The Hora 1 shelter at Mount Hora in northern Malawi contains the oldest confirmed cremation in Africa: a woman cremated about 9,500 years ago. Micromorphology and bone analysis show the pyre reached temperatures above 932°F (500°C), used roughly 70 lb (30 kg) of dry wood, and was actively stoked, producing an ash mound the size of a queen bed. Cut marks and missing skull fragments indicate deliberate dismemberment and possible secondary ritual treatment, while flaked stone points suggest funerary offerings. The discovery reveals unexpected complexity in hunter‑gatherer mortuary practices and the long‑term ritual significance of the site.

9,500-Year-Old Cremation at Mount Hora Reveals Complex Hunter‑Gatherer Rituals

Burned human bone fragments recovered beneath a boulder overhang at the Hora 1 shelter, near Mount Hora in northern Malawi, identify the oldest confirmed cremation pyre in Africa. Radiocarbon dating and sediment analysis indicate hunter‑gatherers intentionally cremated a woman about 9,500 years ago, a practice that appears to have been exceptional at this site.

Discovery and Archaeological Context

Hora 1 sits beneath a large granite overhang that could shelter roughly 30 people. Excavations beginning in the 1950s identified the location as a hunter‑gatherer burial ground; renewed work from 2016 to 2019 by the Malawi Ancient Lifeways and Peoples Project revealed human occupation at the site as far back as ~21,000 years ago, with burials dating between about 8,000 and 16,000 years ago.

Evidence for a Deliberate Cremation

Archaeologists uncovered an ash mound roughly the size of a queen bed that contained two concentrated clusters of calcined human bone. Micromorphological analysis of the pyre sediments shows temperatures exceeded 932°F (500°C). The burning patterns, the size of the ash deposit, and wood‑char remains indicate the blaze likely burned for several hours to days and was actively refueled.

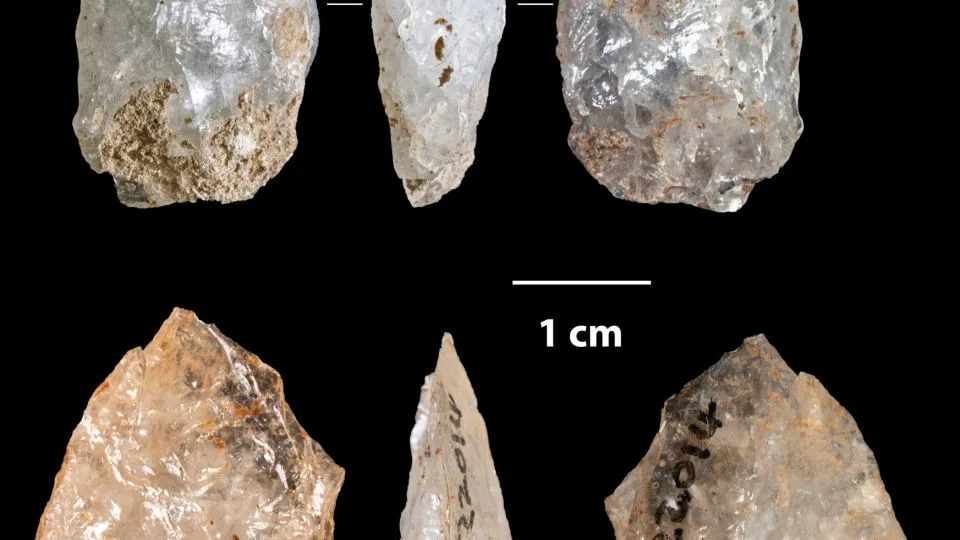

Analysis of the fuel shows fungus and termite damage on the wood, implying that about 70 pounds (≈30 kg) of dry deadwood were gathered — a considerable investment of time and labor. Flaked stone points found on the pyre appear to have been placed as funerary objects.

Human Remains and Treatment of the Body

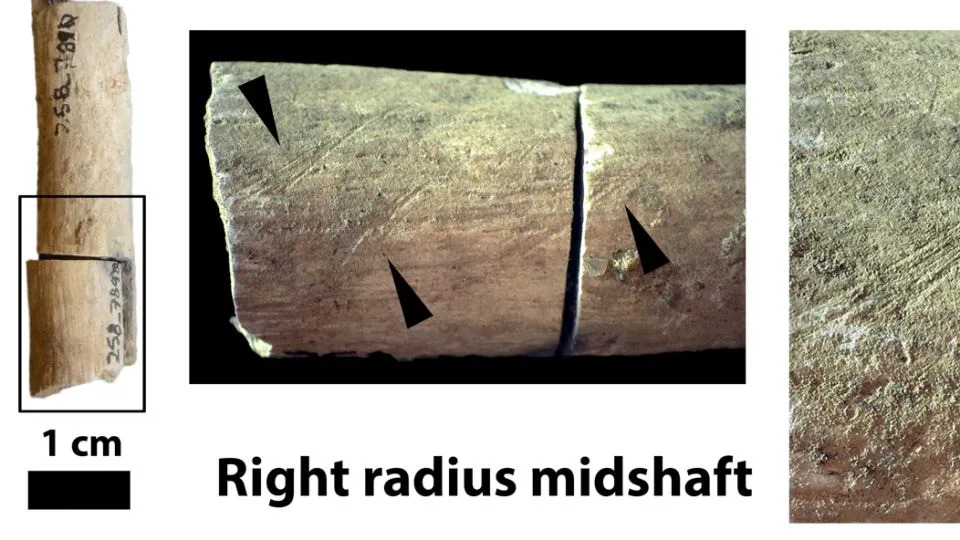

Forensic analysis attributes the fragments—mostly arm and leg bones—to a single adult woman, likely between 18 and 60 years old and just under 5 feet tall. Cut marks on the bones indicate people removed flesh before burning, apparently to aid cremation. The researchers ruled out cannibalism because cut‑mark patterns differ from those found on animal bones from the site.

Notably, there were no skull or tooth fragments in the pyre—elements that typically survive cremation—leading the team to conclude the head may have been removed prior to burning, possibly for posthumous curation or secondary ritual use.

"Cremation is very rare among ancient and modern hunter‑gatherers, at least partially because pyres require a huge amount of labor, time, and fuel," said Jessica Cerezo‑Román (University of Oklahoma), lead author of the study published in Science Advances.

Why This Case Matters

The Hora 1 cremation predates previously documented cremations in Africa, which are generally linked to pastoralist or agricultural societies thousands of years later. The find demonstrates that highly organized, labor‑intensive mortuary practices existed among some hunter‑gatherer groups nearly 10,000 years ago and points to sophisticated belief systems and social coordination.

Additional evidence indicates the location retained ritual significance over centuries: large fires were lit in the same spot about 700 years before the cremation and again roughly 500 years afterward, suggesting Mount Hora functioned as a long‑lasting landmark for remembrance or communal ritual.

Open Questions and Ongoing Research

Why this woman received cremation while others at Hora 1 were given inhumations remains unclear. Her bones suggest lower mobility and unusually heavy arm use compared with other individuals at the site, but whether her treatment represents honor, punishment, or another social circumstance is unknown. Researchers recommend studying similar rock‑shelter sites and revisiting museum collections to better understand the diversity of ancient African mortuary practices.

Study and Team: The research was published in Science Advances and led by Jessica Cerezo‑Román, with coauthors including Jessica Thompson (Yale University) and Elizabeth Sawchuk (Cleveland Museum of Natural History), as part of the Malawi Ancient Lifeways and Peoples Project.

Help us improve.