What they do: Particle accelerators boost charged particles and make them collide so their constituents can be revealed. How they work: Timed electric fields add energy while superconducting magnets steer and focus beams. Example: The LHC uses a 27 km ring, RF cavities, and magnets chilled to about −271°C to bring protons to ~99.999% of light speed before colliding them. Why it matters: Collisions confirm predicted particles like the Higgs and expose gaps in our theories, driving new questions and discoveries.

Inside Particle Accelerators: How Scientists Smash Particles to Reveal Nature's Secrets

Every time two particle beams cross inside an accelerator, researchers get a brief, controlled glimpse of nature at its smallest scales. Collisions can reveal previously unseen particles or recreate conditions like those that existed in the first instants after the Big Bang. Particle accelerators don't aim for speed for its own sake — they produce collisions energetic enough to force subatomic structure into view.

How accelerators do it

Two physical tools make acceleration and control possible. Electric fields supply energy by giving particles precisely timed, incremental pushes. Magnetic fields steer and focus the beams so the charged particles stay on course and can be concentrated into tight packets that will collide.

Straight lines or giant rings

Some accelerators send particles down straight tunnels; others use immense circular rings where beams circulate thousands of times, gaining a little energy on each lap. By the time they meet, collisions can briefly reproduce the extreme conditions of the early universe. This approach helped establish the reality of quarks and — decades after it was predicted — uncovered the Higgs boson.

The Large Hadron Collider: a practical example

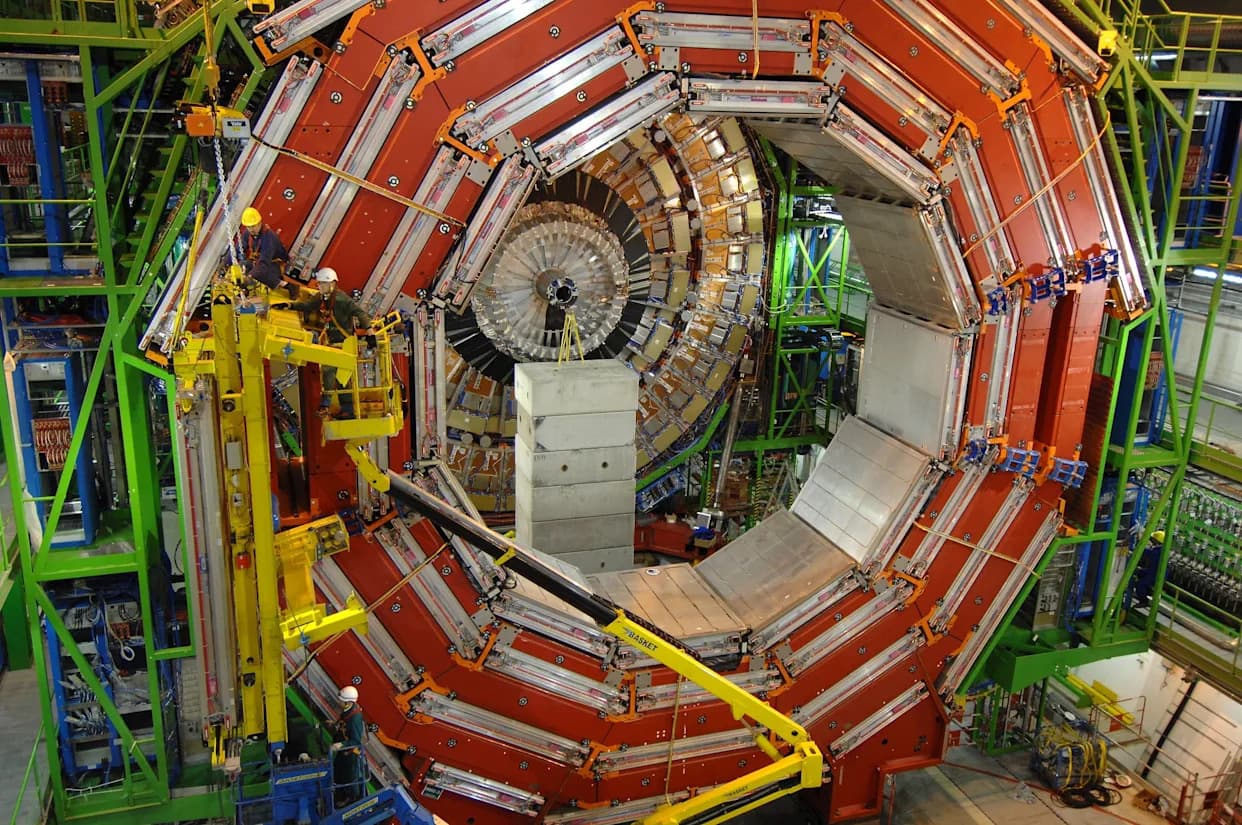

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is the best-known example of a modern, high-energy collider. It runs in a 27-kilometre (about 17-mile) underground ring where protons travel in tightly packed bunches through an ultra-high vacuum — in many respects cleaner than much of interplanetary space. Along the ring, radio-frequency (RF) cavities act like engine pistons: each cavity gives a tiny, precisely timed kick so protons gain energy a bit at a time until they approach the speed of light.

Acceleration must be paired with control. Hundreds or thousands of superconducting magnets line the tunnel and are kept near a few degrees above absolute zero (about −271°C) in liquid helium so they produce the intense magnetic fields needed to bend and focus the beams. Two beams travel in opposite directions and reach speeds so high — roughly 99.999% of light speed — that collisions occur with enormous effective energies.

Detectors and discoveries

At a handful of interaction points around the ring, the beams cross and massive detectors — multi-layered arrays of sensors and electronics — watch the debris from collisions. Most events are routine, but occasionally a rare signature appears. In 2012, such a signal led to the discovery of the Higgs boson, the particle associated with the mechanism that gives many elementary particles mass.

Why collisions matter

The goal of these experiments is not cinematic explosions but the quiet instant after a collision, when fragments and energy traces briefly expose internal structure. Physicists sift these traces for patterns that confirm theoretical predictions or point to inconsistencies. Each precise measurement either tightens our theories or reveals new puzzles that push the science forward.

Beyond particle hunting, accelerators are rigorous tests of our understanding of the universe. They reproduce extreme conditions, validate and refine theoretical models, and keep fundamental questions alive — reminding us that, even with landmark discoveries like the Higgs, much remains to be learned.

Help us improve.