Roy Plunkett accidentally discovered PTFE (Teflon) in 1938; he patented it in 1941. PTFE’s heat and chemical resistance made it valuable to wartime projects and postwar industry, eventually appearing in cookware, Gore-Tex and many consumer goods. PTFE gave rise to PFAS — persistent “forever chemicals” linked by research to immune, liver and cancer risks — prompting state restrictions, corporate phase-outs and a shift by some consumers away from nonstick pans.

Why Teflon Is Losing Its Luster: From the Manhattan Project to the PFAS Debate

Why Teflon Is Losing Its Luster: The same slippery polymer that made nonstick cookware a kitchen staple also played an unexpected role in the Manhattan Project — and helped launch a family of persistent chemicals now under intense scrutiny.

An Accidental Discovery

Roy Plunkett, a chemist at DuPont, accidentally created polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) in 1938 while developing safer refrigerants. Storing tetrafluoroethylene gas in very cold canisters, Plunkett and technician Jack Rebok one morning found a canister emptied of gas and filled instead with a curious white powder. Tests showed the material was polymerized tetrafluoroethylene — PTFE — notable for extreme heat resistance and remarkable chemical inertness, even against powerful acids.

From Wartime Utility to Consumer Markets

PTFE didn’t enter broad use until the early 1940s. Around 1942, engineers at the Oak Ridge facility in Tennessee — part of the Manhattan Project’s uranium refinement operations — found that corrosive uranium hexafluoride destroyed conventional valve seals and gaskets. PTFE’s durability protected piping and components for decades, and its industrial success helped propel postwar commercialization.

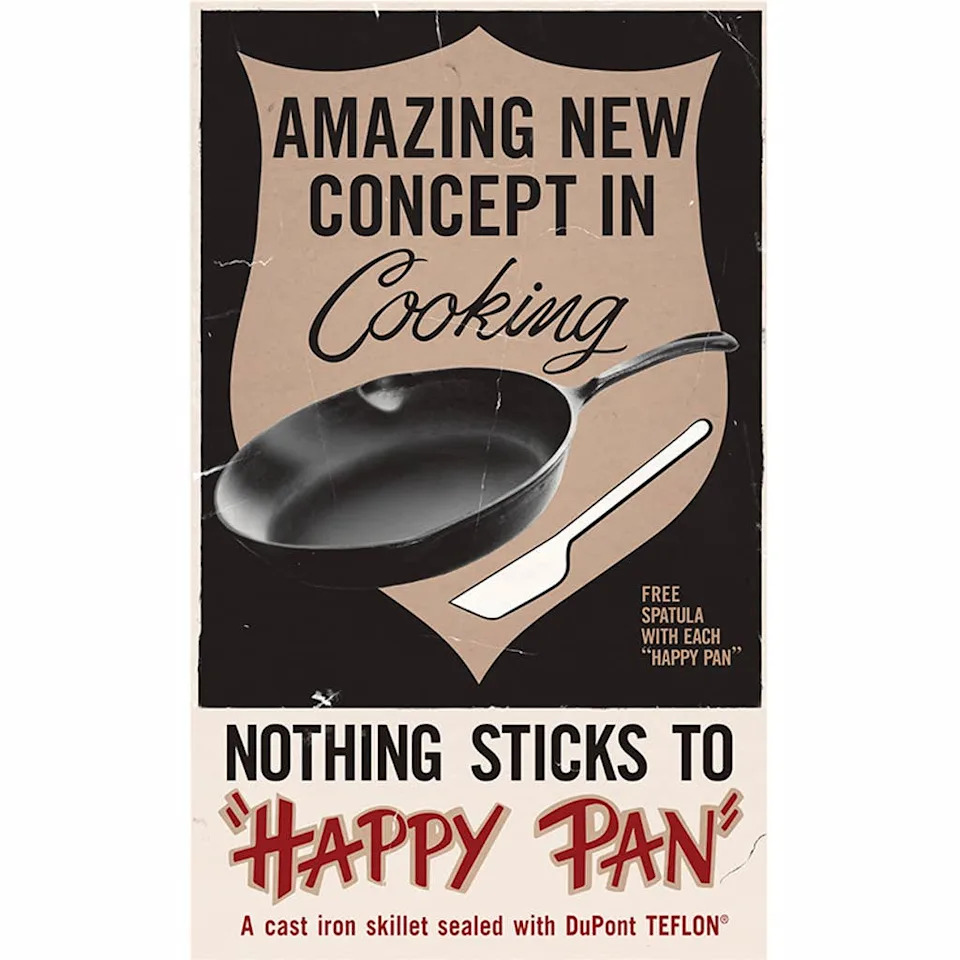

In 1945, the Teflon trademark was registered by Kinetic Chemicals, a DuPont–General Motors venture. Production climbed quickly: Kinetic was soon manufacturing millions of pounds of PTFE annually. By 1961 the first Teflon-coated frying pan, marketed as the Happy Pan, reached U.S. stores. Later in the 1960s, Wilbert and Bob Gore developed a waterproof fabric using a form of PTFE that evolved into Gore-Tex, now common in outdoor apparel. Today PTFE appears in cosmetics, medical devices, kitchenware, furniture and dental products.

PFAS: A Family of “Forever Chemicals”

PTFE’s discovery spawned a broad class of compounds called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Manufacturers prized PFAS because their carbon–fluorine bonds are among the strongest in chemistry, making these chemicals repel water, grease and heat and withstand harsh conditions. That same strength makes PFAS extremely persistent in the environment — earned them the label “forever chemicals.”

PFAS can travel through air, soil, water and food and accumulate in people. Studies detect PFAS in the blood of most Americans and in tissues such as the placenta, brain and lungs.

Health Concerns and Evidence

While definitive causal links for every PFAS-related outcome are still being established, a growing body of research associates PFAS exposure with weakened immune response, higher risks of certain cancers, liver damage and adverse birth outcomes. Scientists continue to investigate mechanisms and specific exposure thresholds.

Policy Responses and Industry Changes

Policy responses have varied. Federal actions have shifted between tightening and relaxing drinking-water limits for PFAS in recent years, while many U.S. states have passed bans or restrictions on PFAS in consumer products. Several manufacturers have voluntarily phased out specific PFAS compounds and developed alternatives.

Consumer Choices

Concerns over PFAS have led some consumers to abandon nonstick pans in favor of stainless steel, cast iron or ceramic cookware. Those alternatives require more maintenance but avoid the potential exposure associated with some fluorinated coatings.

Bottom line: PTFE transformed industries and everyday life, but the durable chemistry that made these materials so useful is also why PFAS persist in the environment and raise health concerns — prompting regulatory scrutiny and changing consumer behavior.

Help us improve.