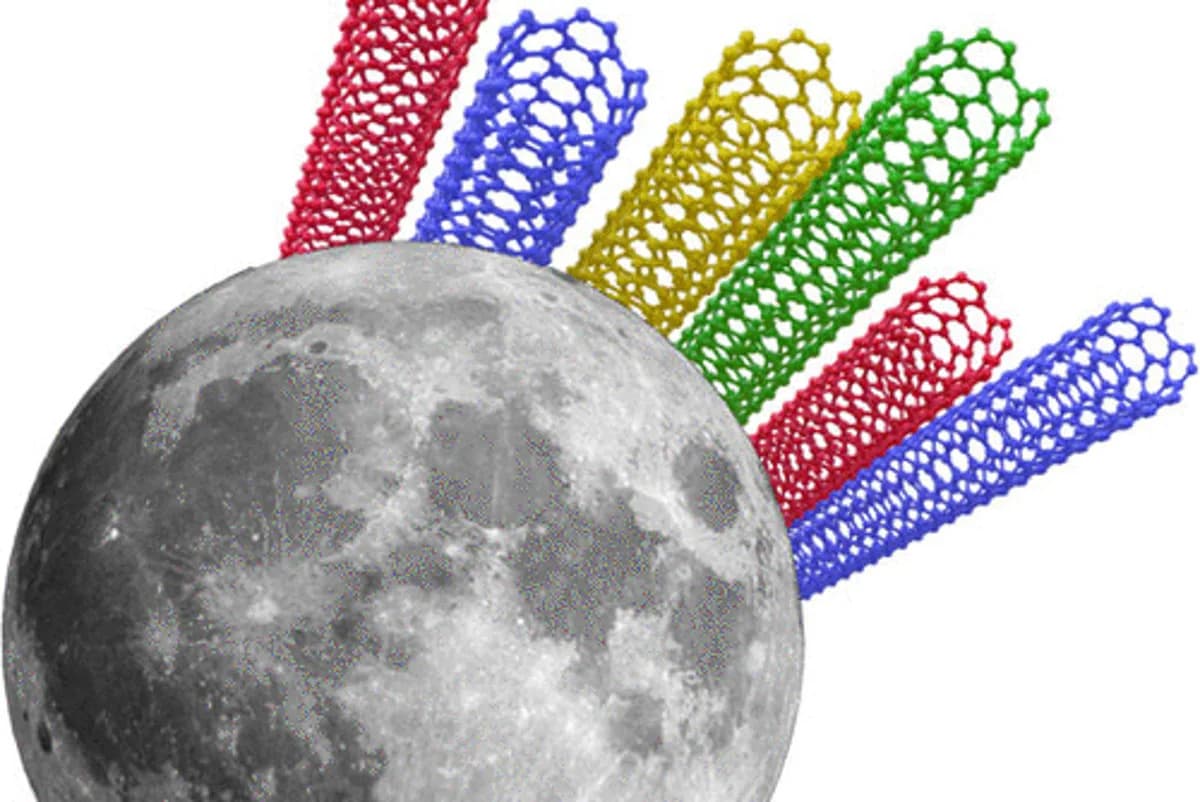

Researchers have recreated an Edison-style bulb test and shown that carbon filaments like the Japanese bamboo Edison used can yield graphene when flash-heated briefly. Graduate student Lucas Eddy connected an authentic bamboo filament bulb to 110V DC for about 20 seconds and detected graphene-like signals by laser-based spectroscopy. The work, published in ACS Nano, suggests historic incandescent experiments may have briefly produced advanced materials long before they were understood.

Did Edison’s Early Light Bulbs Accidentally Produce Graphene? Scientists Recreate Bamboo-Filament Test

When Thomas Edison perfected his practical incandescent lamp in 1879, he experimented with carbonized plant filaments—most famously Japanese bamboo—that allowed bulbs to glow for exceptionally long periods. Modern researchers have now shown that filaments like those Edison used can produce graphene when briefly flash-heated, suggesting historic experiments may have briefly yielded advanced materials long before their discovery.

Edison’s Filament Experiments

Edison originally aimed to use tungsten for filaments but manufacturing constraints led him to carbonized plant fibers: organic materials heated without air that leave a carbon-rich residue. He tested thousands of materials—later recalling he tried “no fewer than 6,000 vegetable growths”—and found Japanese bamboo filaments that reportedly lasted more than 1,200 hours in some trials.

“Before I got through, I tested no fewer than 6,000 vegetable growths, and ransacked the world for the most suitable filament material.”

Recreating the Effect in the Lab

Lucas Eddy, a nanomaterials researcher then at Rice University, wondered whether such carbon filaments could yield graphene if rapidly heated. One method known to produce graphene is flash Joule heating—very fast heating of carbon-rich materials above roughly 3,600°F (about 1,980°C). Eddy searched for authentic carbon-filament bulbs (many collectors’ bulbs actually used tungsten) and eventually found examples with Japanese bamboo filaments at a small New York art shop.

Following an Edison-style setup, Eddy connected a bulb to a 110-volt direct-current source and ran current for about 20 seconds; longer heating tends to favor the formation of graphite, a thicker carbon allotrope. Using laser-based spectroscopy to analyze the treated filament, he and colleagues reported signatures consistent with graphene in a paper published in ACS Nano.

What This Means

It’s unclear whether Edison himself ever produced graphene: his famous 1879 demonstration bulb reportedly burned for more than 13 hours—ample time for any nascent graphene to convert to graphite. Scientists didn’t even propose graphene’s theoretical existence until 1947, and atom-thin graphene layers were first isolated only in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, work that earned them the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics.

“To reproduce what Thomas Edison did, with the tools and knowledge we have now, is very exciting,” said co-author James Tour of Rice University. “What questions would our scientific forefathers ask if they could join us in the lab today? What questions can we answer when we revisit their work through a modern lens?”

Whether or not Edison recognized such microscopic outcomes, this modern replication highlights how revisiting historical experiments with contemporary tools can uncover overlooked phenomena and inspire new research directions.

This story originally appeared in Nautilus and was reported in the journal ACS Nano.

Help us improve.