Researchers led by Joshua Cuddihy compared gene expression in burned and unburned skin from humans and rats and found a subset of burn-response genes evolving faster than expected. These genes are primarily linked to wound closure, inflammation and immune responses. Because the same genes respond to general tissue damage, selection could reflect other human activities as well. The framework may improve burn medicine and explain limits of animal models.

Was the Human Genome Forged by Fire? Study Finds Fast‑Evolving Burn‑Response Genes

Our long relationship with fire is often cited as a defining human trait: we used it to cook food, harden tools, keep warm and deter predators. But could repeated exposure to burns and living around flames have left detectable marks on our DNA?

New research led by Joshua Cuddihy at Imperial College London and published in BioEssays investigates whether genes activated by burn injuries show signs of positive selection in humans.

How the Study Was Done

The team compared transcriptomes—the sets of genes actively expressed—in burned and unburned skin from humans and from rats. By analysing the sequences of genes that respond to burn injury, they searched for a subset showing accelerated evolutionary change compared with background rates.

Key Findings

- A subset of burn-response genes shows evidence of accelerated evolution.

- These genes are mainly involved in wound closure, inflammation, and immune responses that help damaged tissue recover.

Caveats and Alternative Explanations

Importantly, many of the same genes are activated by general tissue damage. That means the observed selection could reflect other recurring pressures in human evolution—such as injuries from tool use, fighting, or other forms of trauma—rather than fire exposure alone. The authors also note that the identified gene set is not exhaustive.

Why It Matters

The study offers a comparative framework that links evolutionary biology with clinical medicine. It could help researchers improve how burn injuries are modelled and treated, and it may explain why animal models of burns sometimes translate poorly to human patients.

Bottom line: There is evidence that some burn-response genes evolved faster than expected, and that our long association with fire is a plausible, though not definitive, contributor to that pattern.

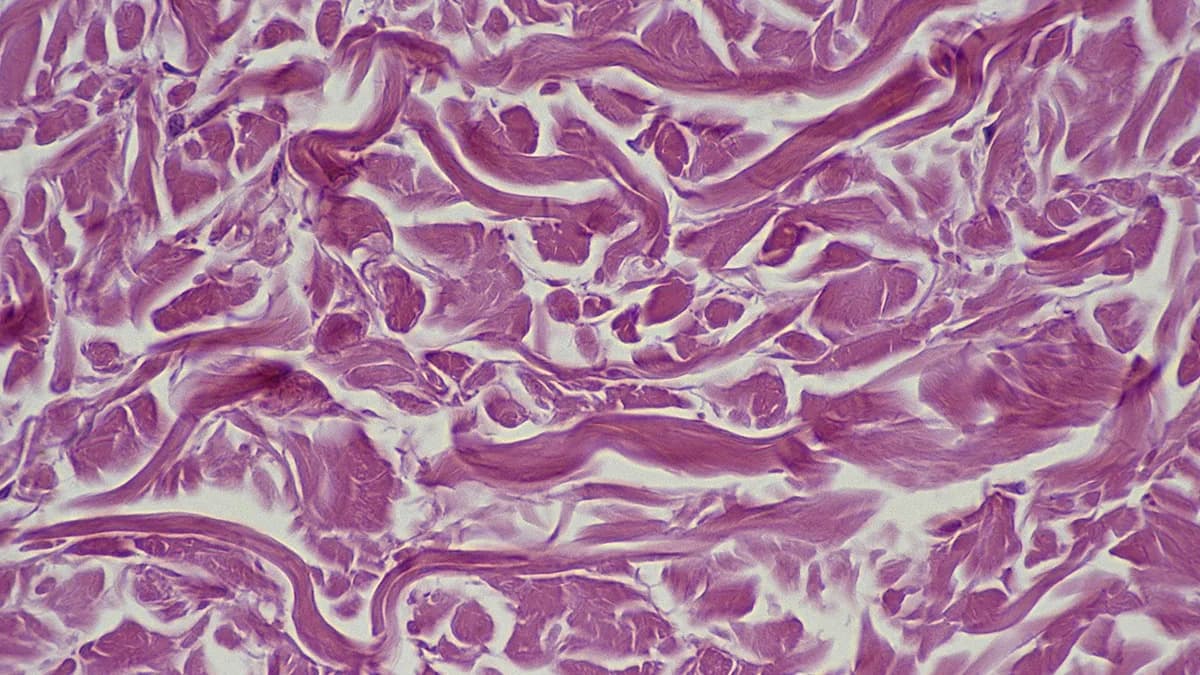

Lead image credit: obsonphoto / Shutterstock. This story was originally featured on Nautilus.

Help us improve.