SETI@home, the distributed computing initiative launched in 1999 at UC Berkeley, will end after 27 years. Volunteers analyzed Arecibo data and produced roughly 12 billion candidate detections, most of which proved to be human-made interference. Researchers narrowed the archive to about 100 top candidates that are now being reobserved with China’s FAST telescope. SETI@home’s technical advances and large-scale public engagement are cited as its lasting legacy.

SETI@home Winds Down After 27 Years; 100 Top Signals to Be Rechecked Using China’s FAST Telescope

SETI@home, one of the longest-running public searches for extraterrestrial intelligence, will conclude this year after 27 years of volunteer-driven analysis. Launched in 1999 at the University of California, Berkeley, the distributed-computing project asked millions of people to donate spare processor cycles from their home computers to sift radio data gathered by the Arecibo Observatory.

Final Follow-Up: The Strongest Candidates

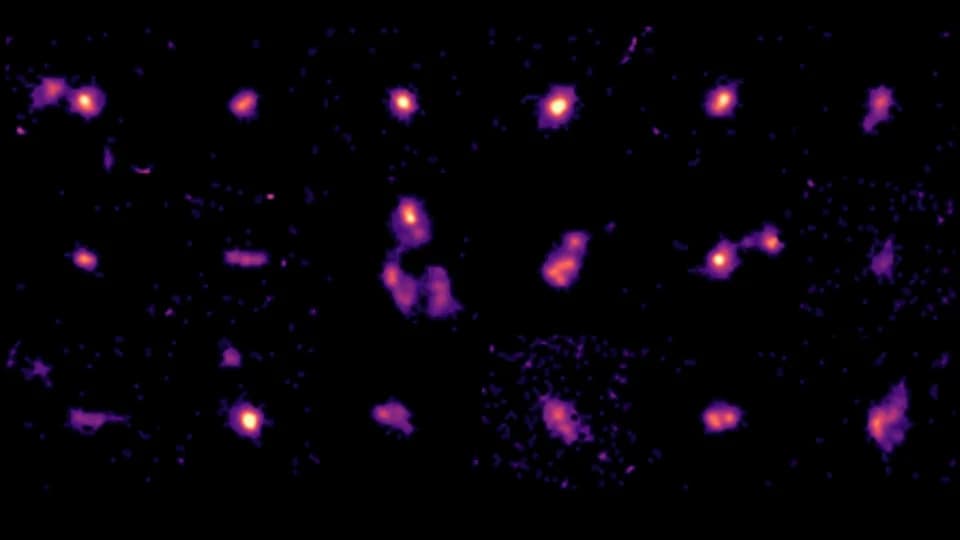

Researchers have winnowed roughly 12 billion candidate detections from 14 years of Arecibo observations down to about 1 million and now to a final set of roughly 100 top candidates. Those candidates are being rechecked with the Five Hundred-Meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) in China in the hope of re-detecting persistent emissions from the same sky locations and frequencies. Once that follow-up is complete, the SETI@home effort will be formally wound down.

How the Project Worked

At its peak the project enlisted more than 5 million volunteers, who installed free software that analyzed raw Arecibo data for brief energy spikes that might indicate an artificial signal. SETI@home was a pioneering example of distributed computing in an era before widely available high-speed internet and modern cloud computing.

- Data Archive: Volunteers processed data collected over about 14 years, covering nearly the entire sky visible to Arecibo while it performed other observations.

- Candidate Volume: The analysis produced roughly 12 billion candidate detections, the vast majority of which were later identified as radio-frequency interference from satellites, terrestrial transmitters and other human-made sources.

- Blind Tests: To calibrate detection software, researchers injected artificial test signals called "birdies" into the data stream to measure sensitivity and validate algorithms.

Legacy and Lessons

Project co-founders and collaborators highlight several enduring accomplishments: the demonstration of large-scale citizen science, advances in signal-detection sensitivity beyond conventional spectroscopic methods, and a robust distributed-computing platform that can be repurposed for other scientific problems such as cosmology, pulsar research and even biomedical computation.

"We had to automate much of the cleanup, but in the end we manually inspected candidates to discard obvious interference," said David Anderson of UC Berkeley's Space Sciences Laboratory, summarizing the decade-long effort to refine billions of detections into the final candidates.

Co-founder Eric Korpela said the project also proved that public engagement could complement mainstream astronomy rather than hinder it, sparking broad interest in the search for life beyond Earth. Other leaders in the field — including Breakthrough Listen collaborators at NSF, NRAO and the Green Bank Observatory, and researchers at METI International — praised SETI@home for its technical innovations and for inspiring a new generation of researchers.

Arecibo: From Repair to Collapse

The Arecibo Observatory, which provided the raw data SETI@home analyzed, was damaged by Hurricane Maria in 2017 and returned to service, but it ultimately collapsed in 2020 after long-term structural degradation of the filled spelter sockets that anchored its support cables. The Arecibo dataset nevertheless remains a rich scientific resource.

What Comes Next

With the FAST follow-up under way and two methodology papers published recently describing lessons learned, SETI@home's infrastructure and human-network model remain valuable. Researchers say the project's tools and public-engagement lessons will inform future searches for techno-signatures and other collaborative scientific efforts.

Help us improve.