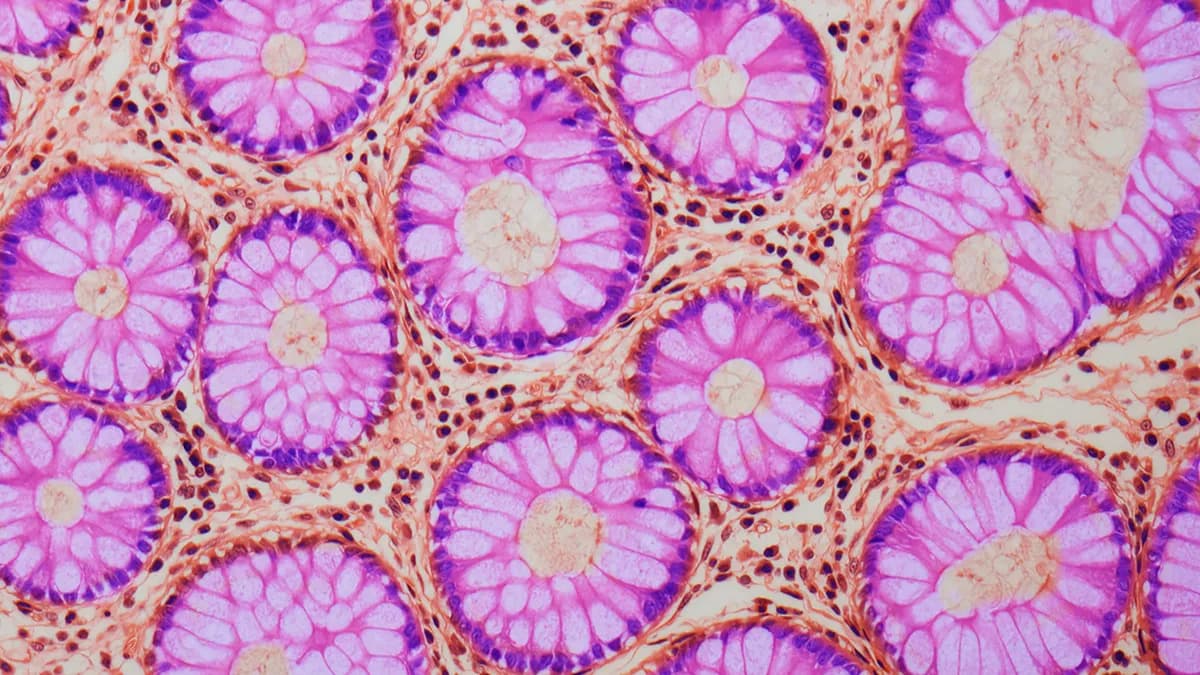

Researchers led by Chengcheng Jin (University of Pennsylvania) and colleagues found in mice that lung tumors innervate the vagus nerve and engage a specialized population of sensory neurons that relay signals to the brain. The team identified the same pathway in human samples, suggesting the circuit may be conserved across species.

How the Brain–Tumor Circuit Works

Innervated tumors send intense signals to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brainstem, a region that normally helps regulate autonomic functions such as blood pressure, heart rate and digestion. The tumor-driven signal hijacks this regulatory system and activates the sympathetic nervous system.

Activation of the sympathetic response causes local release of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) at the tumor site. That chemical binds to β2‑adrenergic receptors on macrophages—frontline immune cells responsible for detecting and clearing threats. When these receptors are engaged, the macrophages are reprogrammed into an immunosuppressive state.

Rewired macrophages secrete factors that act like a "do not disturb" signal to other immune cells. The shielded microenvironment weakens T cells: they become less active, stop proliferating and fail to recognize or kill tumor cells. In effect, the tumor uses the brain as an accomplice to create a protective, immune‑cold niche.

"The authors characterized an entire bidirectional tumor‑neural pathway that promotes tumor growth, with huge relevance to human health," says Catherine Dulac, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, who was not involved in the study.

Therapeutic Implications and Cautions

By mapping the pathway from lung to brain and back, the team identified multiple intervention points. In mice, disrupting elements of the circuit—blocking nerve signaling or the adrenergic signals—reawakened antitumor immunity and reduced tumor‑protective suppression. These results point to potential new therapeutic strategies that target neuroimmune communication rather than the tumor cells directly.

However, Jin, Rui Chang (Yale School of Medicine) and other authors emphasize caution: the current results are primarily in mouse models, and translating these findings into safe, effective human therapies will require extensive further research and clinical testing.

Bottom line: Lung tumors can exploit vagal sensory pathways to recruit the brain’s autonomic machinery, trigger local noradrenaline release, and reprogram macrophages to suppress T cells—creating an immune‑protected niche. Interrupting this loop restored immune activity in mice and suggests a novel angle for future cancer treatments.

Help us improve.