The saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) has not been widely documented since a 2013 camera-trap photo, leaving a 13-year gap as of January 2026. Only about 30% of its potential Annamite Mountains range has seen any survey and just 2–5% has been intensively searched for saola. Conservationists now pair local interviews and camera traps with modern tools—dung/eDNA sampling and leech blood analysis—to detect the species without visual proof. The IUCN SSC calls for targeted, cross-border searches, improved detection technology and rapid-response plans to protect any survivors.

The Saola: Inside the Search for Asia’s Most Elusive Large Mammal

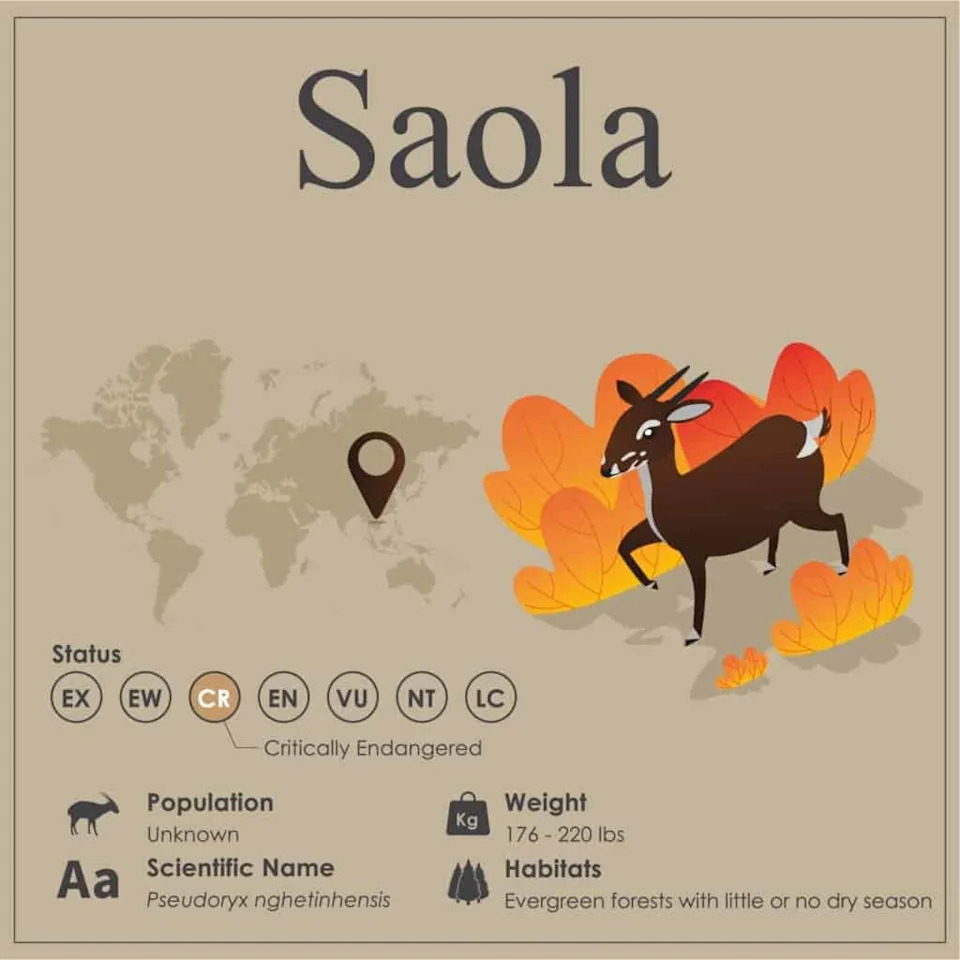

The saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) remains one of the world’s most mysterious large mammals. First documented in 1992 and restricted to the Annamite Mountains along the Vietnam–Laos border, it has not been widely documented since a 2013 camera-trap image. That 13-year gap (as of January 2026) complicates efforts to confirm whether any viable populations persist and to mount timely protections if they do.

Why the Saola Is So Hard to Find

The saola favors steep, wet, dense, largely roadless forest where only a few narrow trails penetrate vast tracts of potential habitat. These conditions challenge people and equipment alike: camera traps must be precisely sited to catch animals moving along narrow micro-routes, and even long-term deployments can return no images when animals are extremely scarce.

How Much Habitat Has Been Surveyed?

Survey effort is limited. Roughly 30% of the saola’s potential range has seen any wildlife survey at all, and only an estimated 2–5% of that area has been intensively searched specifically for saola. Large portions of its habitat remain remote and under-surveyed, increasing the chance that small, isolated populations could persist undetected.

Detecting an Animal Without Seeing It

Because visual confirmation is rare, researchers rely on indirect but verifiable methods: structured interviews with local people to build sighting histories; environmental DNA (eDNA) from dung and water samples; and genetic analysis of blood meals from leeches. These approaches can produce location-linked evidence—even a single verified DNA sample from a watershed or an insect could be decisive.

Threats

Even if saola remain, they face immediate, escalating threats. Wire snares set for more common wildlife are indiscriminate and can capture any medium-to-large mammal that moves through the understory. Habitat loss from agriculture and infrastructure, increased human access, and ongoing hunting pressure compound the risk. Climate change and tourism are additional concerns, though not currently judged the leading threats.

What Conservationists Are Doing

The IUCN Species Survival Commission urges a stepped-up, coordinated response: targeted searches in the most plausible remaining habitat, improved cross-border collaboration between Vietnam and Laos, technological innovation in detection methods, and a readiness plan so that immediate protective actions (snare removal, anti-poaching presence, and habitat safeguards) can follow any credible lead.

What Would Count as a Rediscovery?

Rediscovery could take multiple forms: a clear camera-trap photo in the right location, a verified DNA sample tied to a specific watershed or collected from an insect or dung, or a credible cluster of recent local reports that point to a single area. Because the window to act may be short after confirmation, speed and coordination will determine whether rediscovery leads to sustained protection.

Bottom line: The saola is a real but extraordinarily elusive species. Absence of recent photos does not prove extinction, but the combination of its low detectability and growing threats makes urgent, well-coordinated detection and rapid protection essential.

Help us improve.