Researchers model how thinning ice shells on small outer‑solar‑system moons can reduce pressure enough for subsurface oceans to reach water's triple point, causing low‑temperature boiling near the ice. This effect is predicted for the tiniest moons (e.g., Enceladus, Mimas, Miranda) when shells thin by about 3–9 miles (5–15 km). Boiling would occur near 0°C and likely would not sterilize deeper ocean layers, while larger moons tend to fracture before boiling begins. The study appears in Nature Astronomy.

Small Icy Moons Could Host Low‑Temperature Boiling Oceans — Life Might Still Survive

New modeling suggests that some of the smallest icy moons in the outer solar system may hide subsurface oceans that begin to boil when their ice shells thin — yet conditions deeper in those oceans could remain habitable.

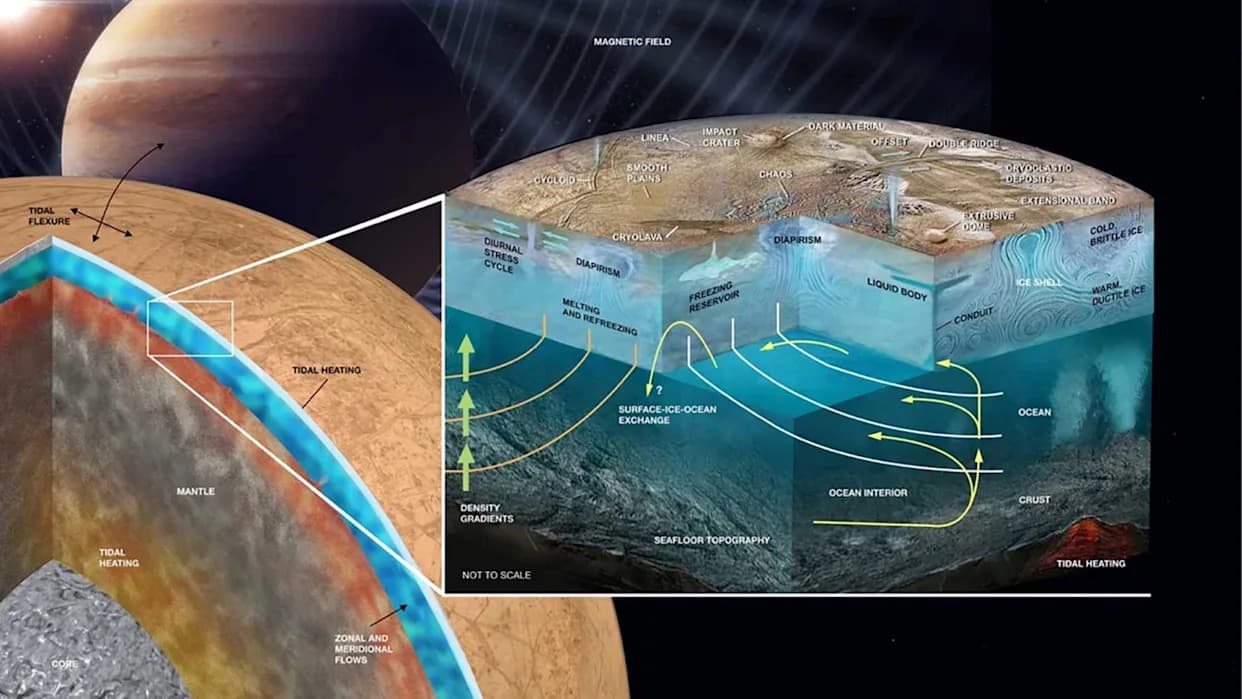

Geophysicist Maxwell Rudolph of the University of California, Davis, and his colleagues modeled how stresses and pressures change when an ice shell changes thickness over hundreds of millions of years. Earlier studies showed that certain moons, such as Saturn's Enceladus, contain liquid layers between an outer ice shell and a rocky core. Because liquid water is central to life on Earth, these concealed oceans are priority targets in the search for potential extraterrestrial habitability.

