A new high-resolution model using Juno and Galileo data suggests Jupiter may hold about 1.5× the Sun’s oxygen — far above prior estimates near one-third. The result, published in The Planetary Science Journal, supports formation by accreting icy material near or beyond the solar frost line and reflects that most extra oxygen is bound as water. The model couples chemistry and hydrodynamics and finds atmospheric diffusion 35–40× slower than previously assumed, so molecules may take weeks, not hours, to cross layers.

Far More Oxygen Hidden Beneath Jupiter’s Clouds — New Model Finds 1.5× Solar Abundance

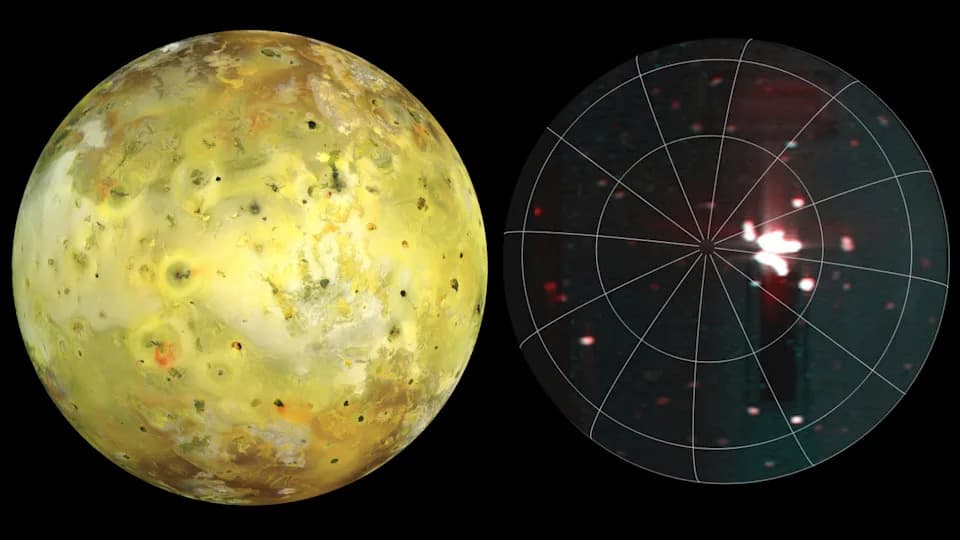

The turbulent, impenetrable cloud decks that cloak Jupiter have long kept the planet's interior a mystery. Probes that try to penetrate those layers face extreme heat and pressure: NASA's Galileo atmospheric probe, for example, lost contact almost immediately after intentionally plunging into Jupiter in 2003.

Now a team from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of Chicago has combined data from the Juno and Galileo missions to produce a high-resolution computational model of Jupiter's atmosphere. Their results, published last month in The Planetary Science Journal, reveal a surprising chemical signature: Jupiter's atmosphere may contain roughly 1.5 times the oxygen abundance of the Sun — far higher than earlier estimates that suggested about one-third of the Sun's oxygen.

Much of that extra oxygen appears to be bound up in water, and because water's behavior changes dramatically with temperature, this complicates efforts to infer Jupiter's internal layering. The new abundance supports formation scenarios in which Jupiter accreted large amounts of icy material near or beyond the solar system's "frost line" — the region far enough from the Sun for water, ammonia and methane to freeze — though whether Jupiter formed in place or migrated inward remains debated.

The model stands out because it couples detailed chemistry across a vast temperature range (from metal-bearing molecules deep inside to cooler species higher in the atmosphere) with hydrodynamic transport, including cloud and droplet microphysics. "You need both," said lead author Jeehyun Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago. "Chemistry is important but doesn’t include water droplets or cloud behavior. Hydrodynamics alone simplifies the chemistry too much. So it’s important to bring them together."

One striking implication of the simulations is that vertical transport in Jupiter's atmosphere is much slower than commonly assumed. "Our model suggests diffusion would need to be 35 to 40 times slower than standard assumptions," Yang explained. "Instead of passing through a given atmospheric layer in hours, a single molecule might take several weeks." Slower mixing affects how elements and compounds are distributed with depth and thus how we interpret remote measurements.

"It really shows how much we still have to learn about planets, even in our own solar system," Yang added.

These findings are one piece in the larger puzzle of understanding the solar system's largest planet and its diverse family of moons. Future observations by Juno and next-generation missions, combined with improved models, will be crucial to confirm the oxygen measurement and refine our picture of Jupiter's origins and internal structure.

Help us improve.