Physicists have long considered whether extra spatial dimensions could explain why gravity is far weaker than the other forces. If gravity spreads into compactified dimensions, it would appear diluted in our four-dimensional world and produce a tower of massive graviton states. Collider experiments and precision short-range gravity tests have found no definitive signals so far, but warped extra-dimension models (Randall–Sundrum) can hide those signatures while still addressing the hierarchy problem. The idea remains speculative but continues to drive theoretical and experimental work.

Could Extra Dimensions Be Hiding in Plain Sight—and Explain Gravity's Weakness?

In 1919 physicist Theodor Kaluza proposed that additional spatial dimensions might help resolve deep puzzles in physics. Although we have not detected anything beyond the familiar four-dimensional fabric of space and time, the idea of extra dimensions remains an intriguing possibility that could reshape how we understand gravity.

The hierarchy problem: One of the central mysteries is why gravity is so weak compared with the other fundamental forces. Gravity's observed strength is billions of times smaller than electromagnetism or the nuclear forces, and physicists call this the “hierarchy problem.”

One elegant proposal is that gravity is not intrinsically weak but appears weak because it can spread into additional spatial dimensions that the other forces cannot access. In that picture, the electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions are confined to our four-dimensional slice of the universe, while gravity leaks into extra compact dimensions. That leakage dilutes gravity’s apparent strength in everyday life.

To avoid obvious contradictions with everyday experience, these extra dimensions must be compactified — curled up at very small scales so we do not perceive extra directions of motion. In some models the compactification scale can be surprisingly large by particle-physics standards. For example, the ADD proposal (Arkani-Hamed, Dimopoulos and Dvali, 1998) showed that with several extra dimensions the compactification radius could approach sub-millimeter scales (~0.1 mm), large enough to have produced experimental signatures if other forces accessed them.

How hidden dimensions would show up: Quantum mechanics and the wave nature of particles imply that motion in a compactified dimension appears in four dimensions as a sequence of heavier states — a Kaluza-Klein tower. A particle that is massless in higher dimensions (like a graviton) would appear in our 4D world as a set of massive excitations. Those massive modes could be seen as resonances in high-energy collisions or as deviations from Newton’s law at short distances.

Physicists have therefore pursued two complementary experimental routes: high-energy collider searches for massive graviton-like particles and precision tabletop tests of gravity at sub-millimeter distances. So far, neither approach has produced evidence of extra dimensions. Collider experiments, including the Large Hadron Collider, have not observed the predicted resonances, and sensitive torsion-balance experiments have found no deviation from Newtonian gravity down to tens of micrometers in many setups. These null results force the simplest large-extra-dimension scenarios into increasingly constrained parameter ranges.

Warped extra dimensions: A key refinement came in 1999 when Lisa Randall and Raman Sundrum proposed models with a single extra dimension that is highly curved or “warped.” The Randall–Sundrum framework can naturally generate large apparent differences in scale while suppressing the couplings of massive graviton modes to ordinary matter. In other words, warped geometries can both address the hierarchy problem and hide experimental signatures from current detectors.

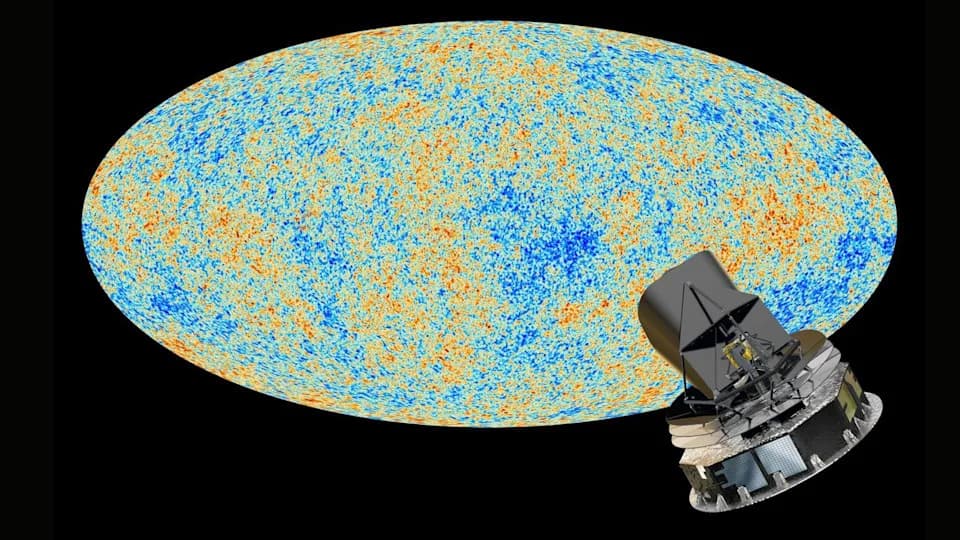

That combination—elegant theory but challenging detection—explains why extra dimensions remain theoretically attractive despite the lack of evidence. Researchers continue to push experimental limits and develop new observables, from improved short-range gravity tests to refined collider analyses and cosmological probes.

Bottom line: Extra dimensions are still a plausible and creative way to think about gravity’s weakness, but current experiments have not found them. They remain a speculative but productive idea that guides both theoretical work and experimental searches for physics beyond the Standard Model.

Help us improve.