A study led by Peter Krawitz (University of Bonn) sequenced whole genomes from Chernobyl cleanup workers and retired Cold War–era radar operators and found a modest increase in new mutations in the children of irradiated fathers. Most additional mutations were located in non‑coding regions and were only detectable through whole‑genome sequencing. The researchers say the transgenerational effect is real but that the likelihood of these inherited mutations causing genetic disease appears low; parental age remains a larger risk factor. Larger follow‑up studies are needed to define health impacts and guide preventive measures.

Chernobyl Cleanup Linked To Mutations Detected In Children — Study Finds Modest Transgenerational Signal

A new international study led by physician‑geneticist Peter Krawitz at the University of Bonn provides genomic evidence that exposure to ionizing radiation can leave detectable traces in the next generation. The researchers sequenced whole genomes from Chernobyl cleanup workers and retired Cold War–era German radar operators and compared them with matched controls to search for inherited DNA damage.

What the Study Found

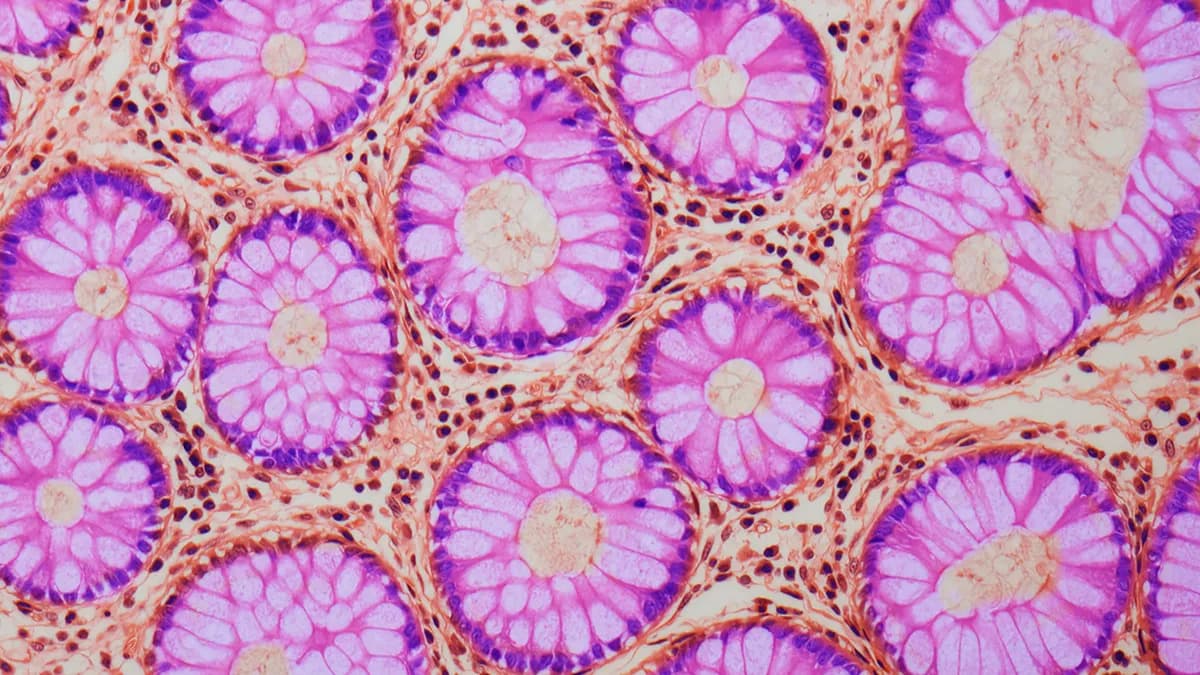

The team observed a modest but measurable increase in new (de novo) mutations in the children of fathers who had been exposed to ionizing radiation. Most of these additional mutations occurred in non‑coding regions of the genome and were only detectable through whole‑genome sequencing; they were not visible under standard cellular examination. The number of mutations correlated with paternal exposure, supporting a transgenerational effect of radiation.

How Radiation Can Affect DNA

Ionizing radiation damages cells by ionizing water molecules and producing reactive oxygen species, which can break DNA strands and oxidize DNA bases. Radiation can also cause chromosomal breaks and translocations, creating genomic instability that may manifest as mutations in sperm and, subsequently, in offspring.

Implications and Caveats

Although the study detected a transgenerational signal, the researchers emphasize that the additional mutations are mostly in non‑coding regions and that the likelihood these inherited changes will cause genetic disease appears low. Krawitz and colleagues also note that parental age at conception remains a stronger and better‑characterized risk factor for transmitting harmful variants than the modest radiation‑linked increase observed here.

"Investigation of such effects is warranted in order to design effective preventive measures," Krawitz and colleagues write in their Nature paper. "The potential of transmission of radiation‑induced genetic alterations to the next generation is of particular concern for parents exposed to higher doses or for prolonged periods."

The authors call for larger, more diverse cohort studies to better characterize the specific mutation types, quantify long‑term health consequences, and inform preventive strategies for populations exposed to ionizing radiation. For now, the study strengthens evidence that ionizing radiation can leave genomic traces in descendants while indicating that immediate public‑health risks from these inherited mutations are limited compared with other well‑established factors such as parental age.

Help us improve.