Researchers at Imperial College London argue that habitual human exposure to fire left traces in our genome, favoring variants tied to inflammation, immunity and wound closure. These adaptations likely increased survival after frequent, mild burns but carry trade-offs that worsen outcomes in severe thermal injury. Published in BioEssays, the study suggests a culturally driven form of natural selection and may inform burn treatment research and explain limits of animal models.

Fire May Have Shaped Human DNA — How Habitual Fire Use Could Have Driven Genetic Change

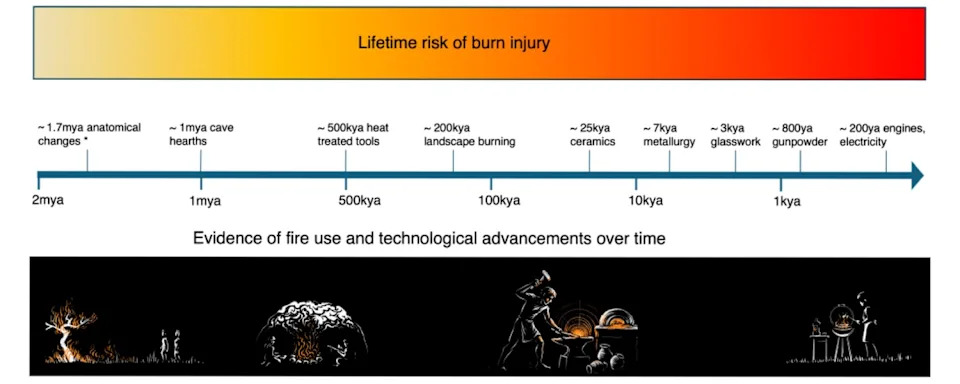

Human control of fire is one of the defining behaviors of our species. New research from Imperial College London argues that the routine exposure to heat and burns over hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of years left detectable marks on the human genome, favoring variants that improve recovery from frequent, mild thermal injuries.

A Cultural Pressure With Biological Consequences

The study, published in BioEssays, compares genomic data across primates and finds that humans carry genetic variants linked to inflammatory and immune responses and to wound-closure processes. The authors propose that these variants were favored by natural selection because they improved survival after the smaller, more frequent burns that accompanied cooking, toolmaking and other fire-related activities.

"Burns are a uniquely human injury. No other species lives alongside high temperatures and the regular risk of burning in the way humans do," said Joshua Cuddihy, co-author and surgeon at Imperial’s Department of Surgery and Cancer.

Why Those Adaptations Matter — And Their Trade-Offs

Burns are classified clinically as first-, second- and third-degree injuries depending on depth and severity. Superficial burns often heal without intervention, while deeper burns destroy skin and underlying tissues and greatly increase the risk of life-threatening bacterial infection. The American Burn Association reports an almost 18% mortality rate among hospitalized burn patients who require surgery and prolonged ventilation.

The genetic changes the researchers highlight would have been especially valuable before modern antibiotics and critical care — increasing survival after repeated, less-severe burns. However, the same rapid inflammatory and repair responses can become harmful after major thermal trauma, contributing to excessive scarring, systemic inflammation and organ failure. That trade-off may explain why humans remain vulnerable to severe burn complications despite apparent evolutionary adaptations.

Implications For Research And Medicine

Beyond shedding light on human evolution, the findings could have practical implications. Understanding how human-specific genetic responses to burns evolved may help researchers design better therapies and could clarify why many burn treatments that work in animal models fail to translate directly to humans.

As co-author and evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi observes, this is "a form of natural selection—one, moreover, that depends on culture." The idea links technological behavior (fire use) to biological evolution and opens new avenues for interdisciplinary study of how culture shapes our biology.

Limitations: The study presents an evolutionary hypothesis based on comparative genomics. While the genomic signals are consistent with selection related to burns, establishing direct causation in human evolutionary history remains challenging and requires further study integrating archaeology, anthropology and functional genomics.

Help us improve.