About 2 billion people suffer from iron deficiency globally. Researchers modified two related genes in rice to boost iron content and used the Canadian Light Source synchrotron to map iron distribution in grains. While iron levels increased, the double-gene change also raised the risk of iron toxicity that can reduce yields in waterlogged soils. The team plans to test the modification in rice grown in aerated soils and in other cereals such as wheat, barley, sorghum and maize to develop safer, iron-rich staple crops.

Enhanced Rice Could Reduce Global Iron Deficiency — Gene Edits Boost Iron But Introduce Risks

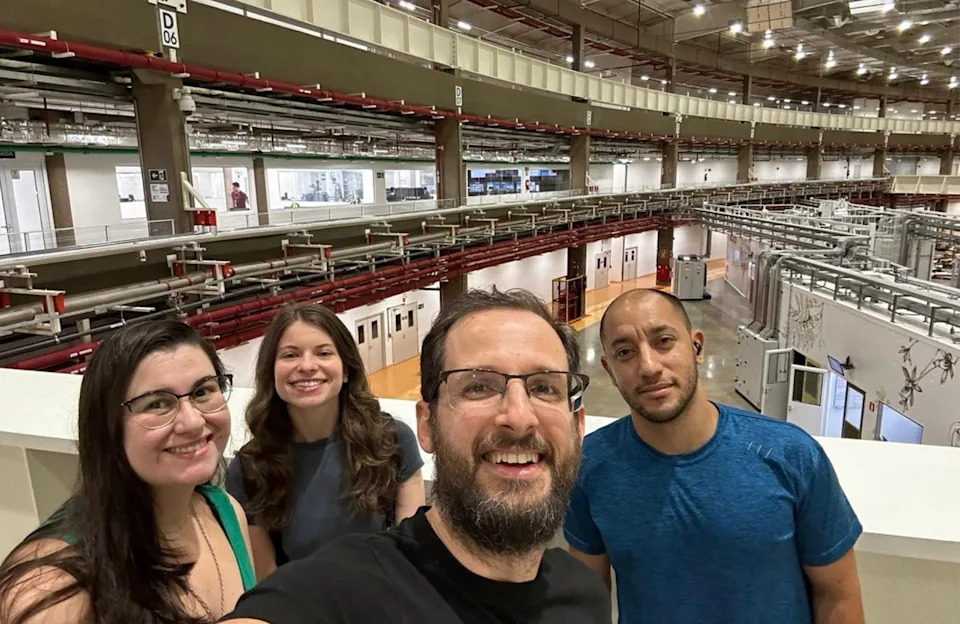

About 2 billion people worldwide suffer from iron deficiency, a condition that can cause illness and even death. Researchers led by Felipe Ricachenevsky, a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, are working to address this problem by increasing the iron content of rice — one of the globe's most widely consumed staple foods.

Why Rice Matters

In some countries, such as Bangladesh, rice provides nearly 80% of daily calories, so boosting iron levels in rice could have a major impact on public health. Previous studies showed that altering a single rice gene can raise iron concentrations in the grain. Building on that work, Ricachenevsky and an international team from Brazil, Italy, Chile and Germany experimented with modifying two related genes in the same plant to see if the effect could be amplified.

How the Research Was Done

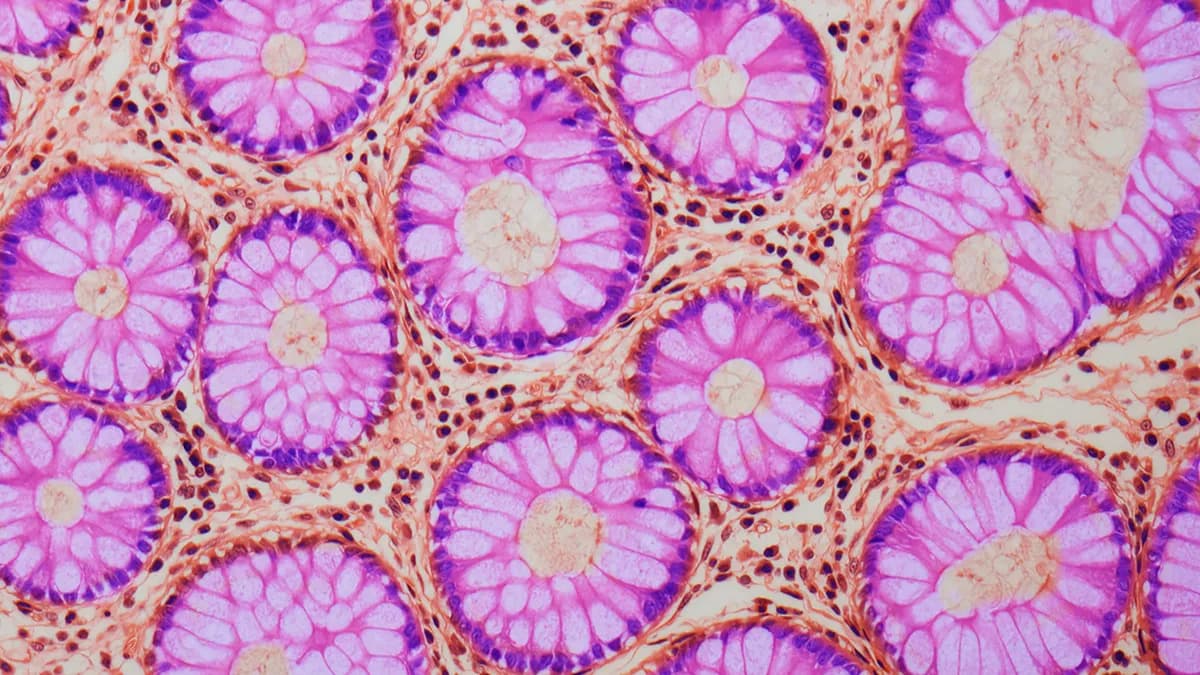

The researchers analyzed their modified plants at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) synchrotron at the University of Saskatchewan. Using bright synchrotron radiation, the team mapped the two-dimensional distribution of iron within individual rice grains, allowing a precise look at where and how much iron accumulated.

Key Findings

The double-gene modification did increase iron concentrations in the rice grain. However, it also made the plants more susceptible to iron toxicity, a condition in which excessive iron uptake damages plant tissues, reduces yields, and can kill crops. Rice grown in shallow, waterlogged fields is particularly vulnerable because iron is more bioavailable in such conditions.

Next Steps and Applications

To reduce the toxicity risk, the team plans to introduce the same genetic changes into rice varieties adapted to aerated (non-waterlogged) soils, where iron is less accessible to roots. They also intend to test the two-gene approach in related cereals that are typically grown in drier soils — including wheat, barley, sorghum and maize — which may be less prone to iron toxicity.

Ricachenevsky and his colleagues hope this strategy will help develop nutrient-dense staple crops that improve iron intake for vulnerable populations worldwide.

Article by Victoria Schramm; submitted courtesy of Canadian Light Source. Originally appeared on AGDAILY.

Help us improve.