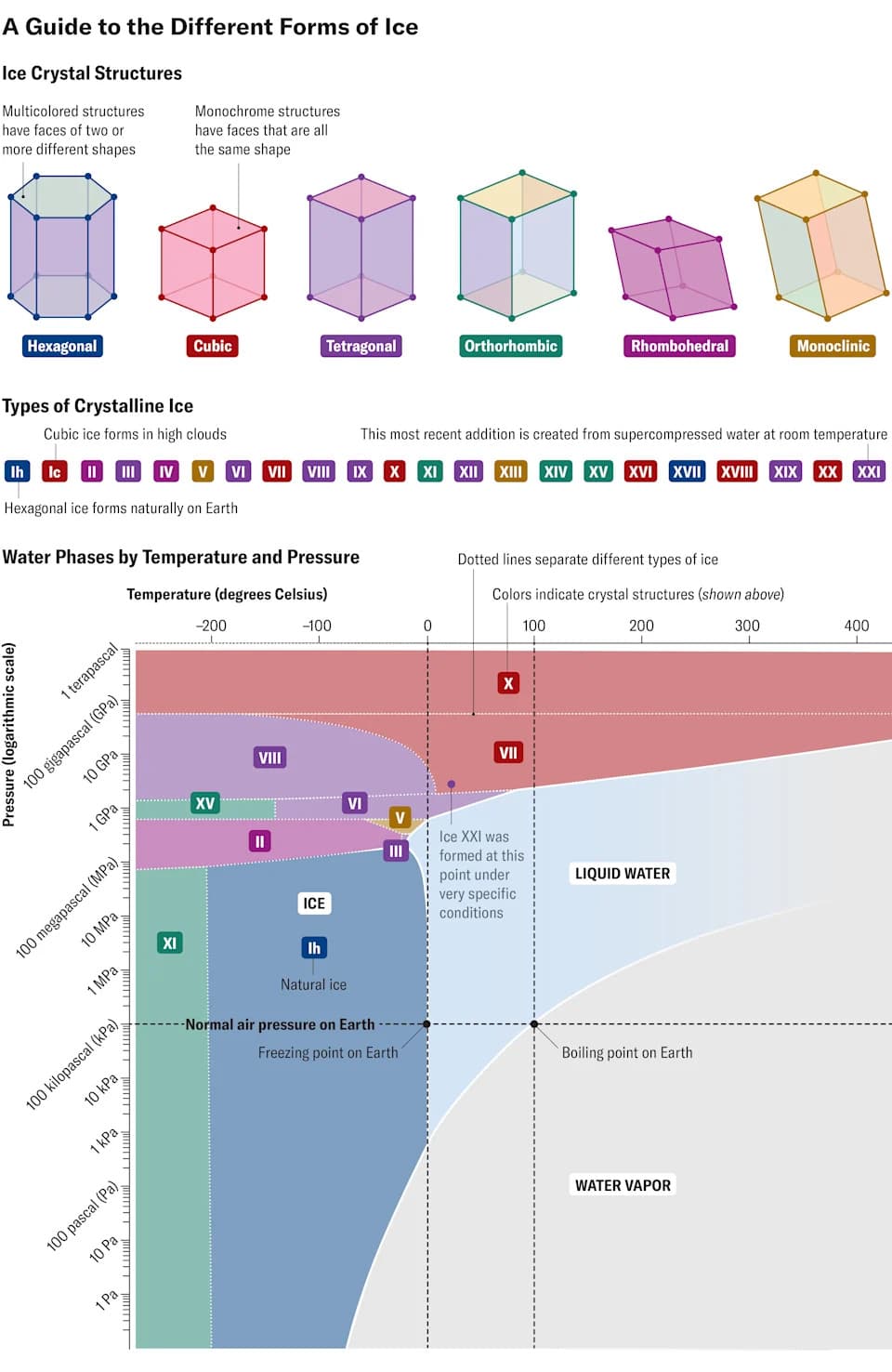

The team focused on what happens when an icy shell thins from below — for example, through basal melting driven by tidal heating or orbital interactions. Their models indicate that as the shell thins, pressure on the underlying ocean drops. On very small moons (examples include Enceladus, Mimas and Uranus's Miranda), that pressure decline can reach water's triple point — the temperature and pressure where ice, liquid water and vapor can coexist. If a shell thins by roughly 3–9 miles (5–15 kilometers), the upper layers of the ocean nearest the ice could begin to boil.

Rudolph emphasizes this is low‑temperature boiling, not the high‑temperature bubbling familiar from kitchen stoves. "It's boiling very close to 0°C [32°F]," he said. "So for any potential life forms below that boiling area, life could go on as usual." The boiling is driven by a pressure drop rather than by heating the water to high temperatures.

By contrast, on larger moons with radii above about 370 miles (600 kilometers) — for example Uranus's Titania — the models show the ice shell is more likely to fracture before pressures fall enough to reach the triple point. The authors suggest some of Titania's surface structures, such as wrinkle ridges, could reflect a history of ice‑shell thinning followed by re‑thickening and stress relief.

The emergence of vapor from a boiling layer could also release gases that form clathrates (solid, cage‑like ices that trap gas molecules) or generate distinctive surface features. The researchers say future work should trace what happens to gases released from these oceans and predict what surface signatures — cracks, deposits or clathrate formations — would accompany such processes.

The study, led by Maxwell Rudolph, was published online Nov. 24 in the journal Nature Astronomy. Observations cited in the work include evidence that Mimas may have developed a subsurface ocean within the last ~10 million years, inferred from its orbital wobble combined with a heavily cratered surface that indicates limited recent resurfacing.

Why this matters

These findings broaden our view of where liquid water — and possibly habitable environments — can exist in the solar system. Boiling at low pressure could alter ocean chemistry and the exchange of materials between ocean and surface, but it does not necessarily make the entire ocean sterile. Understanding these dynamics will help prioritize targets for future missions searching for signs of life.

Help us improve.