Archaeologists working at a Pompeii site buried by Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 uncovered direct evidence that Roman builders used a "hot‑mixing" method for concrete: dry lime fragments and volcanic ash were combined before water was added, producing heat and trapping lime clasts that later enable self‑healing. The findings, published December 9 in Nature Communications, corroborate earlier results from Privernum and challenge the sequence described by Vitruvius in De architectura. Scholars say the discovery highlights the practical expertise of everyday builders and could inform modern, more durable construction techniques.

Pompeii Time Capsule Reveals Roman 'Hot‑Mix' Concrete Recipe — Challenges Vitruvius

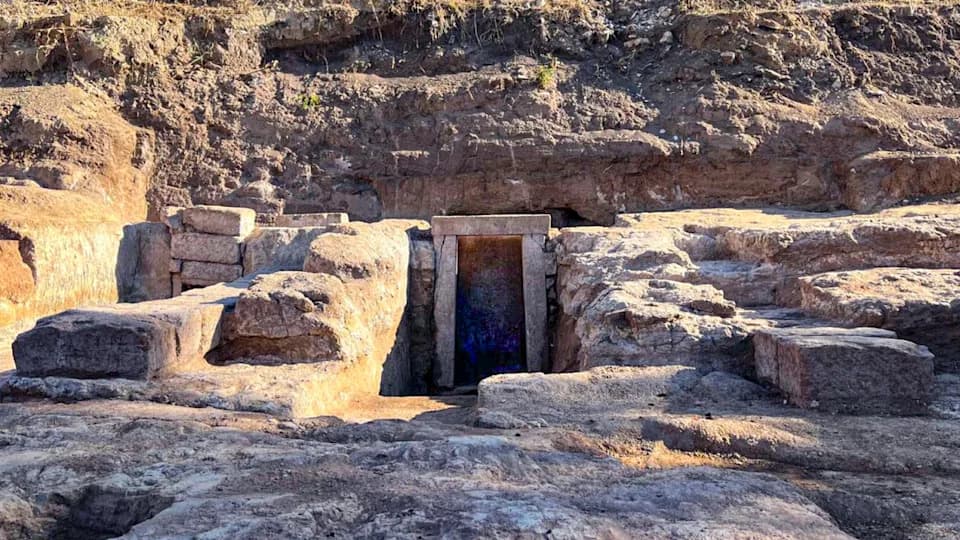

The excavation of a Pompeii construction site frozen by Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 has yielded the clearest physical evidence yet for how Romans made their extraordinarily durable, self‑healing concrete. International researchers who reopened the site in 2023 found finished walls, partially built sections, piles of pre-mixed dry materials and tools that document an active building operation halted by the eruption.

Lead researcher Admir Masic, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT and lead author of the new study, described the site as "a time capsule." He said the preservation allowed his team to reconstruct the builders' methods with unusual clarity.

What the Team Found

Analyses published December 9 in the journal Nature Communications show evidence that Roman builders used a hot‑mixing technique: lime fragments (lime clasts) were combined with dry volcanic ash and other dry ingredients first, and water was added afterward. The chemical reaction that follows is exothermic — it generates heat — which helps trap lime clasts within the concrete matrix.

Those trapped lime clasts are key to the material’s longevity: when cracks form and moisture reaches the clasts, the lime can dissolve, migrate into fractures and recrystallize as it dries, effectively sealing and “self‑healing” the concrete.

How This Challenges Vitruvius

The sequence observed at Pompeii differs from the procedure described in the first‑century treatise De architectura by Vitruvius, who wrote that water should be mixed with lime before other ingredients. The Pompeii evidence—complementing Masic’s earlier 2023 analysis of a Privernum wall—supports hot‑mixing as a practical workshop method used by builders rather than Vitruvius’ prescribed order of operations.

"It’s really difficult to think that Vitruvius was wrong. And I respect Vitruvius..." — Admir Masic

John Senseney, an associate professor of ancient history at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the study, noted that elite written prescriptions often do not reflect everyday practice. He emphasized that this discovery highlights the skill and innovation of ordinary craftsmen and enslaved laborers whose practical expertise built monuments like the Pantheon and the Colosseum.

Why It Matters

Beyond rewriting aspects of construction history, the findings may have practical implications for modern materials science. Understanding how ancient hot‑mixing trapped reactive lime fragments and created long‑lasting, self‑repairing concrete could inspire more durable and sustainable contemporary construction techniques.

About one‑third of Pompeii remains unexcavated, leaving open the prospect of more discoveries that could further illuminate Roman building technology. For now, the 2023 excavation offers a rare, visceral glimpse of workers mid‑construction and provides a tangible link between ancient practice and modern scientific study.

Publication Note: The study was published in Nature Communications (December 9). The Pompeii site was first investigated in the late 1880s and reopened for excavation in 2023, when researchers documented the preserved building activity.

Help us improve.