Researchers edited two related genes in rice to raise iron concentration in the grain and used synchrotron imaging at the Canadian Light Source to map iron distribution within seeds. The edits successfully increased grain iron but introduced a higher risk of iron toxicity in plants—particularly in waterlogged fields. The team will test the approach in rice varieties grown in aerated soils and in other cereals (wheat, barley, sorghum, maize) to reduce toxicity risk and expand potential benefits.

Gene-Edited Rice Boosts Grain Iron — A Potential Tool Against Global Deficiency

About 2 billion people worldwide suffer from iron deficiency, a condition that can cause illness and even death. Researchers led by Felipe Ricachenevsky, a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, are working to increase iron levels in rice—one of the world's most consumed staple foods—to help address that problem.

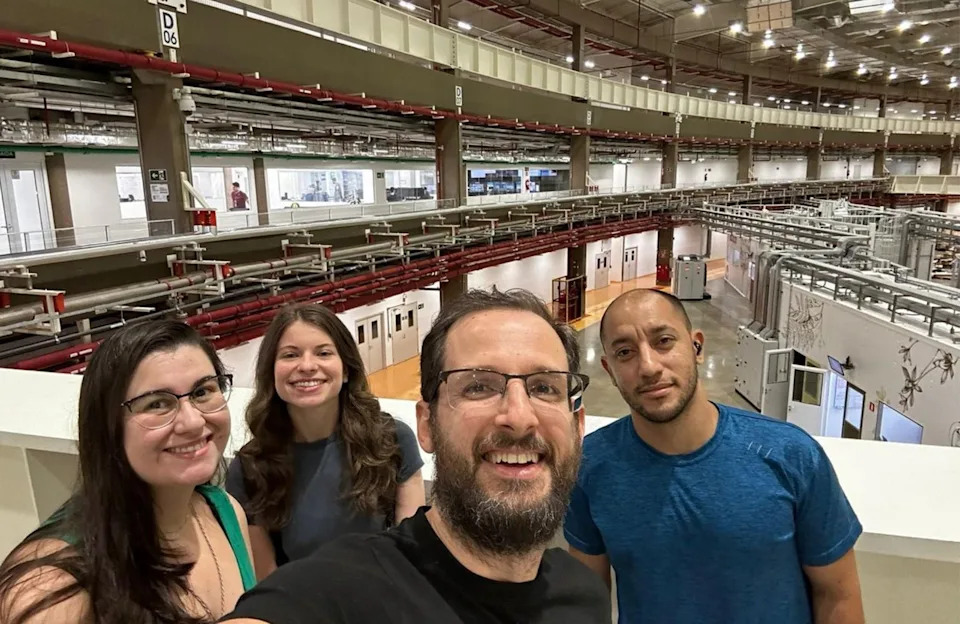

Building on earlier work showing that changing a single gene can raise iron in rice grain, Ricachenevsky and an international team from Brazil, Italy, Chile and Germany edited two related genes in the same plant to try to achieve a larger increase in grain iron.

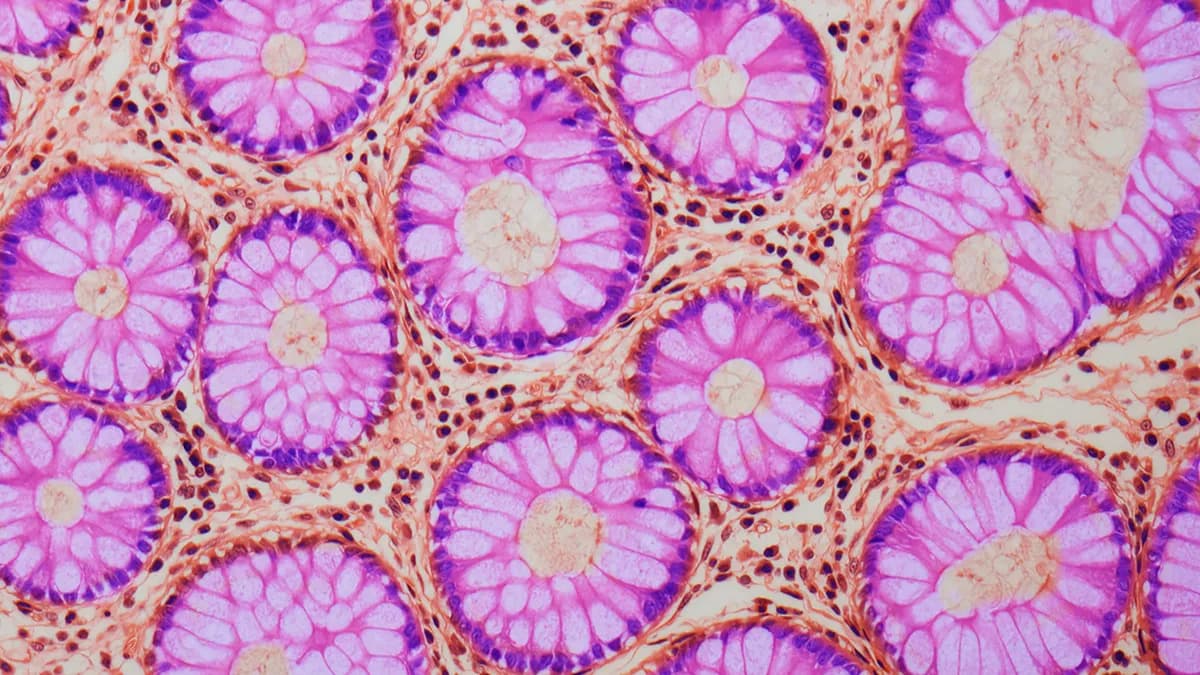

To map how iron was redistributed within the seed, the researchers used the Canadian Light Source (CLS) synchrotron at the University of Saskatchewan. "Using the CLS was a very important step in our research. We used the CLS' bright synchrotron light to see the 2D distribution of iron in the rice grains from our plants," Ricachenevsky said, noting the imaging allowed precise localization of iron within the grain.

The genetic changes did increase iron concentration in the rice grain. However, the double-gene edits also made plants more susceptible to iron toxicity—a condition in which excess iron uptake reduces plant growth and yield and can kill crops. This problem was most pronounced in rice grown in shallow or waterlogged soils, where soluble ferrous iron (Fe2+) is more available to plants.

Next Steps and Broader Applications

The team plans follow-up experiments to address the trade-off between higher grain iron and plant health. Their next steps include introducing the same gene edits into rice varieties cultivated in aerated (well-drained) soils, where iron is less bioavailable and toxicity risk may be lower. The researchers also intend to test the dual-gene modification in other cereal crops that are genetically similar to rice but typically grown in non-waterlogged conditions—such as wheat, barley, sorghum and maize—to determine whether the approach can safely boost iron in a wider set of staple foods.

Ricachenevsky hopes this gene-editing strategy will one day contribute to more nutrient-dense staple crops and reduce iron-deficiency burden in vulnerable populations.

Credits: This article was written by Victoria Schramm and is based on research supported by the Canadian Light Source.

Help us improve.