The Monroe Doctrine began as three paragraphs in James Monroe's 1823 address and was not a law but a presidential warning to European powers. Over time presidents such as James K. Polk and Theodore Roosevelt repurposed it to justify territorial expansion and preemptive interventions in Latin America, culminating in the early 20th-century "Banana Wars." Though it faded after World War II, the doctrine has reappeared in recent political rhetoric, most recently invoked in discussions about Venezuela.

How Three Paragraphs Became U.S. Policy: The Surprising History Of The Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine — a brief passage in President James Monroe's 1823 address to Congress — has had an outsized and evolving influence on U.S. policy in the Western Hemisphere. What began as a short warning to European powers has been repeatedly reinterpreted and invoked by later presidents to justify expansion, intervention, and a hemispheric sphere of influence.

How It Began

Historian Jay Sexton, author of a book on the Monroe Doctrine, notes that the original language comprised only a few paragraphs and was aimed squarely at Europe:

"The American continents... are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers."Monroe's statement was a presidential policy declaration, not a law or binding treaty.

From Statement To Doctrine

It took decades for Monroe's brief message to be treated as a guiding doctrine. In 1846 President James K. Polk cited the principle in the context of the war with Mexico — a conflict that contributed to a near doubling of U.S. territory.

The Roosevelt Turn And The Corollary

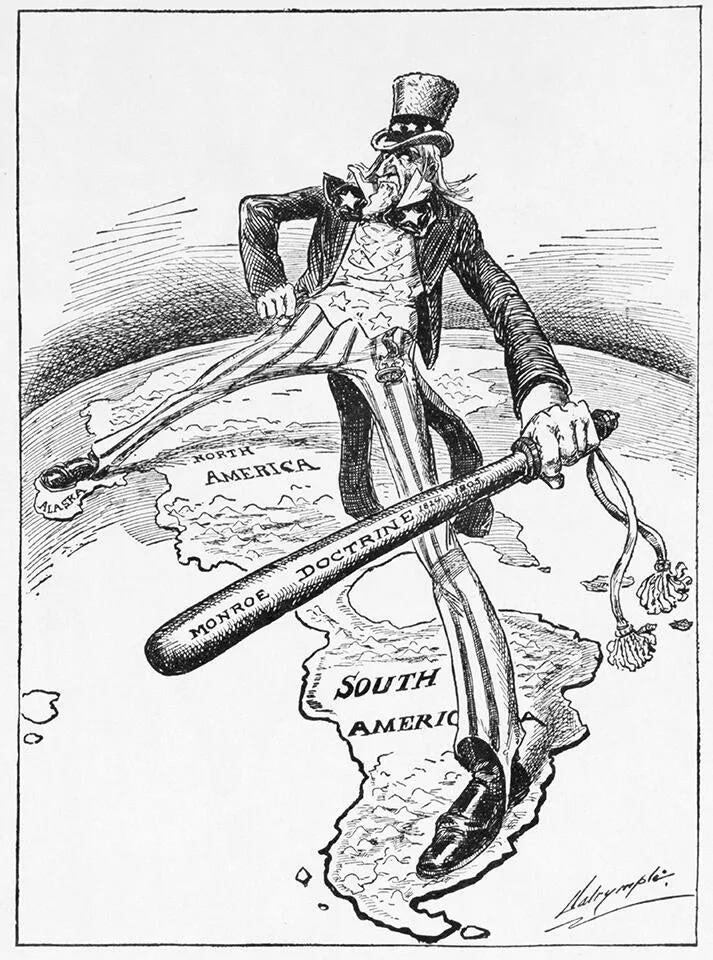

By 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt gave the Monroe Doctrine new teeth with his corollary: worried that European powers might exploit instability in the Caribbean and Central America, Roosevelt argued the United States should act preemptively to keep external powers out. As historian Sexton summarizes, Roosevelt effectively told regional governments: maintain order or the United States will intervene for you.

"Big Stick" Interventions And The Banana Wars

That logic helped justify repeated military interventions. By the 1920s U.S. Marines were present in roughly half a dozen countries across Latin America and the Caribbean, protecting American business interests — from banana plantations to banking operations. These occupations, known collectively as the "Banana Wars," produced hundreds of military casualties and many thousands of civilian deaths, and became deeply unpopular at home and abroad.

Decline And Resurgence

After World War II the Monroe Doctrine receded from everyday political discourse. During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy reportedly dismissed it as less relevant to the Cold War contest: "The Monroe Doctrine, what the hell is that?"

Decades later, the doctrine reappeared in modern political rhetoric. In discussions about recent events in Venezuela, President Donald Trump publicly invoked the Monroe Doctrine, saying it had been forgotten but would no longer be ignored.

Why This Matters

The Monroe Doctrine's history shows how a short presidential statement can be adapted over time to justify a wide range of policies — territorial expansion, military intervention, and economic protectionism — often with profound human and geopolitical consequences.

Further reading: Jay Sexton, The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America (Hill and Wang). Sexton is a professor of history at the University of Missouri.

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Chad Cardin.

Help us improve.