Researchers led by Joshua Cuddihy (Imperial College London) searched for signs that long‑term exposure to burns influenced human genetic evolution. By comparing transcriptomes from burned and unburned skin in humans and rats, they identified a subset of burn‑responsive genes that show accelerated evolution. Those genes primarily control wound closure, inflammation and immune responses, but they also activate after other tissue damage, so fire is not the only possible selective pressure. The team suggests the approach could improve burn research and explain limits in translating animal models to humans.

Did Fire Shape the Human Genome? Evidence From Burn‑Response Genes

Our control of fire is often cited as one of the defining achievements of humanity: we cook food, harden tools, stay warm, and deter predators with it. Given how central fire has been to human life for hundreds of thousands of years, researchers have asked whether chronic exposure to burns left a detectable imprint on our DNA.

A multidisciplinary team led by Joshua Cuddihy at Imperial College London recently investigated that question by searching for signs of positive selection in genes activated after burn injury. Their results, published in BioEssays, identify a subset of burn‑responsive genes that show hallmarks of accelerated evolution.

How the Study Was Done

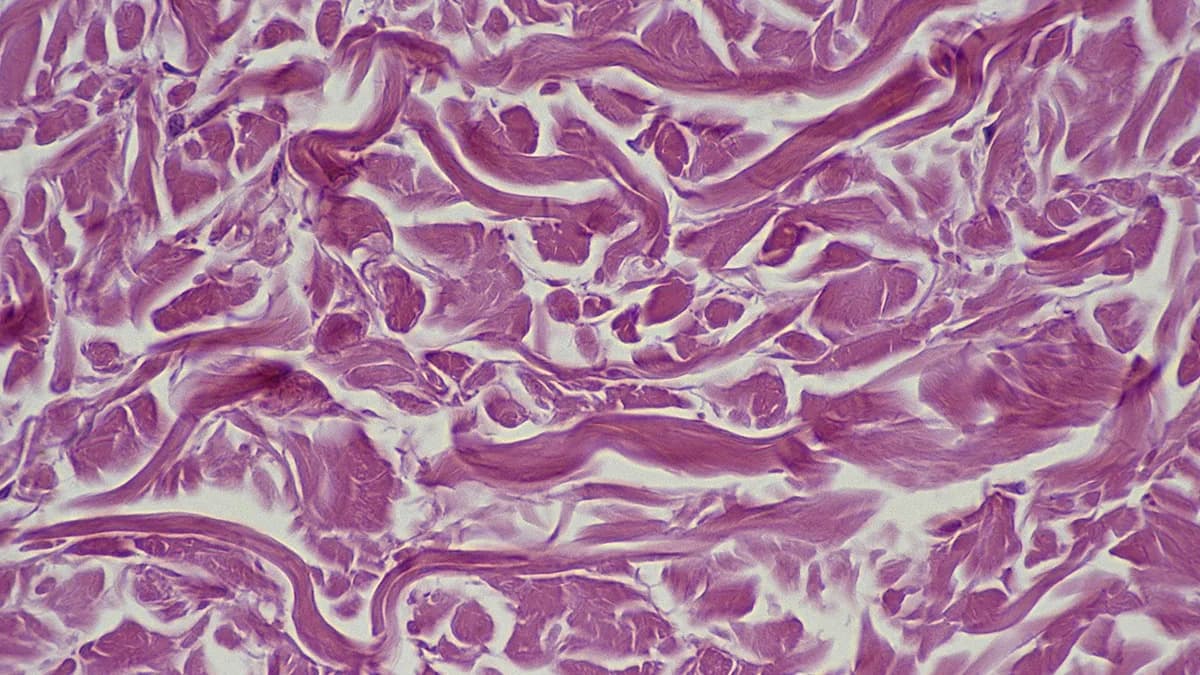

The researchers compared transcriptomes—the sets of genes expressed—in burned and unburned skin samples from humans and rats. They then analyzed the sequences of genes that respond to burns to look for accelerated evolutionary change that might indicate positive selection.

What They Found

A subset of burn‑responsive genes showed evidence consistent with accelerated evolution. Most of these genes are involved in wound closure, inflammation and immune responses—processes that directly affect survival and recovery after tissue damage.

Important Caveats

These same genes are also activated by a variety of other tissue injuries, so the authors cannot definitively attribute the signal of selection to fire exposure alone. Alternative selective pressures—such as injuries from tool use, interpersonal violence or other environmental hazards—could also explain the pattern. The list of genes identified is not exhaustive, and further work is needed to validate specific functional changes and their evolutionary timing.

Why This Matters

Beyond the evolutionary question, the authors propose that their analytical framework can help bridge evolutionary biology and medicine. By highlighting genes that evolved differently in humans, the study may help explain why animal burn models sometimes translate poorly to clinical outcomes and could inform future approaches to burn research and therapies.

Bottom line: The study offers a plausible, carefully qualified example of how life by the hearth might have left biological traces—without claiming a definitive causal link between fire and every detected genetic signal.

Help us improve.